Guyana enters the oil age

KEVIN RAMNARINE

IN FEBRUARY 2017, I captioned an article about the Guyana-Suriname basin, The New North Sea, comparing ExxonMobil’s discoveries in Guyana to discoveries in the Norwegian North Sea starting in 1969.

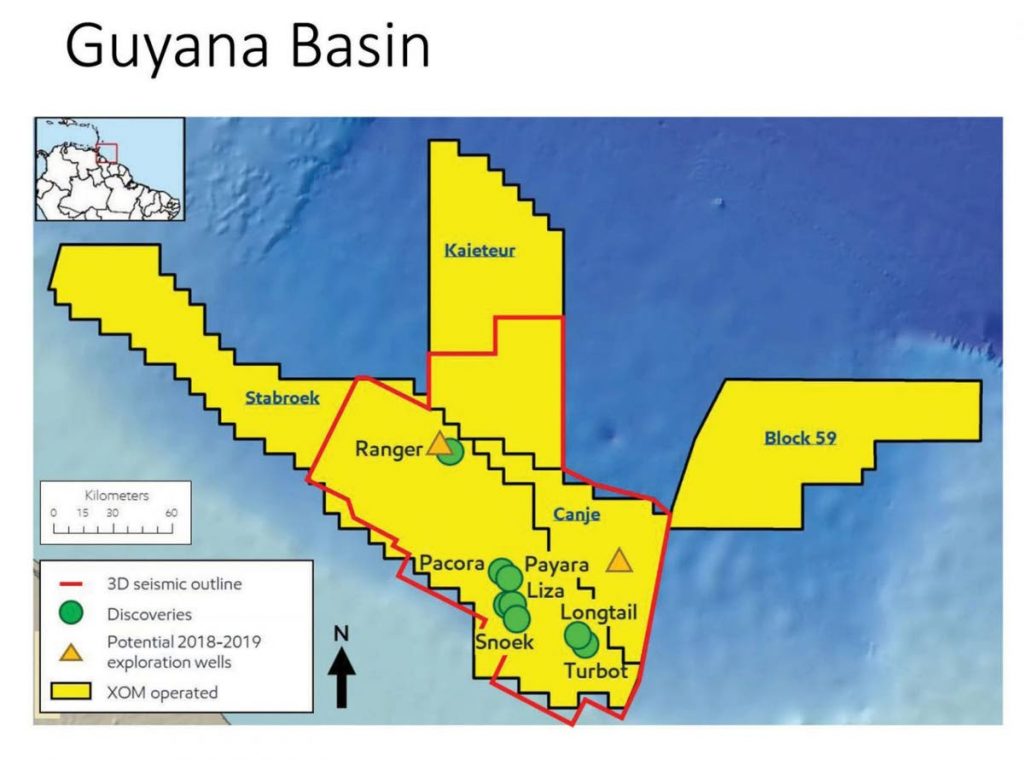

When I wrote that article, ExxonMobil announced its success with the Payara-1 exploration well after two years of drilling in the Liza area, in its 6.6 million-acre Stabroek Block. After Payara-1 came a string of discoveries — 13 in all. ExxonMobil’s most recent estimate for total recoverable reserves is 5.5 billion oil equivalent barrels. Not included are the reserves in some other discoveries that are still being studied. As exploration continues this number will keep growing. More recent discoveries in 2019 like Haimara have been reported as gas condensate-bearing sandstone.

ExxonMobil expects production to reach 750,000 barrels of oil per day by 2025, which would require five floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) vessels. Guyana’s oil production could eclipse the one million barrels per day mark towards the end of the next decade. That level of production would make Guyana one of the biggest oil producers in the world on a per capita basis, placing them in a league with countries that have high levels of production and small populations such as Kuwait, Qatar and Oman. On an absolute basis, Guyana would be producing almost as much oil as the United Kingdom and more oil than larger countries like Colombia and Indonesia.

Assuming an oil price of US$60 per barrel and current projections for oil production from 2020 to 2030, Guyana will realise a revenue stream starting at greater than US$300 million per year in the early years, which will increase to more than US$6 billion per year by 2026. The lower revenue in early years is due to ExxonMobil recovering its capital expenditure outlay using the cost recovery mechanism in its contract. Not surprisingly, Guyana was listed as the fastest growing economy in the world.

In the last four years, Guyana has been inundated with information about the Dutch Disease and Resource Curse thesis. Foreign governments, the multi-laterals, law firms and consultants have all lined up to give advice. It is ultimately up to the Guyanese to sift through all that advice and craft a strategy that suits their unique circumstances.

Of critical importance is the fiscal and regulatory framework that governs this new oil sector. To date there are no new laws in place to govern the sector come first oil in nine months. The government has, however, passed a Sovereign Wealth Fund Bill but even that is mired in political controversy. In late 2017, the government of Guyana made public the production sharing Agreement (PSA) between Guyana and ExxonMobil. The terms of the PSA have attracted criticism and there have been calls for its re-negotiation. Some of the criticism is warranted and some is based on misunderstandings of the agreement. In 2018, Paul Collier, regarded as one of the most influential development economists in the world, said it would be disastrous to "tear up" the PSA with ExxonMobil.

There is also the political stalemate of the last eight months which arises out of the successful December 2018, no-confidence vote against the APNU-AFC coalition. With the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) declaring that the no confidence motion was valid, the stage has been set for early general elections in Guyana. On July 12, the CCJ gave its consequential orders regarding its ruling on the validity of the no confidence motion. In a nutshell, the CCJ referred the government of Guyana back to section 106 of the constitution, which spells out what should happen following a successful motion of no confidence. The CCJ expressed the view that the incumbent government will continue as a “caretaker” and be restrained in its use of legal authority. A protracted political stalemate does not augur well for Guyana.

The uncertainty has, however, not impeded plans by the oil companies. ExxonMobil is undaunted and is moving forward with plans for first oil from its Liza development in early 2020 and plans for the Liza Phase 2 development are well in train. Added to that, Tullow just started its first exploration well Jethro Lobe in the Orinduik Block. In September, Spanish giant Repsol will drill its first exploration well in the Kanuku Block. It will be good for Guyana that its offshore acreage has multiple players as opposed to a single dominant operator. There are also plans to explore the Kaieteur and Canje Blocks where ExxonMobil is the operator. In late 2019, it is also expected that CGX, a long-standing explorer of Guyana, and its new partner Fronterra will drill the Utakwaaka-1 well in the Corentyne Block.

The country has an infrastructure deficit that needs to be addressed if it is to develop its capacity to support the oil industry and its capacity to build its manufacturing, mining and services sectors. Given the mobility of labour and capital in the Caricom region it is likely that Guyana’s impending boom will draw these resources from other countries. With the rapid convergence of early general elections and the coming of “first oil,” the stage is set for a most interesting next nine months in Guyana. Whatever happens, the oil will flow, and Guyana will have entered an oil epoch.

* The writer is a former energy minister and international energy consultant.

Comments

"Guyana enters the oil age"