NJAC reflects on February 1970 Black Power revolution

EMBAU MOHENI

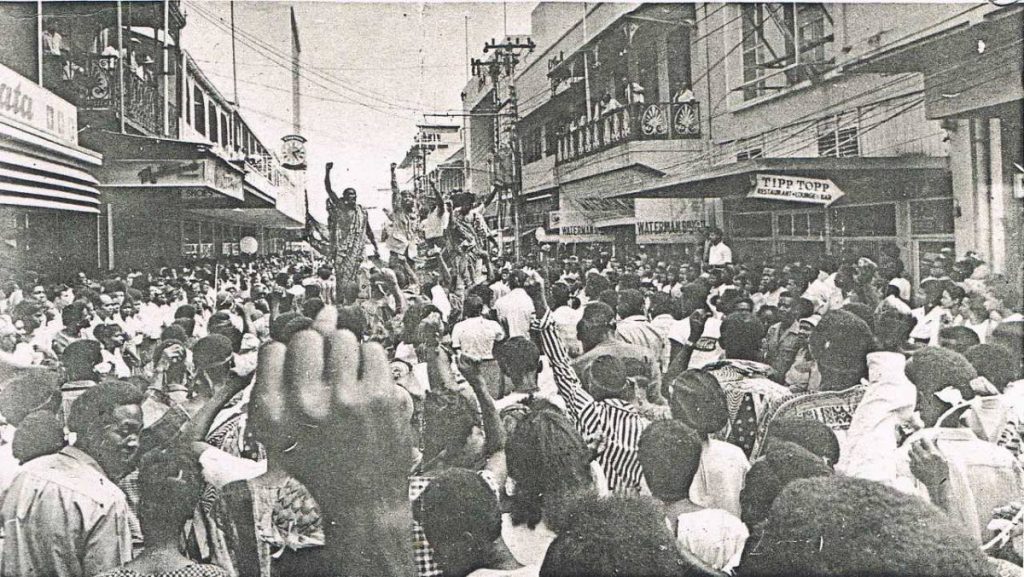

FIFTY-ONE years ago, on February 26, 1970, a mass "people’s movement" for national transformation was launched under the leadership of chief servant Makandal Daaga (then Geddes Granger) and NJAC. The movement has been called the February Revolution, the Black Power Movement and the Trinidad & Tobago Revolution of 1970.

With the rallying cry of “power to the people” sweeping across the nation in mass demonstrations in north, south, east and west Trinidad, and in Tobago, the masses demanded their human right to a meaningful say in the shaping of their future and that of their children.

Six days after the first demonstration of February 26, NJAC introduced TT’s first-ever "people's parliament" on the March 7, 1970, at Woodford Square, (renamed the People’s Parliament three days later), Port of Spain. The concept of democracy in TT was given a new perspective and taken to a new level as people’s parliaments sprang up in various communities across both Trinidad and Tobago.

The people’s parliament is an institution of governance, opened to the public, and which gives the right to one and all to participate, on an equal basis, in the making of decisions related to the nation or community. One of the very significant resolutions coming out of the people’s parliaments was passed at the "parliament" in the Couva car park on March 12, 1970.

For the first time, the “voice of the people,” which is said to be “the voice of God,” was given respect and due consideration. The result was the release of the true spirit, genius and energies of our people, as the population awakened to the opportunity of making TT a beacon of light in the Caribbean.

From a social standpoint, the transformation was unparalleled. Africans and Indians began to forge a new unity for national development, as the respect for people’s humanity took precedence over racial and ethnic differences.

Today, our nation seems to be at a loss in coming to grips with a runaway crime situation. Yet, since 1970 NJAC has displayed its capacity to deal with this burning issue. NJAC replaced the colonial policy of “divide and rule” with the principle of “be a brother, be a sister.” The movement was thus able to generate new togetherness, love and happiness resulting in a 56 per cent reduction in the crime rate. But instead of NJAC being applauded for this unequalled achievement, a state of emergency was declared and the NJAC leadership imprisoned for seven months (April 21 to November 20, 1970). As NJAC’s servant political leader, Kwasi Mutema, stated at the anniversary observances at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Port of Spain, one year ago, “A happy people do not commit crime.”

Fifty-one years after 1970 and the benefits of two oil booms, thousands of children are condemned to lives of misery and hopelessness, merely because they were born into the “wrong” home in the “wrong” geographical location. In 1970, NJAC was instilling a system of values and principles which was giving new meaning to life and living.

As Daaga said in 1972, “We want a society whose ideological basis must be man. We do not want a society whose ideological basis is the machine, whose ideological basis is money, whose ideological basis is profit…. We want a society built on the psychological basis of man so the old person who has given his life to the society can be cared for; the child who is coming up will be seen as the fruit of the nation to be nurtured; the man and woman would be provided with food, shelter, education, clothing and employment. And in return we demand of that man that he gives of his best.”

Contrary to the elitist policy handed down from our former colonial masters, and inherited by many of our local leaders, NJAC’s approach of inclusion infused a new love throughout our society, thus bringing out the best in our people.

For the first time in the nation’s history, people’s right to be included was respected, protected and advanced on the basis of their humanity, rather than being determined by their race, wealth, certification, gender or age. NJAC stood firm with a resounding "no" to any form of discrimination or marginalisation. NJAC’s position is reflected in one of our slogans of the 1970s, which stated, “Old and Young, All Belong in the New Society.”

The movement’s vision of inclusiveness, for instance, placed the elderly in a whole new light. Rather than being treated as objects of a bygone era, the elderly were now given due appreciation and celebrated in one of NJAC’s foundation principles for the development of the new society, which is “honour the old”. This principle speaks to that most important quality of gratitude in recognition of the fact that the road we walk today was paved by those who came before us. Our elders were therefore respected for their wisdom and their knowledge of earlier times and the reservoir of experiences they would thus have acquired. There was thus a new appreciation for the special value of the contribution which they could offer to the quality of life in our nation.

The Revolution also sought to restore our women to their true worth and value. This was expressed in another of our principles which tells us, to “respect and elevate the woman.” The women were seen as custodians of our culture, the “living link between the past and the future.”

With NJAC’s principles of “unite the nation” and “old and young, all belong in the new society,” the "philosophy of inclusion” became very prominent within the society.

On the 51st anniversary of February 26, 1970, we need to reflect and be guided by the concepts and principles which prevailed during the 1970s and which positively had an impact on the social, cultural, economic and spiritual life of the nation. We need to employ the Sankofa principle, which teaches us “to stretch our hands back in time to grasp those things of value, while we yet fasten our eyes on the future we must create with unshakable bonds of love and beauty.”

Comments

"NJAC reflects on February 1970 Black Power revolution"