Canadian museum acquires C’bean images

THERE are over 3,500 images in the Montgomery Collection of Caribbean Photographs – in Canada. These images, photographs, postcards, daguerreotypes, lantern slides, albums and stereographs will now be held at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), Toronto and will be exhibited in 2021.

A June 9 Jamaica Observer article said Toronto’s black and Caribbean communities raised more than Can$300,000 to bring the collection to AGO.

A June 6 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) article detailing how the collection came into existence said New York-based photography collector Patrick Montgomery, whose vacations in the Caribbean always included visits to local historical societies and museums, was surprised at how few of them had photography collections.

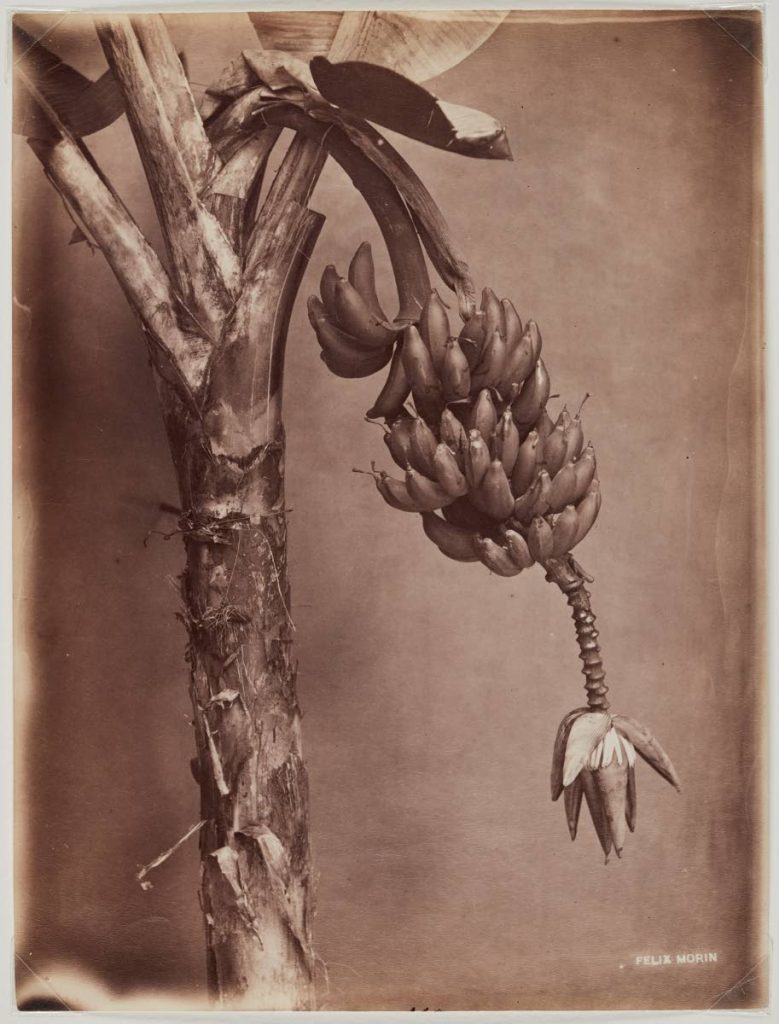

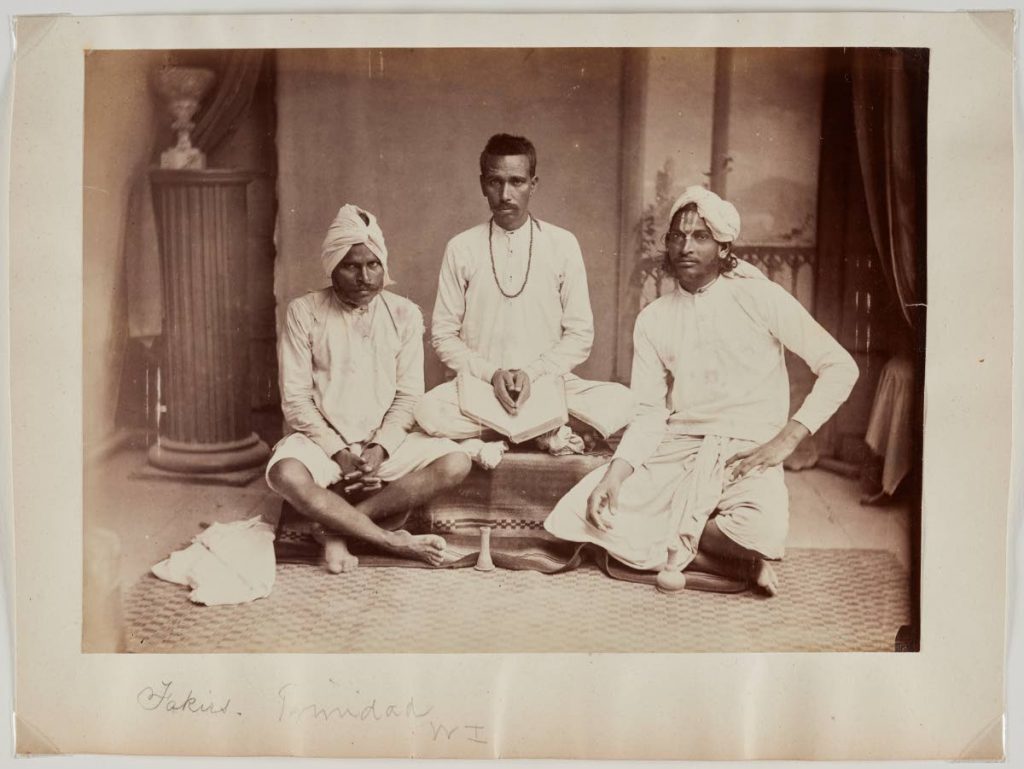

Gift of Patrick Montgomery, 2019

It added that this curiosity led Montgomery to search for historical photos taken in the Caribbean and so in 2005 “he started contacting photo dealers and scanning online auction catalogues to see what he could find." The items show life in Caribbean islands such as Trinidad, Jamaica and Barbados between 1840 and 1940.

It turned out, the article added, that those images and items showing life in the Caribbean as it was then did exist, but "just not in the Caribbean." Montgomery's decade-long search took him to France and the UK where a lot of photos from the former colonies ended up.

Julie Crooks, the AGO’s assistant curator of photography, in a phone interview with Newsday, said the collection reflects the region from around the 1840s to the 1940s.

Crooks said the AGO came across the collection in New York City and she and her colleague Sophie Hackett (AGO’s curator of photography) went to see the collection along with Montgomery. They realised, “It was really a very special and rich collection that focuses on the period and is reflective of the heterogeneous make-up of different regions in the Caribbean.”

Crooks added that the collection features images from other Caribbean islands like Martinique, the Bahamas, St Vincent, Grenada, Bermuda, Nevis, Curacao, Saba and Cuba, as well as mainland countries such as Belize, Colombia and Venezuela.

“It has a very wide reach in terms of representing the wider Caribbean region,” Crooks added.

She said the collection is significant not only because of its size, content, subject matter and historical moments, but also significant to the large Caribbean demographic in Toronto.

