The more things change...Crick Crack, Monkey, 50 years after

EINTOU SPRINGER

“But the darker you are, the harder you have to try, I am tired of telling you that what you don’t have in looks you have to make up for otherwise.”

It is 1970. The drumbeats of Black Power, that had been long muted, are now at an inescapable crescendo...The Carnival in February had signalled the deluge to come.

We descended into the city from East Dry River. Our J’Ouvert band was Pinetoppers, The Truth: Before, Then and Now.

“Before” referred to the glory of Africa before the holocaust, “Then” was the period of enslavement, “Now” reflected the militancy of the time.

There is ferment in the artistic community. A dramatic break occurs in Derek Walcott’s Trinidad Theatre Workshop and Slade Hopkinson leads his young theatre radicals into the Caribbean Theatre Guild. It is also the year in which theatre activists form the National Drama Association.

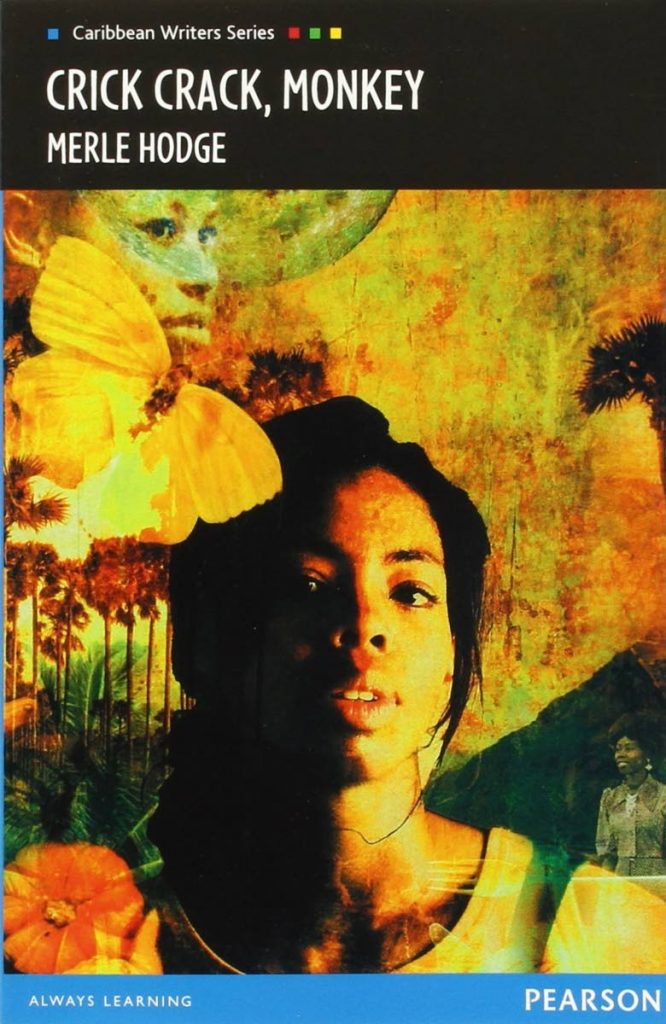

It is the year in which Merle Hodge publishes a deeply significant novel, Crick Crack, Monkey. A people’s literature presents us to ourselves in relentless scrutiny, in all our beauty, frailties, ugliness. It gives us the opportunity for self-love as well as self-criticism and the opportunity for transformation.

In this year, 2020 – in which the novel turns 50 – once again I thumb through its well-worn, well-loved pages. I am left to marvel not only at the many similarities between the then and the now, but also the accuracy with which the novel portrays the many matters of concern igniting the passion, the anger fuelling our marching feet.

Then as now, the issue of the damaging effect of a colonial and elitist education system looms large, as indeed, it does in the pages of the novel.

Within its pages is, for me, one of the most poignant moments in all of our literature. Duncy Joseph spells out loud, “G.R.A.P.E.S.,” and proudly declares, “CHENETTE.”

I have never been able to find it funny. Then, and now, we are marked absent from our education system.

Crick Crack documents the shadism, the colourism, still existing in our schools as well as in the wider society; the notion of blackness as being a curse, the concept that being educated means to move away from one’s heritage, one’s food...

“Aunt Beatrice announced her firm intention to haul me out of what she termed alternately my ordinariness and my n-----yness.”

The issue of language is also a key theme. The novel lays bare the vast cleavage between the lifestyle of the ordinary poor, African and Indian, and that of the pretentious African middle class.

Of course, the novel mentions the then ubiquitous grassroots grandmother with the amazing knowledge of bush medicine and the magical kitchen of toolum, sugarcake, sweetbread and pone; grandmothers, of the warm, snugly nights of full-moon stories.

But the crick-crack was also about the mythological characters: la diablesse, soucouyant and douen, who could scare the children into good behaviour, even for a little while.

There is the uninhibited flow of the nation language, sometimes liberally, raucously spiced with the mildest of perceived expletives. Tantie shakes her “melodious backside’’ (Lovelace) in the face of the world, as she has done for centuries. This is the language of the grassroots matriarch, Tantie, not a cause of temporary mirth, but a link to a history of strength, of jammetry, of taking on all comers, in defence of all the children she nurtures. And it does not matter if they come from her womb or not.

