Space exhibition explores what portraits mean in local art

There’s a huge range of work – especially for such a tiny show – in the little gallery at Space inna Space. But perhaps the single most striking and intriguing thing about it is its topic: Portraits.

Why should that be unusual? Portraits have been part of art for many centuries. The earliest are from Egyptian tombs dating from 3,000 BC. The word conjures, too, dark-eyed, curly-haired young Alexandrians; Holbein’s guarded, brooding Thomas Cromwell; egg-faced, shaven-browed medieval ladies weighed down by the expensive draperies that displayed their husbands’ wealth; bright-eyed French belles in complicated wigs and diaphanous frocks; more sober 18th-century gents in sheeny frock coats and knee breeches that showed off the turn of a fine calf.

But what of local portraits? There are assorted unnamed exotic figures by Cazabon, but one suspects they are types rather than individuals, and some chosen for their outfits as much as their features. Pallid busts of Sir Louis de Verteuil and Captain Cipriani gaze blankly at MPs in the Red House; a few full-length statues of modern celebrities are dotted around Port of Spain, all best forgotten. There’s the surprisingly modern 19th-century monument to Sir Ralph Woodford in Trinity Cathedral, said to be by the famous sculptor Sir Francis Chantrey but actually designed by Trinidad-based artist Richard Bridgens.

Until they were destroyed in a fire at the Port of Spain town hall, the colony possessed a collection of paintings of assorted governors: Sir Ralph Abercrombie; the infamous Thomas Picton; Lord Harris; Woodford again, by Sir Thomas Lawrence, no less. All gone; even the statue of Harris in his eponymous square was reduced to scrap and last heard of piled in a crocus bag in the keeping of the municipal police.

Since then, it’s generally been assumed that a portrait, whether of someone notable or merely someone with an interesting face, is synonymous with a photograph. The numerous presidents, prime ministers and ministers whose likenesses must scrutinise every public building like watchmen – it goes without saying that these portraits will be photos (though the Central Bank, a shining exception and possessor of a distinguished art collection, commissions paintings of its governors).

As for artists, for the most part they don’t even attempt figure painting or drawing (again, there are exceptions: there’s Che Lovelace and his interest in movement; Chris Cozier and Nikolai Noel are brilliant draughtsmen of the human form; Irenee Shaw is a traditional portraitist).

None of the works in this show, then, are painted or made for the motives that often influenced historical European portraits; they’re not intended to convey the gravitas, importance, wealth or in most cases even the beauty of their subjects. That has changed elsewhere too, of course; portraits are probably now more likely to be done at the artist’s request than commissioned by the sitter, and the social status of the latter is no longer assumed to be above that of the artist, a mere jobbing artisan. Portraits are also more likely to try to be biographical, reflecting the subject’s characters as well as the outward trappings of their public identity and place.

This gallery’s owner, artist Richard Ashraph Ramsaran, likes to give his shows themes and commission the artists, and hence has pulled together a cross-section of what “portraiture” means in TT art.