The Caribbean histories, she said, were embedded in the “Canadian landscape” by the “significant waves of Caribbean immigrants to Toronto.” The Caribbean diaspora, Crooks said, had made significant contributions to Canada, “Starting in the 1910s and then more significantly in the 50s and 60s and that diaspora have made significant contributions to Canada. So those histories are embedded in the Canadian landscape and it puts the Caribbean in a very global context.” This was why the collection was important to the AGO.

While the collection tells “all of these different stories that all of these communities tend to relate to and see themselves when they come into the AGO” and “scholars can dig deeper into those histories,” Crooks said it was important to have it “embedded” in the AGO’s collection, since “it is also telling a story that is a Canadian story,” because of the history of immigration.

At the AGO, historically, Crooks said, there had not been a relationship with the Caribbean community in this way, and acquiring the collection “was a way of cultivating the patronage and support and as well as building a sense of self and ownership through this collection.”

Before its 2021 exhibition, the AGO hopes to “really research” the collection, which would open it up for collaborations with regional universities like the University of the West Indies (UWI).

Crooks added that the AGO was also thinking of study days when colleagues from Barbados, TT and Jamaica could come to the AGO “to actually see the objects in person and to lend some of their expertise to the collection and vice versa.” She said there was also opportunity for “cross-pollination/cross-discussion” around the collection and other collections related to the Caribbean.

The news of the collection’s acquisition raised questions about the region’s own ability to acquire and build collections like the Montgomery collection. Crooks said she attended a conference last year in Barbados which spoke about the lack of infrastructure and resources in regional museums to “hold on to some of this material.” She added that sometimes families and estates do not think about bequeathing some of these objects to local government archives, local museums and institutes that “can help to preserve and conserve the objects.” It was important to impress on people how important the material is to telling individual/regional stories and histories, Crooks said. As it relates specifically to TT, Crooks said, there are a lot of images of the Indo-Caribbean.

It is to the AGO’s credit and the people who contributed to the cost of the collection for acquiring the collection, Dr Rita Pemberton, former head of the Department of History at UWI said.

