Tobago’s stony corals threatened

Our corals are the canaries in the coalmine of climate change. Dr Anjani Ganase is warning of the disease that can wipe out our impressive boulder brain corals.

Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) is officially in the Southern Caribbean. Curaçao, Bonaire, Venezuela and even Grenada have reported outbreaks. It is only a matter of time until SCTLD reaches Trinidad and Tobago, and we are not ready.

SCTLD was first recorded in Grenada in 2015, with many confirmed sightings in 2018 and 2019. Bonaire and Venezuela made observations at the end of 2022, and Curaçao at the beginning of 2023.

Within a single year, many of the reefs of Bonaire and Curaçao have suffered mass die-off of their precious brain corals. The rate of mortality is much higher than any previous disease outbreak encountered on Caribbean corals.

White-band disease killed over 80 per cent of the Acropora corals (two species) found throughout the Caribbean within a decade. Acropora corals still have not recovered to date.

SCTLD is likely to exceed this. It targets and can kill over 20 susceptible species, most of which are brain coral, but extends to other massive species, such as the great star coral, and the pillar coral.

First Florida

SCTLD is caused by an unknown pathogen, although there is some consideration that it may be a type of bacterium. After ten years of investigations, scientists continue to be baffled by the disease-causing agent.

This is not unusual, as many coral disease pathogens continue to be unidentified.

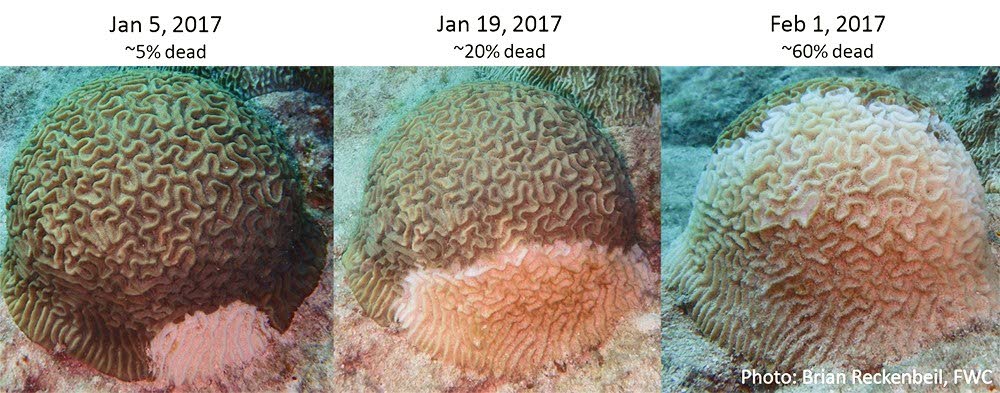

As its name suggests, once infection happens, it results in the formation of lesions in the tissue of the corals which expand very quickly until the lesions get so big that they fuse together, eating away all the tissue of the coral colony, killing it.

The process of infection is quick; it results in death in a matter of weeks or months. By comparison, corals suffering from black band or yellow band disease might take months to years to die.

SCTLD was first discovered in Florida in 2014. Today more than 96,000 acres of the Florida reef tract (over 50 per cent) have been devastated by the disease (30 per cent mortality) and about 45 species of corals have been infected.

In Curaçao, the disease has infected 22 species of corals within its first year of infection. Smaller colonies were killed in a matter of weeks to months, while larger colonies took longer simply because there was more tissue to infect. The spread started from the ports and by 2023 reached the two tips of the island – East Point and West Point – where the more pristine and remote reefs are located.

It only takes a handful of coral colonies to be infected on a reef to result in widespread outbreak. It was estimated that Curaçao will lose 25 per cent of its live coral cover in the coming years (Carmabi Foundation, Curaçao).

Now Tobago

The big concern for Tobago is that most of the reefs are made up of brain coral species, which is highly vulnerable to the disease.

Furthermore, Tobago has a much smaller diversity of corals compared to neighbouring islands. Tobago is home to about 42 species of hard corals, most of which are vulnerable to the disease.

This includes the boulder brain coral, which is the species that has grown to be the well-known “largest brain coral in the Western Hemisphere,” at Speyside. This brain coral alone is a major attraction to our diving tourism. There are several enormous brain coral colonies that cover the reefs of northeast Tobago. Unique dive sites, such as Melville Drift, known for its brain coral dominance, could face complete wipe out with detrimental consequences to the marine fauna.

If there is a SCTLD outbreak, we can expect the mass die-off on our reefs in a couple of years, as was observed in the rest of the Caribbean.

Loss of brain corals that are over 100 years old is something that cannot be repaired in our lifetime. It will signal a dangerous tipping-point for reefs with respect to their viability, limiting their ability for ecological functions as a habitat and food provider, not to mention services provided to the tourism industry.

The main form of spread is through the transport and exchange of ballast water as vessels – cruise liners and cargo ships – move between islands. In many places, the disease often spreads out from reefs near ports.

However, ocean currents are also likely media for transport as well. Nevertheless, management of the ballast-water treatment and exchange on ships should be implemented.

At small scales, scientists have seen some success with the use of a broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment, but the quantity and scale of effort are unrealistic when dealing with outbreaks on a kilometre scale, with thousands of susceptible coral colonies. The antibiotic treatment is not widely available and can be very costly.

Finally, all efforts can be lost anyway if there is not a regular cycle of re-treatment, since the disease can re-infect corals once the treatment is complete. Such treatments should be reserved for our big-boulder brain corals in the northeast of Tobago, given their cultural and ecological importance.

Interventions

Scuba divers and free divers should not dive on infected sites. We need them to report sightings of disease, and they must disinfect gear after diving an infected site.

Of course, they should avoid moving between infected and non-infected sites and touching sick colonies, as the disease spreads through direct contact and through contaminated water.

Management of chronic issues that occur in reef fisheries and water quality is always a must. Declining fish populations on coral reefs have resulted in the concerning trend of eating parrotfish. Parrotfish are critical to coral-reef health and are allies to corals by grazing on algae. Successful management of these issues will be key to safeguarding the future of our reefs.

Unfortunately, the climate is getting warmer. The first outbreak of SCTLD came on the heels of a major heatwave in 2014 that resulted in coral bleaching in the northern Caribbean region. This trend was observed in the 1970s, as a marine heatwave was the likely driver of the devastating white-band disease.

The Caribbean is known as the disease hotspot that is expected to worsen in the future because of climate change.

This year, the Indo-Pacific and Australia are currently experiencing mass coral bleaching, like that the Caribbean experienced at the end of 2023.

As we are officially experiencing another global coral-bleaching event, the fourth one in this decade, we seem to be surpassing climate projections. It is certain that global temperatures are going to overshoot 1.5 C. And the future of coral reefs is uncertain.

Comments

"Tobago’s stony corals threatened"