Telling the story, again

LISA ALLEN-AGOSTINI

“I AM the daughter of Ricky Assing and Marlene Ballantyne. The sister of Che. I am the granddaughter of John Assing and Mary Verna (born Medina), also Thaddaus Ballantyne and Veronica (born Amoroso). John Assing was the son of Thompson Assing and Clemencia (born Hill) and Mary was the daughter of Ambrosia Medina and Marie Lopez. This is what I remember off the top of my head. This is the way I was taught to introduce myself. It was a way of saying that I never walked alone.” (Excerpt from Unaccounted For, by Tracy Assing, published in So Many Islands.)

Naming things, naming people, naming places, shapes history. How does Kairi become Trinidad? How do the descendants of the First Peoples of this space come to be categorised as Carib, bear Spanish-sounding names like Amoroso and Medina and Lopez, and belong to the Santa Rosa community?

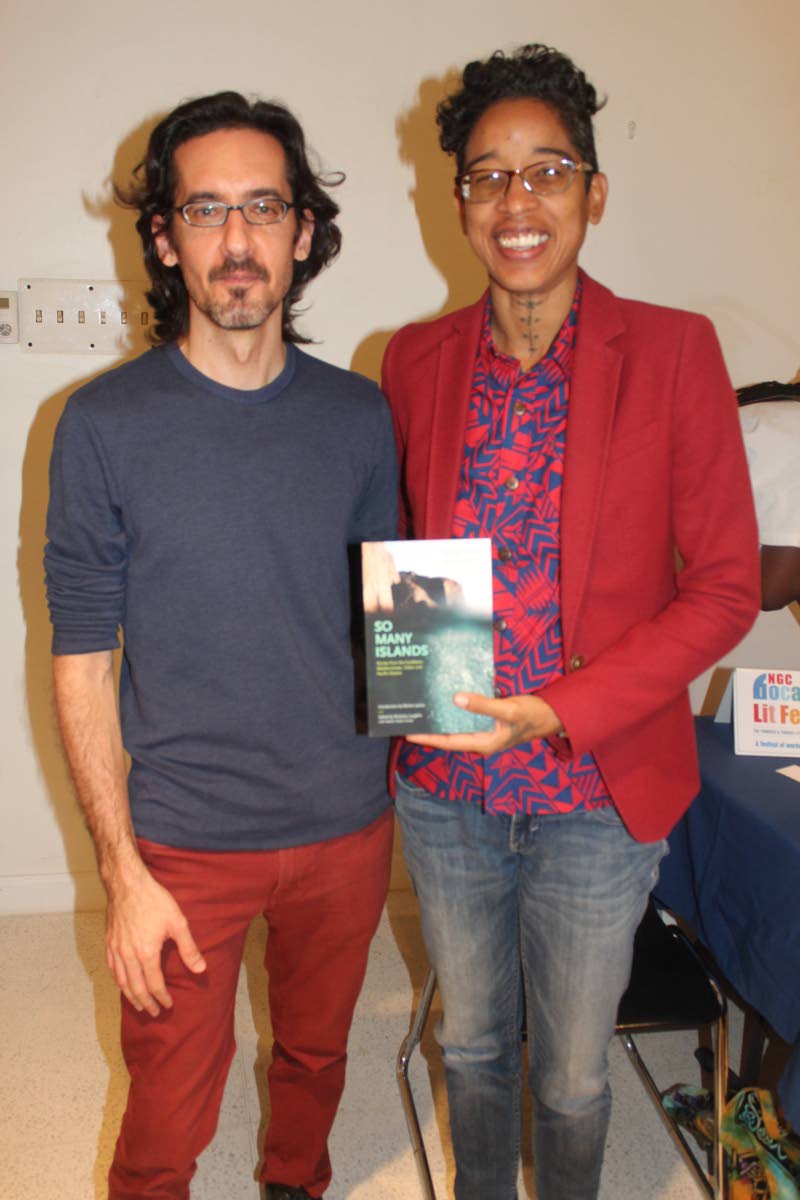

Writer and indigenous Trinidadian Tracy Assing draws on these issues in her essay Unaccounted For, which is the only piece of writing from TT to be included in the new international anthology So Many Islands.