While Toronto’s black community recognised the value of history and historical records, she said, people in TT have not fully recognised “the importance of documentation on the past: written, images, whatever.”

Pemberton recalled when the Prime Minister bought 12 of the 19th-century artist Michel Jean Cazabon’s paintings in 2015, there was much discussion "about the whys and the wherefores and whether the money should have been better spent in other spaces,” which suggested people “have not yet come to recognise the value of historical records.”

Items like the Montgomery collection and Cazabon’s paintings are important, Pemberton said, because “If you do not know your past, you just are going nowhere.” These things were important to push people and their respective communities forward.

“Any of the famous personalities from Nelson Mandela, King (Martin Luther King Jr) anybody, they tell you just that. In Africa, there is imagery of the bird looking back. You have to look back to propel yourself forward,” Pemberton said.

She said Montgomery built the collection based on his own interest in history.

“He was interested in collecting these items and then he came to recognition, which is the sad truth about much of the Caribbean that the images and much of the documentation about the history of the region, exists outside of the region.”

This Pemberton described this as being the “first sad part” of the region’s history.

“If we want to reconstruct any aspect of our history, we have to make the trek to archives in London, France, Spain, Holland and elsewhere. It is costly and beyond the reach of many, so that there are better collections about us than we have ourselves,” she said.

While TT’s National Archives “has made great strides so far,” she was uncertain whether the funding to the institution is adequate “to make it move in the way that it could and should.”

The problem with institutions like the archive will always be funding and how funding is allocated." She asked on what considerations should money be allocated to archiving when people “are going to be out there saying they want more jobs and more salaries.”

But she saw a solution, saying improving on archiving also improved the country’s ability to provide employment. Archiving, she said, assisted in helping people develop particular kinds of skills and things like the Montgomery collection can feed into job and content creation through filmmaking and storytelling. Archiving, paper restoration, curating and museum management were other areas where Pemberton saw people being trained and employed.

As for collecting archives in the first place, “People, not just government or individuals in government, should be on the look-out for the availability of some of these kinds of items. If you are aware and see these things, maybe you can form a small group, just like they did in Toronto, and they decided this was necessary and raised the necessary funds,” Pemberton suggested.

Dr Kim Johnson, researcher and head of the Carnival Institute, shared similar thoughts, saying in TT people did not place a very high value on archives and record-keeping. Working at the Carnival Institute (a research and archiving body, gathering information and artefacts related to Carnival), Johnson said the institute was “so underfunded and under staffed, it is very difficult to do what we are mandated to do.”

The lack of value for historical items and things, Johnson said, was evident in the way an old building is knocked down in TT and a new one put up.

“We don’t care about the past at all and Trinidadians have always been so and it is a very sad thing,” he said.

This was also seen in the state of TT’s museums and lack of preservation and archiving by private bodies that have “huge collections” like newspapers.

“The Guardian burned down in the 80s and we lost everything starting from 1917 to 1980. And that is a collection of photographs and so on.”

Johnson said there are collectors in TT (like the late Angelo Bissessarsingh) who see the importance of collecting and archiving, but these tended be individuals.

The old Trinidad and Tobago Television (TTT), he pointed out, very often did not keep its tapes but recorded over them “so I don’t know what we have of say (Dr) Eric Williams (TT’s first prime minister).”

Johnson sees this as having a very negative impact on TT going forward. TT and the region’s inability to value historical items and not acquire things like the Montgomery collection, he said, “shows our lack of self-respect and our maturity as countries which can take care of our own history.

“Again it shows that we are not up to the task and other people have to do it for us.”

Johnson said it is even more important and tragic in TT’s case because TT had “one of the greatest Caribbean historians as a prime minister for about 30 years.

“We have produced some of the greatest world historians – Eric Williams and CLR James were some of the greatest historians in the world – and for us to still have no respect for our own history and the artefacts of our own history is a very sad thing.”

Preserving history has become even more crucial, he said, because of the current state of technological and environmental change, where “people lose things...things that they grew up with...things of their childhood...”

Globally, Johnson said, people are experiencing a sense of continuous loss of their past.

“The world changes and technology changes and the environment changes...at an increasingly rapid pace. When we allow things to just disappear it creates a sense of loss and nostalgia. Trinidadians are now beginning to feel as if we are rushing into the future and we have no past.”

This, he added, makes people feel almost unmoored and not belonging to a place because “the past no longer exists.” Johnson said this was a very depressing emotional state to be in.

He made the case for preserving and collecting historical item like the Montgomery collection, saying, “When we have these photographs and things that remind us of what we were, it grounds us in our own society.”

Comments

"Canadian museum acquires C’bean images"