Once upon a time…

SHEREEN ALI

Amidst the gritty realities of life, it’s sometimes nice to escape on the brightly coloured wings of a fairy tale or two, immersing ourselves into a world of fantasy to rejuvenate our spirits. There was one session of the Bocas Lit Fest last month dedicated to just that notion: the weird and wonderful world of fairy tales.

Entitled, Why Fairy Tales Still Matter, eminent author and literary critic Marina Warner gave an insightful talk on the origins of the folk tales we call fairy tales, and why they remain vital today.

The May 5 Sunday morning session began with an unexpected song, as High Court judge and poet James Aboud took off his robes to get lyrical, sitting on the front edge of the Nalis AV Room wooden stage to sing the poem Deliverance from his second volume of poetry, Lagahoo Poems (2003, Peepal Tree Press).

Deliverance was a love song by a lagahoo to a married woman. Lagahoo is the Trinidad version of the shape-shifter, the creole word derived from the French loup-garoux or werewolf. Accompanied by Noel Amming strumming on guitar, Aboud crooned: “It was she who called me to their bed, her bare limbs wet and glistening / Deliverance my love…”, playing the part of a mysterious, somewhat sinister lagahoo who visits a woman in bed for undisclosed exchanges, his presence totally unknown by a sleeping, oblivious husband.

Warner, professor of English and Creative Writing at Birkbeck College, UK, then took the podium to delve into the meanings of fairy tales.

“When I first started writing about fairy tales, they were considered a disparaged form of old wives’s tales. Plato even refers to such nonsense as trivialities that old women pass on to addle and confuse the minds of the young,” she began.

“It was Angela Carter who gave us permission (to value fairy tales) with her great collection in 1979 of The Bloody Chamber, in which she revisited a lot of the classics of the nursery such as Sleeping Beauty and Beauty and the Beast. She revolutionized them in a way that opened up their meanings – not just for adults, but also for the idea that you could use this despised, old, childish form to inaugurate new ideas.”

Warner said fairy tales are a form of folkloric memories: “We tend to think of memory as something to do with fact and history or personal experience, but memory is also the imaginative reservoir of our dreams and fantasies over time.”

The very first written record of Cinderella is ninth century Chinese; but that version already shows the storyteller’s awareness that the audience had previously heard it, Warner explained. “That’s a very important aspect of fairy tales: it’s a bond between people... The stories are familiar.”

“So even if we don’t know who the lagahoo is, we recognize the idea of the succubus, this creature who comes in the night, and also the idea of deliverance – often these ideas are ideas of resistance… a reservoir of energy and defiance.”

She defined a fairy tale as a short traditional spoken tale with elements of the supernatural, thought to be aimed at children, but also written for adults.

The supernatural in fairy tales differs from the supernatural in faith or religion, said Warner, in that a fairy tale does not demand your belief or your obedience. Now, a fairy tale may command your belief – “there are definitely people who believe in fairies, and there are people who believe in zombies and ghosts” said Warner – but the quality of the belief does not belong to an institution, like a religion, that will impose that belief on you, she said.

“For that reason, the kinds of enchantments you read about in fairy tales give you a certain freedom. You can dissent, you can enjoy it, you can thrill to it. I mean, I don’t believe a (magical) lover will come in the night, even to deliver me, but I really enjoy the thrill of that thought,” she commented, alluding to Aboud’s lagahoo poem.

“And there’s also a way that those hauntings from the past, from the collective memory of the stories, can be a deliverance,” she said, noting that fairy tales are symbolic ways of certain kinds of thinking about where we are, and how we relate, and what might happen. They transport us far way in fantastical stories to let us think about things in a safe way, or to give warnings of dangers, or to encourage or inspire us with hope. They pass on the accumulated wisdom of the tribe in symbolic or subliminal ways.

Original fairy tale art Perrault/Red Riding Hood, far left, and Donkey-Skin, far right, are both by Russian illustrator Nadezhda Illarionova. The Douen image is from a mas costume by TT artist Tracey Sankar. Collage by S Ali.