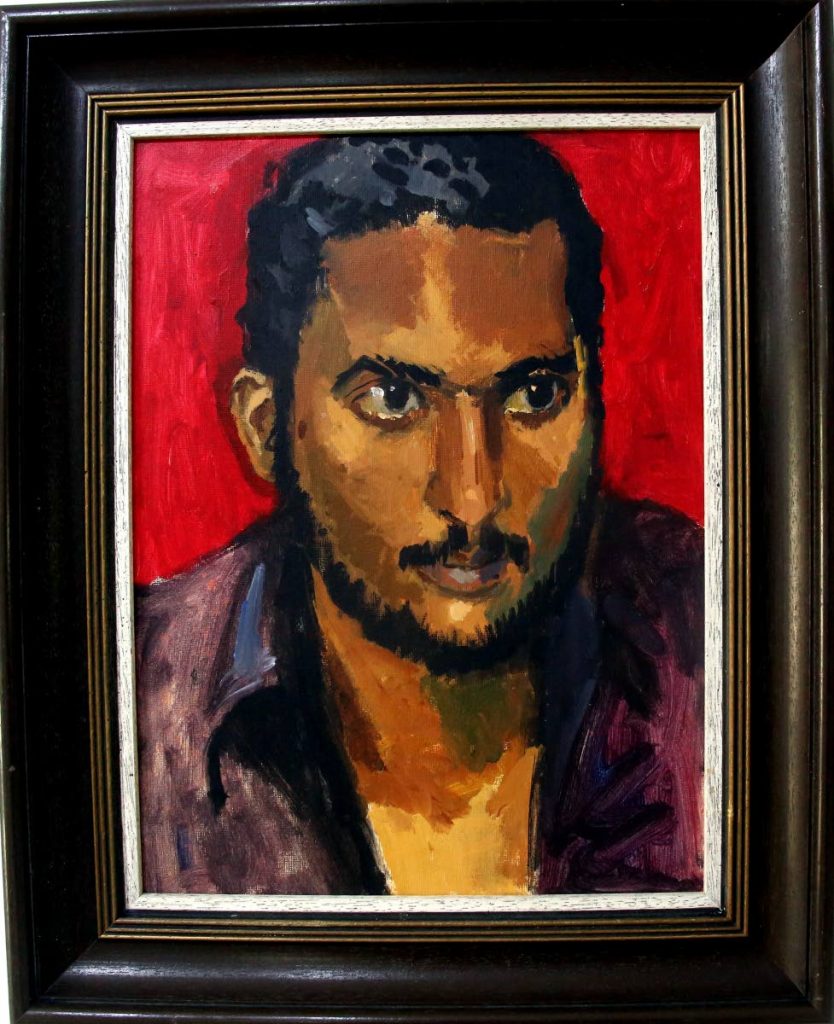

But tradition is represented in this show, and outstandingly so: for instance, there’s a glowing, jewel-rich picture by Boscoe Holder of a young, intense Wayne Berkeley, painted when both artists were less sleek than they later became. Like many of the portraits Holder made out of interest rather than because he was commissioned, this is a more considered work that holds the attention.

Alongside it are hung two women’s heads by Holder’s brother Geoffrey, one indeterminate and idealised to the point of anonymity, the other more individual but still veering into quaintness. The juxtaposition with Boscoe’s work doesn’t flatter them.

The show opens with three images by Leo Basso, a favourite of Ashraph’s. The first is a striking unnamed man, with an ambivalent, wary expression. And then come two well-known figures, little more than impressionistic sketches, but both informative. One is the bizarrely forgotten and yet unmistakable Albert Gomes, less corpulent than he was to become, but already jowly, stolid, droopy-eyed, sallow. The other is Atilla the Hun: youthful, moustached, ambitious, unpolished; not the city councillor and Legislative Council member he would become under his real name, Raymond Quevedo. Gomes too looks as if this may be the journalist, activist and supporter of the arts of his younger days, and not Gomes the politician. But, sadly, none of these three paintings is dated. However, Basso himself was younger than Atilla, so these may be very early works indeed.

Of the rest of the exhibition, those that most easily also fit into the category of conventional portraits are by the Canada-based Kareem Anthony Ferreira: a trio of three female figures. It’s obvious that these are people the artist knows and loves: the stylish Aunty B, the lively, friendly Deb, and Young Raeniece, who seems to be struggling to stay still, holding herself slightly stiffly and wondering what this is all about.

