The recipe for stagnation and defeat

When I was a teenager, my mother gave me a book called A Little History of the World by E H Gombrich. At the time, what captured my imagination was the ability to fantasise about historical places and events. Who wouldn’t want to know what it was like to live in the Roman Empire or ancient Carthage, right?

A couple years ago, I picked up the same book and read it again through an entirely new lens; without the idealisation of what were obviously inhumane times that no sane person would want to revisit.

Gombrich tells of the story of the Greco-Persian Wars, starting with the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC and ending with the final Greek victory near Plataea in 479 BC. It was no longer the depiction of the events, but rather the underlying lesson that stayed with me.

Gombrich writes, “this is very interesting, because it wasn’t as if the Persians were weaker or more stupid than the Greeks – far from it…whereas the great empires of the East bound themselves so tightly to the traditions and teachings of their ancestors that they could scarcely move, the Greeks did the opposite. Almost every year they came up with something new…during the hundred years that followed the Persian wars, more went on in the minds of the people of the little city of Athens than in a thousand years in all the great empires of the East.”

Gombrich wasn’t implying that the Greeks were innately better than anyone else; in fact much of what they knew must have been informed by older civilisations. They didn’t, however, allow themselves to be constrained by the dictates of tradition. They dared to deeply question the teachings that were passed down by their parents, grandparents, and other elders. What they ultimately learned, was not what to think, but how to think.

The agora, or gathering place, was the spot in Athens where these public philosophical discussions would occur. And while I can’t imagine people nowadays sitting around discussing the meaning of life in Greek tunics in a public square, the same process of questioning and innovating is at the heart of all progress.

No known creation of humanity has nurtured our advancement more than cities. The agora, of course, could only be made possible by the dense clustering and interaction of different people and activity that happens in cities.

In many ways, informed Trinidadians and Tobagonians of all colours, races, beliefs, and socio-economic statuses lead double lives. Place us in an intellectually open and stimulating environment in the great cities of the world and we will flourish.

When we’re home however, so many of us regress into a primitive state of mind. We somehow forget how to critically analyse and contextualise our own local predicaments, how to connect the dots, and how to seek out new knowledge and question the prevailing ethos. We cheer on the progressive ideas we hear about in other countries, but retreat into our familial conservatism when it comes to home.

Our discourse devolves into the hopeless blame game of the non-thinkers — not directed towards the structures and institutions that cause havoc — of which marginalised group of people is responsible for society’s failings, who’s too lazy to deserve a basic and humane standard of living, or whose behaviour doesn’t conform to traditional and acceptable norms.

Ultimately, without a culture of critical thinking and sense of shared humanity nurtured by a vibrant city — which becomes an agora in and of itself — every problem boils down to us needing a more disciplinarian approach to those errant citizens who don’t behave the way that decency dictates they should. But what is considered decent and acceptable for all in a modern context anyway; bourgeois values?

We are unwilling to do the hard work of digging deeper than what is immediately, but only seemingly, obvious; questioning inherited wisdom; or attempting to understand the underlying environmental and systematic problems that can explain the lawlessness, lack of civic pride, apparently low productivity and work ethic, and so many other challenges.

Our solutions for today rely on a reversion to the comfortable glory days (whatever that means) of a generation or two ago, clinging to teachings and ideologies of religious texts, and simply doing as our all-knowing and apparently infallible elders would have done; all while the country and the world around is on fire figuratively and literally.

I often hear conservative-minded disciplinarians blame all of society’s problems on people’s laziness and delinquency. They have a point. Our problem is laziness, but of the intellectual kind, made possible by the lack of our own agora, and ironically, exactly the reason why the intellectually-dishonest views of these types people are taken seriously.

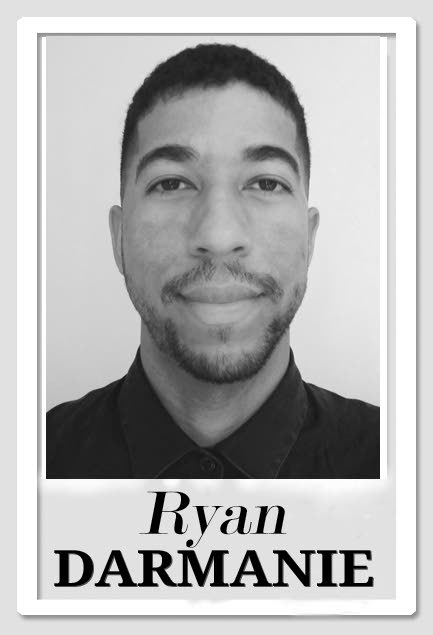

Ryan Darmanie is an urban planning and design consultant with a master’s degree in city and regional planning from Rutgers University, New Jersey, and a keen interest in urban revitalisation. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or email him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"The recipe for stagnation and defeat"