This is an example of our Caribbean nation languages, as Kamau Brathwaite termed them. In Negus, Brathwaite challenges us, “Where is your kingdom of the word?”

Another seminal novel that also looks at colonial education and the African child. George Lamming’s In the Castle of my Skin, speaks to the liberating power of our nation languages: “We had talked and talked a lot of nonsense, perhaps. But anyone would forgive us with the sea shimmering and the sand and the wind in the trees, we received so many strange feelings...We weren’t ashamed. Perhaps we would do better if we had good, big words, like the educated people, but we didn’t...language was a passport...You could say what you like if you know how to say it. It didn’t matter what you said. You had language, good, big words to make up for what you didn’t feel. And if you were really educated and could command the language then you didn’t have to feel.”

I must say that contrary to what many believe, Merle Hodge has never advocated the universal use of the nation language, but rather the importance of being bi-, indeed, multi-lingual.

Aunt Beatrice, the almost alter ego to Tantie, trapped in her middle-class aspirations and “passport language,” pours scorn on the speech, clothes, food, and lifestyle of her grassroots relatives. She scorns their associations with the Indian families who were their neighbours and friends.

In 1970, despite the betrayal of the Roman Catholic archbishop, bowing to the pressure of his middle-class church people, and the threats of violence from racist Indians, rural Indians welcomed us on that historic march, bringing us food and water, instinctively understanding, the deep political and ideological meaning of the moment.

The brutal instances of corporal punishment outlined in the novel are now, thankfully, no longer permitted in our schools. I was, however, reminded of the plaited tamarind whips mercilessly flailing my black back in San Juan Presbyterian School. I remember the long red welts and swollen hands. My mother, angry in her helplessness, tended to my injuries with soft candle melted in warm coconut oil spread on the leaves of the wonder of the world plant.

And at Carnival time, the novel documents the rejection of the “n-----yness”; that very thing that had birthed the festival. Aunt Beatrice’s proper, middle-class daughters are only permitted to play in special bands where they are protected from that n-----yness.

What a thing. Think about the clear colour and class segregation that now exists in our “all ah we is one” Carnival. And the Carnival magazines, in whose pages, unless you are “agency brown” or lighter, for sure nobody eh taking out your picture. The Carnival has in fact, gone westward; taken over and commercially exploited by the very social classes that once scorned it. Tonnerre! These days Laventille people caarn even sell a sno-cone Carnival time.

Fifty years since 1970. Fifty years since the publication of Crick Crack.

In 1982, Merle Hodge was very active in creating an education system relevant to the people of Grenada, as part of that other revolution that began in 1979 and was so cruelly aborted in October 1983.

The universe must be howling in acerbic mirth at the cries from the Americans who are now complaining of foreign interference in their government. All praise to George Chambers...

I still have copies of the Marryshaw Readers that she designed and scripted in her attempt, as part of the Maurice Bishop government, to create an education system that marked the Caribbean child present; an education system that would fit into what Kamau Brathwaite called our “geo-psychic space.” Maybe the mothers at the ministry would be interested in looking at them.

During that brief period, one could hear on Grenada’s radio station more of our own poetry, kaisos, our plays, than I have ever heard on any radio or TV station in Trinidad. I have sat in sessions with Merle Hodge, Lamming, Lovelace, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, Errol Jones...One could run into the poet Malik or Gene Lawrence...or...or...Oh what a wonderful time...such as dreams are made of...

Fifty years after the Black Power Revolution and the publication of this book, how much have we progressed?

The eye of the novelist cruelly, lays bare the deeply entrenched divisions in the society with humour, pathos, but ultimately, in all its bitter truth. Tantie, with the clarity of her grassroots vision announces, “They doh much like black people up there,”

“Up there” is the United States, then seen as a place to which the lucky ones could escape. She is not at all excited that her godson Mikey is going there. You can almost hear her raucous laughter, and the “I told you so” as a response to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Nobody rushing to go there now between the rampant racism and equally rampant pandemic.

Our novelists, our poets, our playwrights, our kaisonians cannot continue to be seen only as providing entertainment; though indeed, that is not to be disparaged. Those with the consciousness, who function at a level beyond the mind-numbing noise, can make an invaluable contribution to moving our nation forward.

In my own days at school, I was introduced to the best of English literature from fourth standard in primary school. By the school-leaving class, while I waited to go to secondary school, my beloved St George’s, I was introduced to and could recite by rote some of the greatest of the English poets.

Consequently, in my dreams, I was the beautiful blonde girl running through fields of daisies. At that time, there was not the awareness of, or indeed, the wealth of Caribbean literature that now exists. It was not until sixth form that the world of Selvon, Learie Constantine, CLR James, Alfie Mendes, Mittelholzer, JJ Thomas, prodded my consciousness, and I could see my reality reflected in my “kingdom of the word.”

There is no excuse, nowadays, for the syllabus not to be replete with our literature.

Still, as we root ourselves, in our own beingness, we do not surrender our right to experience the world’s finest literature. It is a time to embrace the possibilities of transformation.

Comments

"The more things change…Crick Crack, Monkey, 50 years after"