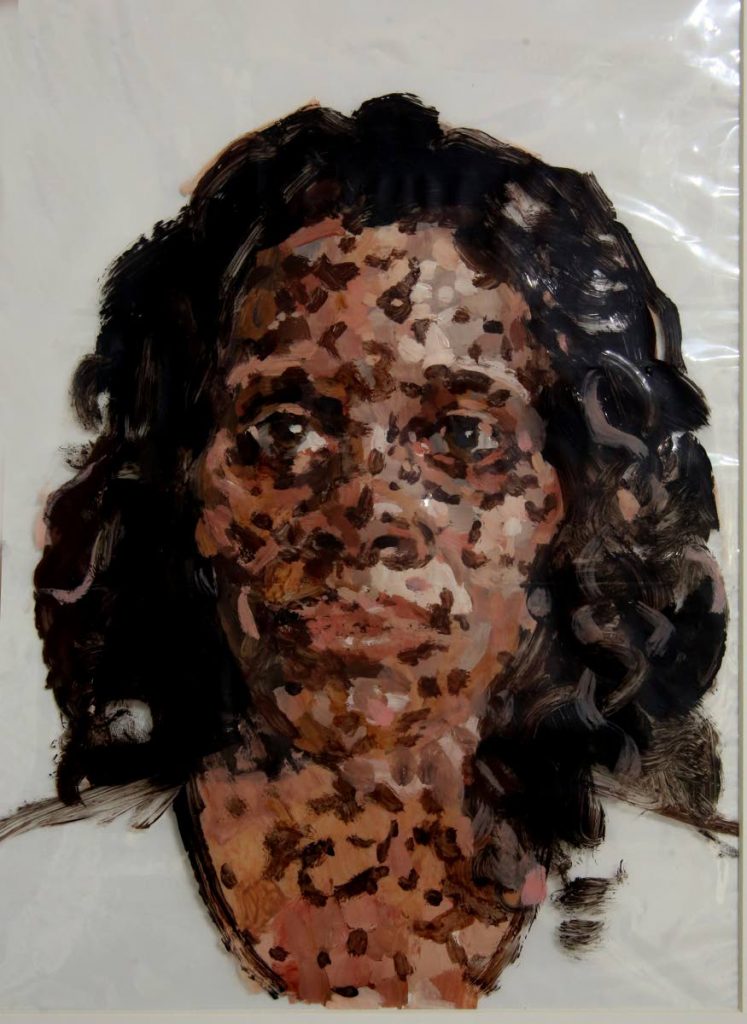

Equally intimate and unguarded are the four pieces by Jamaican artist Camille Chedda, a series called Shelf Life. They’re painted in acrylic on transparent plastic on a white background, using a pointilliste technique that lets the white show through; it gives them a fragmented air, as though the paintings are made of dried leaves blown together momentarily into the shapes of human heads that may disintegrate again at any moment. And yet they vividly convey the characters of the four women who gaze frankly out at the painter and the viewer. The appearance of an ephemeral form, combined with the impression of a durable character, leaves the viewer unsettled.

Paul Kain shows a series of images of real, “ordinary” people who have something remarkable about them. At first glance it may be only the colourful clips in their hair, extravagantly long red nails, or jaunty titles (Rudeness, Zesser) and accessories. But these are people who otherwise go unnoticed, and despite the flatness of his presentation of them, they leave the viewer stirred and saddened.

