Good marks for cane

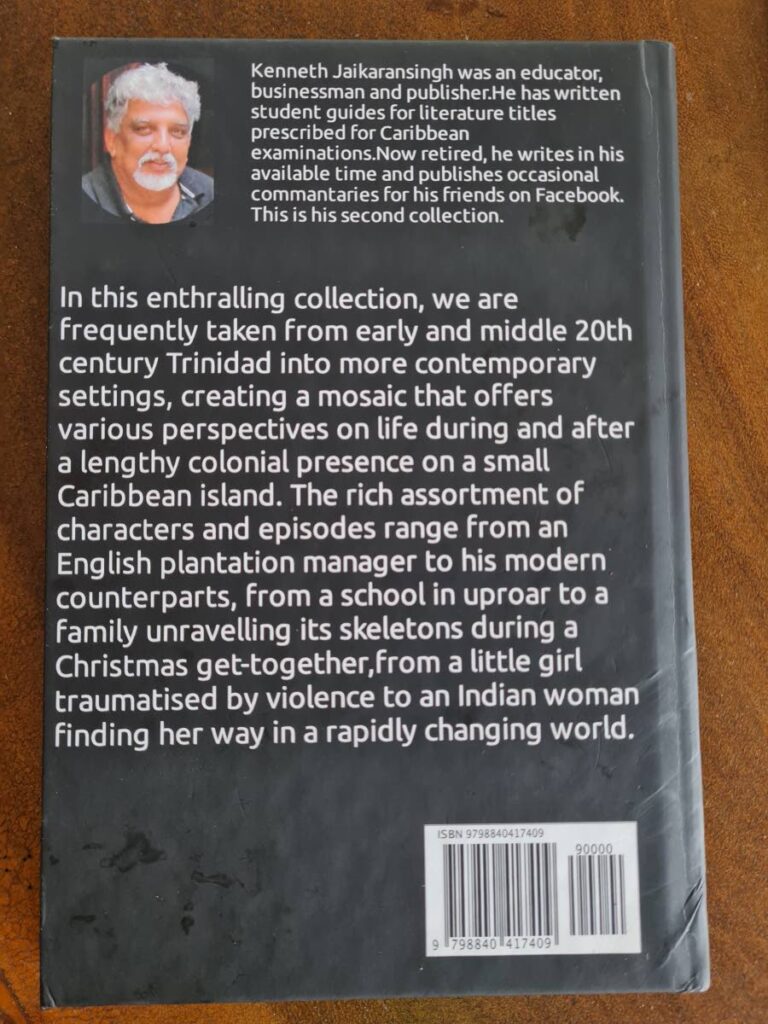

IT’S A cliche that you should never judge a book by its cover. But you could safely do that with the second short-story collection by Ken Jaikaransingh, an educator, publisher and businessman who, in retirement, has turned his substantial writing gift to the art of the short story.