A lot of the wonderful stories of fairy tales are about the resistance to injustice and the return of equilibrium, said Warner. So there are many stories in which the tyrant is overthrown, or the tyrant is a cannibal who wants to eat children, and the children trick the cannibal into not doing that.

And there are many, many stories about sex, she said. Those stories, such as Beauty and the Beast or Bluebeard, have different solutions to the problems, tensions and violence at the centre of sexual relationships, and have ways to re-imagine them and even escape from them, said Warner.

Importantly, fairy tales are where you hear about women’s experience very closely, no matter what the culture, said Warner. “What we are hearing are generational memories of what children were told in the past, often by grannies or nursemaids.”

“One of the greatest collection of stories that has percolated into cultures all over the world is The Arabian Nights,” noted Warner. The figure of Scheherazade tells stories in bed – a nocturnal, secret, confidential setting – to her husband-tyrant who is killing every woman he marries the night after he deflowers them, because he thinks all women are treacherous. So Scheherazade survives through a brilliant device: every night, she tells him a story with a cliff-hanger just before dawn breaks, when the king must leave to go to work. He must return the next night to hear what happens. So her slaughter is kept at bay.

“This idea that you save yourself by telling stories – that the story is the path to salvation – lies very deep in the function of this kind of storytelling,” said Warner. “It mobilizes symbolic language, familiar plots, it mobilizes fears and terrors and hopes and desires, all towards the end of either preparing the child for the experience of the world, or deflecting these dangers and these horrors by the resource of imagination and the defiance often of humour and entertainment.”

Despite their happy endings, Warner said the heart of many fairy tales is torment and pain. “There’s this ghastliness that is being wrestled with,” she said. This can include themes such as people preying on children, violence against women, the murder of innocents, and many other dark and monstrous things that people do to each other. So Bluebeard, in the stories, kills his wives, or the ogre eats his children, or Sleeping Beauty’s stepmother-in-law decides to boil her grandchildren in a pot. The end of the tales are often simply a promise of reprieve, or a kind of defiance, said Warner.

Image courtesy Dan Welldon Photography

Warner briefly retold Charles Perrault’s tale The Donkey Skin, which is a variation of a Cinderella-type story. In The Donkey Skin, the beautiful wife of a great king dies. On her deathbed, the queen makes her husband promise that he will not marry anyone else unless she is as good and beautiful as the dying queen. So the king swears to do that. Though he looks far and wide, he cannot find a lady to live up to his departed wife. But as the years pass and his daughter grows up, he notices she is becoming as beautiful, good and charming as her mother was, and he decides to marry her.

Afraid of not being obedient to her father’s wishes, the girl asks her father to first give her a dress in the colours of the sky. He does so. Then she asks him for a dress capturing the shimmer of the moon. He does so. Then she asks him for a dress in all the radiance of the sun. He delivers on all three near-impossible tasks. The daughter finally asks for the skin of a donkey, which her father gives to her. Late one night, she puts on the donkey skin over her body and runs away from home. She goes from riches to rags, working in menial cleaning jobs in different villages disguised as an ugly woman in a donkey skin, deliberately making herself unattractive and unrecognisable.

At night, though, in secret, she cleans herself up and puts on her beautiful dresses to remind herself of how beautiful she really is beneath all the disguises. Then by accident, a prince sees her true beauty through a window one night, he falls in love with her, they get married, and all ends happily ever after.

“This is a story about incest,” said Warner, “but it is completely displaced into this long ago and faraway place. My belief is that this is a very powerful way of communicating the basic laws of a society – for example, that a father should not marry his daughter… This is a very good way of passing on the knowledge of the community, the actual order that we need to live by, the prohibitions we must observe; but not doing it in such a way that it terrifies people.

“Psychologist Adam Philips once wrote that the closer the bogeyman is to the man next door, the more terrified the children are. Children understand about the bogeyman. But you don’t want them to think that it’s the man next door, necessarily”, said Warner, making the point that fairy tales are deliberately told to be entertaining and not threatening. This means that the villains and monsters are portrayed as living in a world far away, a different, magical word from the one we live in, a made-up world where we can indirectly (and safely) confront some difficult things.

