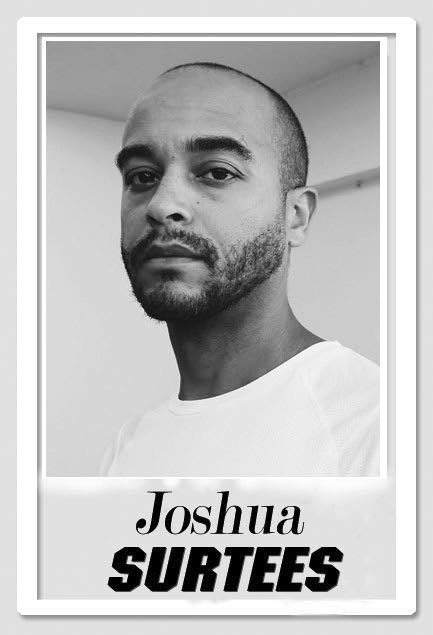

For my grandmother

Two years ago, I wrote my mother’s obituary. I lay beside her as she died in an English coastal town in the middle of winter.

Today I am writing the obituary of her mother, my grandmother, Doris Elsie Surtees. She died on June 14, a month short of her 90th birthday, in a sunlit bedroom looking on to the garden of a beautiful care home in north London, a few hundred yards from my house.

Sadly, I was far away, four days into my honeymoon in a hotel room in Suriname, when I heard the news. I am comforted that before I left, I held her hand and said goodbye for the last time.

I do not believe so much in the idea of being “at peace,” I do not know where the soul goes – or if we even have one – when the body dies. But these past years have taught me that I believe in dying peacefully, and that people deserve a good death. When people have the legal right to choose how they die, I think humanity will have reached a higher plain of civilisation.

My grandmother died peacefully, and for that I am thankful. I am thankful too for the vigil my sister and brother-in-law kept over her in her last weeks and hours – and for the extraordinary love shown to her by her carers.

It was in the leafy affluent borders between Crouch End and Highgate where she spent her final years, after a long, progressive descent into Alzheimer’s. She remained her irrepressible self to the end. Her memory had been robbed by dementia, her wit and intellect stifled by it, but her kind heart, her goodness, her smile, humour, pride and immense strength were still there.

The Victorian house on the tree-lined street where she died is a long way from where she came into this world, in a council house in Bradford, Yorkshire, in the summer of 1928. One of four siblings of the inter-war generation in Britain, she was born to a mother from Lancashire and a father who we now know was born to a well-heeled family in Kingstown, St Vincent, in the British West Indies.

After living through the war, and rationing, and barely attending school because of it all – somehow, she always made wartime Bradford sound rather fun! – she raised three children through the 1950s and 60s and sent them off into the wide world, one as an au pair in Switzerland and Canada, one as a dancer in Cairo, the Bahamas and Paris, one in the merchant navy. The au pair, my mother, went on to be an equestrian, an anthropology graduate, a civil servant and finally a midwife. My grandmother was like a second mother to me and my siblings, helping her give us private schooling, piano lessons and holidays in the South of France.

She never moved with the times, our nan. That was one of the many things we loved about her. Her values, tastes, the way she only ate meat and two veg, the way she laughed until she cried watching Les Dawson on TV, her unabashed kindness, to strangers and friends alike, the way she said: “gee whizz, “by Jove,” and in strong Yorkshire dialect, “eh up!” – all of it came from an age that shaped her and never left her. To me, her middle-class liberal north London grandson, her traditionalism was romantic and strangely exotic.

And yet, she was never truly old fashioned. That she married twice and divorced both husbands with little fuss, spoke of her absolute independence and determination to do things her way. She accepted people for who they were, as long as they were good people. My mother becoming a hippy in the late-1970s, squatting in Camden Town and having three mixed race children with a Jamaican man and then a Nigerian, was a shock to my grandmother’s sensibilities, but she adjusted to it quickly.

Though she was staunchly Yorkshire, our recent discovery that her father was Vincentian and creole (he kept it a secret from his children, friends and family) means that the Caribbean ran through her veins.

In her professional life, she ran an old people’s home in Surrey, England. Devotedly, she nursed many elderly people until they died. Her experience of seeing them grow old and frail made her clear in her convictions that she never wanted to age like that. She told us as much, explicitly and repeatedly. Because of UK law, we could not grant my nan her wish: the right to die a swift, timely death, though it was her sincere and long-held belief.

Hers was a slow passing from this world, and in the absence of a will to choose, she chose stoicism to her last. It gave us a long time to say goodbye and to celebrate her wonderful life.

Comments

"For my grandmother"