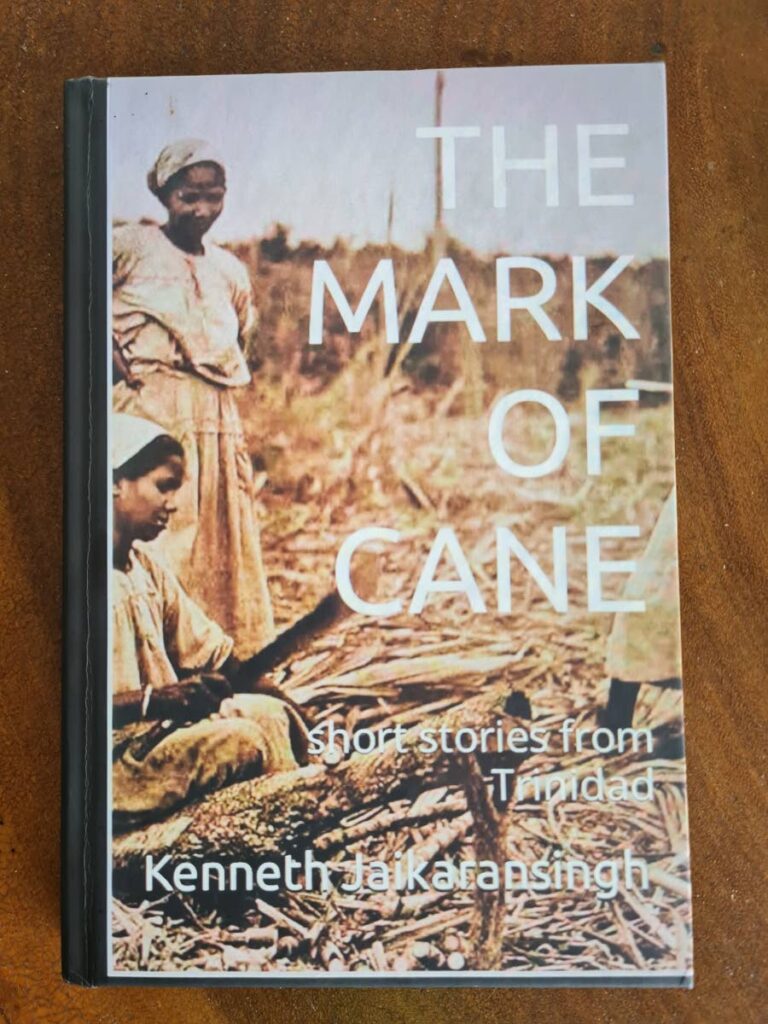

The book you hold in your hand as reader is a thing of beauty: hard-covered, the front cover edged in black, the back cover all-black with its blurb in white text and a glamorous colour photo of the author to crown it all. It is solid and hefty and physically promises substance in the stories within.

In our scandalously ethics-free modern commercial world, where the cheapest version of everything is sold at the most exorbitant price possible to consumers, Jaikaransingh’s book reminds the reader of the tactile delight of actually holding something lovely, such as a well-made book, or the Lord of the Rings Extended Version DVD boxed sets, or a perfectly balanced handmade pool cue. You don’t get a lot of these things any more.

Even the title of the collection – The Mark of Cane – is admirably clever. It plays on the mark of Cain, the first murderer of the God of Abraham, and the stigma in Trinidad of agricultural work, because a lot of the characters populating Jaikaransingh’s stories are descendants of indentured labourers.

The Mark of Cane comprises nine short stories literally bookended by a prologue and an epilogue. These 11 pieces cover an astonishing range of creative writing set in early and middle 20th-century Trinidad.

Jaikaransingh’s first proper job as a young man was as an English teacher at St Mary’s College, his – and my – alma mater. (He taught me, I want to believe, both English and French in form two; and he, and his younger brother, a French teacher at CIC, revelled in the schoolboy nicknames of Zadig and Bligny, the names of the two fictional brothers who starred in our French textbook.)

Jaikaransingh’s ambition in writing these stories is great, and he is largely successful. The stories would have benefited from an editor disciplined enough to remove tautology, however beautifully written, but that is relatively small beer when the stories are as varied and as good as they all are.

The Mark of Cane reads as though Jaikaransingh set out to prove he could himself deftly handle all the techniques he might have taught over the years. (Even after leaving formal teaching, he wrote study guides for secondary-school students.) Tea and Roses, the story that constitutes the prologue, is told from the perspective of an elderly Trinidadian woman whose primary identification is that of the English lady, a child of colonialism who ends up facing old age alone – or having to make do with only one coloured day servant – as the sun finally sets on the British Empire.

In The Road to Happy Acres, time shifts back and forward as the protagonist changes gears on the drive to what turns out to be a literal dead end. In A Term of Trial, the longest story in the book, Jaikaransingh relies on the technique pioneered in English literature by Bram Stoker’s Dracula: the events are laid out in a collection of letters written by disparate authors, mainly teachers at a leading Port of Spain school run by Irish priests.

In Inspector Partap Investigates, one of the more droll stories, Jaikaransingh paints a police character immediately recognisable by anyone who has ever reported anything stolen to a police station in Trinidad – and been required to give, as required by the Summary Offences Act, a description of themselves to the satisfaction of the police officer taking the report!

In Pastelles for Christmas, Jaikaransingh uses the traditional method of preparation of the Hispanic Christmas dish to explore family dynamics that are at once entirely Trinidadian and completely universal.

All the other stories are deserving of individual mention for their particular strengths, but they are done so well that the lucky reader is the one who discovers them through reading them.

It is perhaps the greatest reflection of Jaikaransingh’s talent that, as the stories progress, building on themselves to the epilogue (in which the writer himself finally emerges as his own invented character), more and more links between the stories, the work behind them and the author himself emerge, to the discerning reader’s delight.

If there is a grade for The Mark of Cane, it is an A+.

Comments

"Good marks for cane"