Published in TT by Peekash Press and edited by Nicholas Laughlin with Nailah Folami Imoja, the anthology collects writing about islands in the Commonwealth. Assing’s essay sits alongside poems and stories from Fiji, Samoa, Malta, Kiribati, Singapore, Antigua, Jamaica and Barbados.

Assing, 42, travelled to the South Pacific last year for the launch of the Pacific edition of the book. (There are two other editions, simultaneously published in the Pacific by Little Island Press and the UK by Telegram Books).

Assing said in a Newsday interview late in January, “The similarities (between South Pacific islands and Trinidad) are immediate. The landscape, the vegetation is the same. All the crotons, all the hibiscus, all the breadfruit, all the dasheen, those things are all there. Even with me, because in terms of bone structure or skin tone, even some mannerisms, there are lots of similarities.”

(The slender Assing added, “We were kind of making this joke about how, if creation started there, indigenous people just got smaller and smaller as they moved away from that start island.”)

Her essay, she found, equally resonated with those islands. The essay is a meditation on loss, in one sense—our indigenous people’s struggle for recognition, for equitable and sustainable access to national resources, for human rights.

It is also a celebration of her family heritage.

She writes of her father, “He was barely into his teens when he started hanging out at labour meetings and discussing Marxist-Socialist ideology with a few of the men who would go on to form the National Union of Freedom Fighters (NUFF) in the 1970s. His knowledge of the trails through the Northern Range became indispensable to the guerrillas.”

She draws vivid pictures of his revolutionary work, as well as his relationship with the land.

In the interview she said, “Dad has a habit of making lists of things. You would find scraps of paper around the house with a small headline saying, ‘List of animals’ and he would start a list there. Or he would jot thoughts down, things he remembered. There was always this data lying around the house.

