The year of living delicately

BitDepth#1294

BETWEEN March 2020 and March 2021, we all went to school. As with so many educational experiences I've had, it wasn't a course I'd have willingly signed up with foreknowledge of what I was getting into, but that doesn't invalidate the things experienced.

We learned to stay home

There was something surreal about the country in March and April of 2020, a sense of an entire country holding its breath, waiting, but afraid to exhale. The streets were either spookily empty or thinly populated with pedestrians and vehicles.

Toss in vines and wild grass and some streets might have served as sets for a dystopian drama, the faces seen in distant windows, a grim portent underlining the surreal quiet, punctuated by the Doppler whoosh of a car passing by.

I'd been working out of a home office for a decade and half by that point, but even then it wasn't easy.

We learned how to be virtual

The essentials of human connection were dramatically reconfigured as conversations were conducted over VOIP tools like Zoom, and the tiny rectangles of webcams turned us all into The Brady Bunch.

From the perspective of a journalist, being able to attend multiple events via recordings and to fast-forward through the fluffy bits was a bitter cross-trade for the viscera of in-person cross-examination.

We learned who we were, really

The best memes at the onset of pandemic isolation were the ones with Jack Nicholson in The Shining. "Isolated with the family," they suggested cheerily, "what could go wrong?"

I don't recall taking an axe to any doors, though I might be misremembering some moments of frustrated anger, but Stanley Kubrick's remorselessly eerie interpretation of Stephen King's book as a lockdown descent into madness wasn't far off for some. That kind of sustained proximity can be revealing, and we weren't ready for what it revealed.

We learned about sudden, inexplicable loss

After years of spotty interaction with my classmates at Trinity College in Moka, we planned a meet-up in 2019, 50 years after our arrival at the school. I hadn't seen Nigel and David for four decades, but there they were sitting next to each other chatting in a video clip I'd shot at the informal dinner, then standing, shoulder to shoulder, in a group photo the next day at the college.

Nigel was taken by covid19 early in the outbreak, his last contribution to our class WhatsApp group a selfie on a gurney wearing an oxygen mask.

David died months later, after being infected in a New York hospital while undergoing treatment for an unrelated illness.

There is a wispy quality to their loss in my mind, distant memories rekindled briefly, then extinguished forever.

We still don't understand the reality of frontline medical workers

I don't know enough doctors, but I do know one, Rory, a friend who's worked the last few months in frontline care in the parallel healthcare system in Jamaica.

As bad as getting covid19 was for the young doctor – he closely escaped being put on a ventilator – it paled compared to the experience of fighting to resuscitate a colleague and friend felled by post-covid19 myocarditis-induced arrhythmia.

When he woke up, he discovered that five more people had died.

He's watched people die for a lack of ventilators, overseen care in a hospital without oxygen supply as his medical team bagged people with room air.

"There is a cavalier attitude towards the virus in the Caribbean," he wrote in our conversation on chat. "Even patients on the verge of respiratory collapse seem confident of survival."

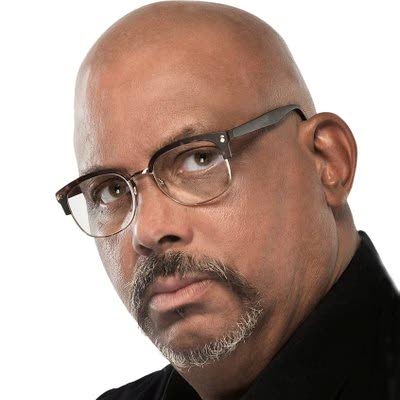

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"The year of living delicately"