Integrate environmental, economic and social SDG policies

Associate Business Editor Carla Bridglal wraps up her exclusive interview with UN chief economist Elliot Harris,with whom she discussed the future of the Caribbean in the face of climate change, and the region's need to find new sources of energy.

Elliott Harris knew he was on to something when, as an economist working on macroeconomic policy at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), he found part of crafting these frameworks included poverty and social impact analyses and creating safety nets to mitigate negative effects.

At the time, he wasn’t able to articulate just what it was he thought was missing, but, when he was assigned as the IMF’s special representative to the UN in 2008, looking at the issue from a different agency’s perspective gave him clarity.

“One of the experiences I had was participating in a meeting organised by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) about the green economy and the whole principle of that was, yes, we are going to produce the goods and services that people want, but we are going to do it in a way that is sustainable and doesn’t destroy the environment and has socially acceptable outcomes,” Harris, now the UN’s chief economist and assistant secretary general for economic development, told Business Day in a recent interview at his office in the UN Secretariat in New York.

It was a lightbulb moment, he says, because it meant choosing a policy that might seem to be less good if viewed from a purely economic standpoint, but from a social and environmental perspective, would prove more beneficial overall. This, he would later realise, is the fundamental principle of the UN’s flagship project – the sustainable development goals (SDGs).

“This was back in 2008/2009, before we had the SDGs, but that’s exactly what they were about. You take the social and environmental and (consider) them at the same level of the economic, and you integrate all three. And that is what we are trying to do, (although) that unfortunately isn’t the way policy is made. Economic people do their economics and finance, the health people do their health, agriculture people do their agriculture. They are all in the same government working for the same people, but (their ideas) don’t come together – and that is what really excites me about the SDG. It’s logical. It makes sense. Why didn’t we think of it before?"

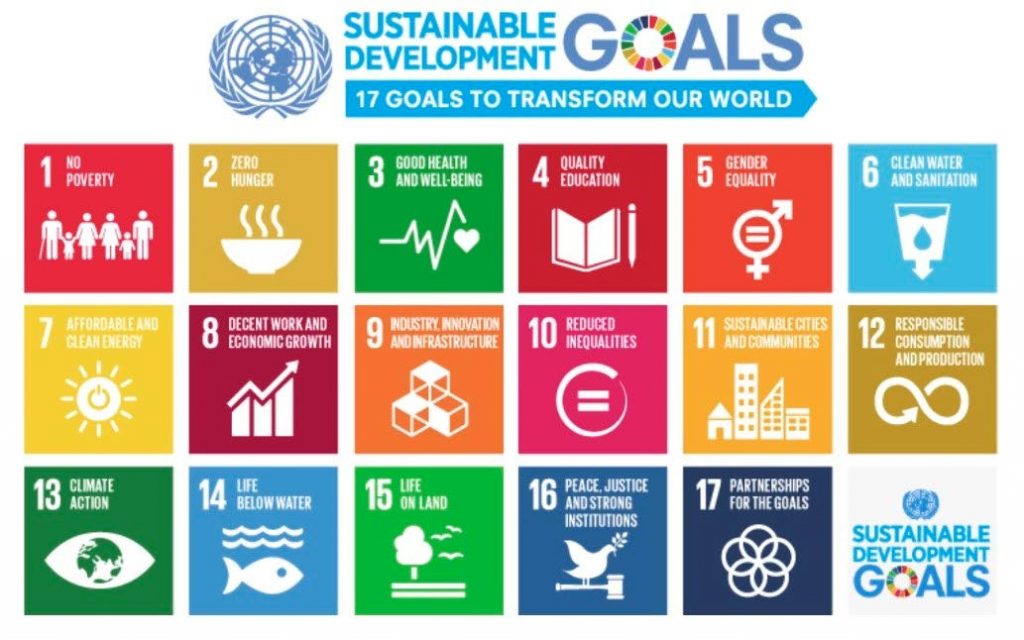

There are 17 sustainable development goals, launched in 2016 by the UN, to replace the millennium development goals (MDGs). The SDGs are a sort of roadmap for UN members to use as their guide to a more sustainable and equitable policy framework to achieve growth and development in a way that benefits all members of society. The UN has set an ambitious timeline of 2030 for countries to meet the SDGs’ targets – if that year sounds familiar, it’s because in TT the SDGs have been adapted to the country’s Vision 2030 strategy.

Harris, 58, a Trinidadian, was part of the team that envisaged and charted the SDGs. He had moved from the IMF to the UNEP.

“It was really interesting, because all the other agencies – I shouldn’t be this blunt about it – the other agencies, they are focused on a particular area. So the World Health Organisation, for example, they had the health goal.

"We at UNEP made a deliberate and conscious decision that we would not advocate for an environment goal. Instead, we wanted the environment to be part of everybody else’s goal. And we were very successful.”

There are 89 out of 169 SDG targets that have an environmental component – half of the agenda – which is exactly what is needed, he said. Environment shouldn’t be a goal off to the side that people could check off to say they had achieved it, but rather, it had to be part of the main goal.

“I think that was a very important innovation. If my business is also your business, then you are going to help me get what I need. For example, we had a joint bit of work together with the WHO called Healthy People, Healthy Planet.

"If you want your people to be healthy you cannot expect them to be healthy if they’re breathing polluted air. So part of your health policy had to be that, you clean up the air.

"But that’s on the environment side. That linkage, then, between what you might do as an environmental-type policy and the impact it has on humans is the motivating factor. We’re not doing it just because it’s an environmental factor: we’re doing it because if we don’t, humans cannot continue to exist on this planet into the future.”

This policy interlink is really a new concept, and, Harris admits, that can make it difficult to implement, but the promise and reward – a planet that is cleaner with resources that can provide for future generations – is huge.

The only future for humanity, then, is a sustainable one. But even though these goals might seem obviously beneficial, there are still some who prefer short-term gratification to long-term viability. And they’re usually politicians trying to make sure they remain relevant until the next election cycle.

“I get a little worried that it’s possible for people to go out there and contort the truth and deny the facts and the reality and still get elected. I find that really worrisome.”

But then, there’s always hope, and sometimes it comes from unexpected sources.

On September 22, a coalition of commercial banks from around the world, representing over US$30 trillion in assets under management, came together at the UN to sign the Principles of Responsible Banking.

This, Harris said, sends a signal that they are committed to lending money in a way that advances the sustainable development agenda, in a way that can influence consumption and production. “Banks finance activity. Imagine if you want to buy a car. If that bank says it will lend you money, but you want to buy a gasoline car, you will have to pay a much higher interest rate on that loan than if you buy a hybrid or electric car, which will you choose?

"That makes a difference in the consumer’s choices and if they (are) asking you to take the more sustainable option and make it cheaper for you to do that, well then, that is going to change the world.”

That these banks based these principles on the SDGs is something that Harris finds “really cool.”

“I find that super-interesting, that commercial banks (and other businesses) can say, look, we can still make money doing things differently…We need now for governments to take heart when they see and (realise that they can) take some decisions that might seem to be dangerous politically and not easily as accepted. They might be surprised to find that people are aware.”

Carla Bridglal is Newsday’s associate business editor. She is one of four 2019 UN Dag Hammarskjöld Journalism Fellows. Over the next two months she will be reporting from the UN in New York.

For the full transcript of Business Day’s interview with Elliott Harris visit www.newsday.co.tt/business

Comments

"Integrate environmental, economic and social SDG policies"