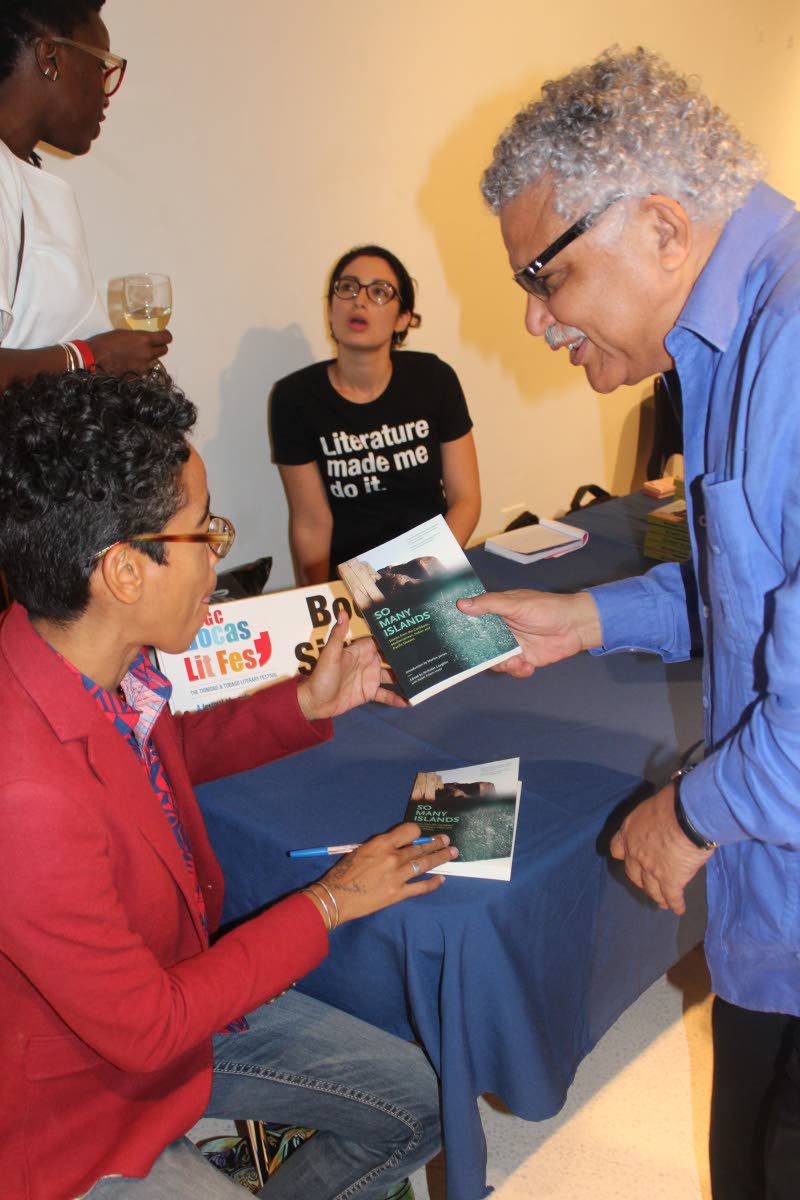

“I was thinking I may have plagiarised some of his lists,” she said, half in jest. Indeed, there was a lilting music to the lists that stood out when she read from the essay at the book’s TT launch, January 17, at Medulla Art Gallery, Woodbrook. Her excerpt started with a story of the tragic legend of Kairi, in which people’s greed was their downfall.

“I started to look at that legend one Carnival, preparing for a festival – just as the legend says the tribe was preparing for the festival and they thought, ‘Oh, these hummingbird feathers look amazing! My costume is going to be lit. I just have to kill a few hummingbirds and get their feathers. It’s going to be resplendent. It’s going to play in the sunshine. It’s going to be amazing.’”

In the legend the people are punished when the Pitch Lake swallows their village.

“It’s overconsumption. And greed. One would also argue obsession with the self. I felt this is what we’ve become; this is Carnival.”

The very pitch bears a lesson for Assing, one she notes in the essay: “Indigenous land rights and the direct relationship between those rights and mineral extraction have long been debated in North and South America. Unfortunately, these issues have never had a place in national discussions in Trinidad and Tobago.”

In the interview she said, “We have been paving roads for some time just laying asphalt on asphalt on asphalt and sometimes the road would be so high and the drain way [below it]. There was no engineering. It was just wasteful. ‘We have a pitch lake so we go use it. Forget the science behind it to make it stay longer. We have it, we ent have to worry.’

“And we have this attitude towards almost everything the land has given us. So the lesson in the legend is that ultimately it leads to destruction, that one can get swallowed up by one’s consumption.

“And now that I’ve been able to take the story to the other side of the world I recognise that it resonates everywhere. That people are being affected by their own greed.”

Assing has become a voice for the First Peoples of Trinidad over her career, which started in journalism. “When I came to town in my 20s – I literally just came from Arima – my motto then, as it is now, was, ‘Infiltrate, informate and repatriate.’ Go in, get the information, learn everything you can and take it back to enrich your community.” She systematically mastered print, radio and TV journalism here and abroad.

“So I kind of moved through with the consciousness that I was trying to learn as I went along and also trying to get this story of indigenous survival in and told over time.

If you look at my back catalogue, articles in the Guardian, in Caribbean Beat, some would argue news stories for 96.1 WEFM, I was always trying to find a way to get that community story out there.”

The work she’s done includes the 2010 documentary film The Amerindians and an entry in Reid and Gilmore’s 2014 Encyclopedia of Caribbean Archaeology.

Assing noted in the interview, “I didn’t study history, but I got to put an entry in an encyclopedia. My ancestors have been praying for this, for some truth to be told, for some story to come out of their existence, for some writing of the information that is still out there.”

Comments

"Telling the story, again"