Today, fairy tales are much more than a literary medium, noted Warner: they are also oral, visual, dramatic, dance, and even digital forms of fairy tale in a world now swept by multimedia. The internet especially is a rich source of many new experiments in sharing the communal, ever-evolving memory of shared culture and folk wisdom that is the essence of fairy tales, she said.

And there is an increasing blurring of the lines between genres of folk tale, fairy tale, fantasy and science fiction, which often these days borrow from each other, said Warner. The 2006 dark fantasy film Pan’s Labyrinth, for instance, written and directed by Guillermo del Toro, is a contemporary melange of folk, fairy and myth, she said.

“While the territory of fairy tale is pain, the spirit of fairy tale is defiance,” said Warner. “I think it’s hope inflicted by resistance, by the idea that we’re not going to get done by this. By making a story about it, we’re going to actually overcome it. We’re going to defeat this. We’re going to defeat the ogre.”

About Marina Warner

Marina Warner is an English novelist, short story writer, historian, lecturer and prolific mythographer who has been a visiting professor at many universities. Born in London to an English father and an Italian mother, her paternal grandfather, born in Trinidad, was the English cricketer Sir Pelham “Plum” Warner. Her many books include Alone Of All Her Sex: The Myth And The Cult Of The Virgin Mary (1976), Phantasmagoria (2006), and a literary study of The Arabian Nights called Stranger Magic (2011) which won three prestigious awards.

Warner has a lifelong interest in the role of myth and folklore and was head judge of this year’s OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature. Warner most recently received lifetime achievement awards from the British Academy (2017) and the World Fantasy Convention (2017).

Of mermaids, douens and churiles

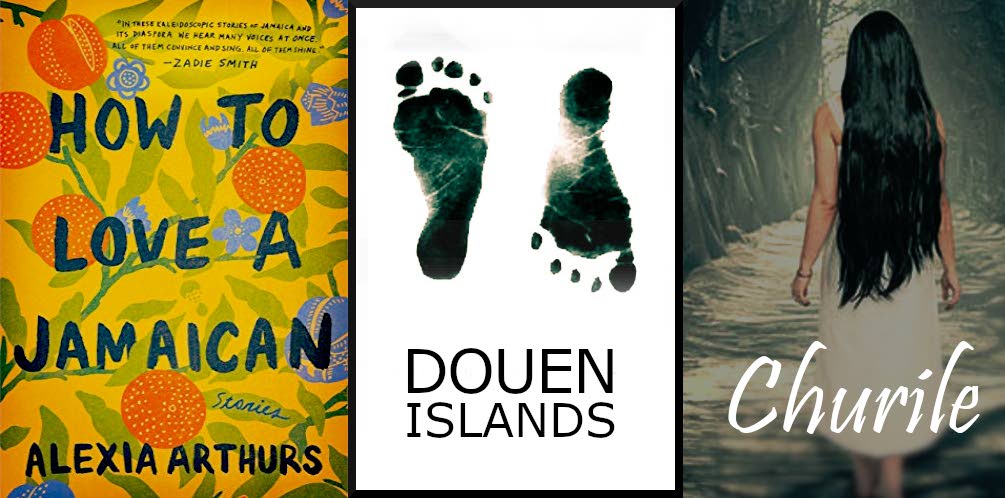

Three Caribbean writers told some tall tales to a keen audience at the recent Bocas Lit Fest session on “Why Fairy Tales Matter.” Jamaican writer Alexia Arthurs read from her mermaid-influenced story Slack, taken from her successful 2018 book How to Love a Jamaican. TT poet and journalist Andre Bagoo read his eerie short story Night Class, where shadowy hints of douens (unbaptised, ungendered, faceless ghost children who eat water crabs) cross paths with a lone security guard on night duty. And Vashti Bolah read from a story about a “churile”, which is the spirit of a pregnant woman who has died during or shortly after childbirth and who haunts the living. Her story was taken from her new book Sugar Cane Valley – Stories of East Indian Folklore and Superstition.

Comments

"Once upon a time…"