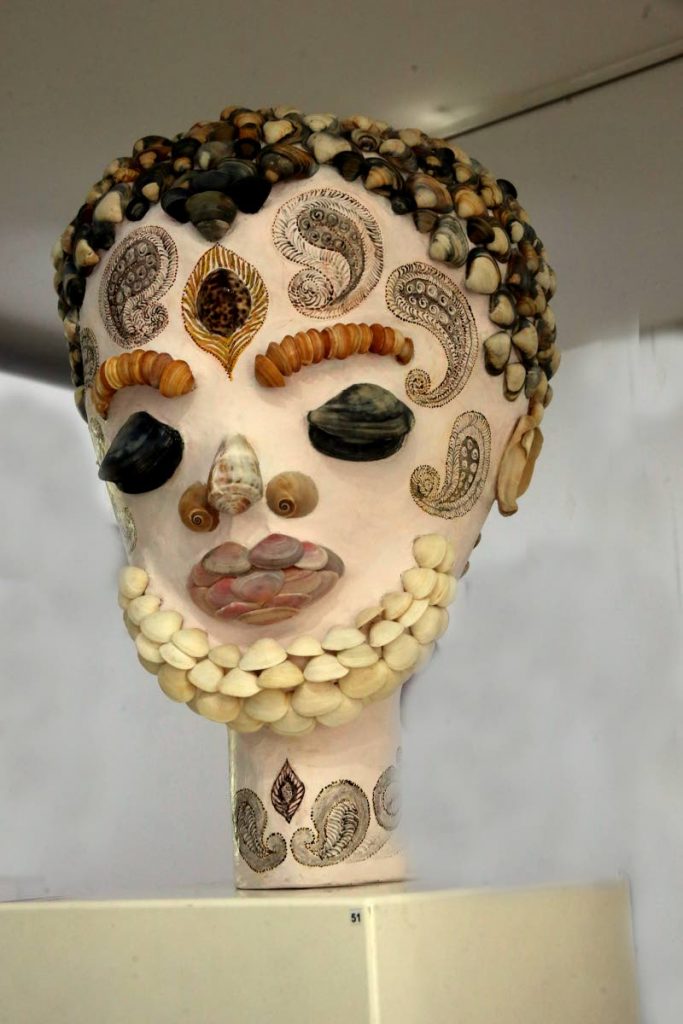

On a stand in the centre of the room is Wendy Nanan’s The Sadhu, a large, non-naturalistically shaped white head whose features and even hair are made of seashells: pale pink lips, grey eyes, whorled nostrils, and what may be a third eye formed from a cowrie on his brow. The paisley pattern that adorns his neck and forehead give him an Indian air; he resembles a benign deity, one who presides perhaps over the Temple in the Sea. Conveying personality, in modern times, is often one of the purposes of a portrait, but this sculpture is in an epic mode, as though it embodies a universal quality rather than more ephemeral or human traits.

He's flanked on one side by Luise Kimme’s bust of a young man, carved of wood, wearing a crown; though he may be intended as a portrait of the real Tobagonian Prince, he has been smoothed into perfection; he has the air of archaic Greek sculpture, an idealised ephebe.

On the Sadhu’s other side are two works by Shane Hanson Mohammed that stretch the term “portraits” furthest of them all. They are made of pairs of solid cubic concrete blocks, one stacked on the other. One is called Portrait of Central 2018-2019: the lower block is simply painted bright pink, and the one above has, sunk into one side, level with the surface, an unpainted metal bowl. The other, depicting a child’s room, has glass panels, a mirror and a Lego man set into the sides and an opening at the top; it contains small plastic toys in blue and yellow, a tennis ball, a plastic Slinky. It’s like being able to see inside a child’s head; perhaps it’s in that sense it could be said to be a portrait.

Likewise, Dean Arlen ostensibly evokes moods in his series Six Emotions of a Man, so that they come across as more of an inner than an outer portrait. The most basic indications of a face are scrawled onto the outlines of deathly-white heads: gap-toothed mouths in a rictus, eyes too close together, a yellow nose, features outlined in green and blue.

The Space inna Space gallery is tiny, though the plain floorboards and white walls make it seem capacious. So there is much more, such as Haitian artist Tessa Mars’s juxtaposition of realistic drawings of a nude, sombre woman with contrasting abstract splashes of cheery colour, including perky male genitals; Embah’s naïve but satisfying Pan Man and an untitled full-length figure of a woman; Jaime Lee Loy’s fabric-shrouded pictures of women, which hint at entire novels.

And in addition to the work itself, the show also offers food for thought about portraiture in local art: what it means, whether there is enough of it and if not, why not.

Portraits runs at the Space inna Space gallery, corner Carlos and Robert Streets, Woodbrook, until December 5.

Comments

"Space exhibition explores what portraits mean in local art"