What being a paperboy taught me

BitDepth#1222

I WAS a paperboy.

Beginning in my early teens, having only recently moved to Woodbrook from St James, I had the opportunity to take over an existing paper route from a delivery professional, as I’d imagine we might call them today.

It wasn’t a big route. Around 90 or so papers, most of them concentrated near PoS 10 the eastern end of Woodbrook where I lived, with a few outliers on the far western end.

There were enough papers to comfortably drape over the front handle bars of my bicycle to deliver in a single run. Not on Sundays though. The hefty Sunday editions, with their supplements and sections, were unwieldy beasts.

The Sunday paper defied the tight roll and bend that turned a few dozen sheets of flimsy newsprint into a missile.

To deliver a Sunday paper, you had to tightly fold it into itself like a taut blanket of paper.

If you did it right, you had an aerodynamic wing that would soar impressively into a front porch, whizzing over the madly snapping pothound in the garden.

Fold it poorly, and it would explode into a millisecond’s worth of fractal art before floating off to every corner of the leafy green moat that lay between the front fence and the safety of the porch.

The blanket of newsprint would have barely settled in a breathy hush before the hellhound began tearing it all into unreadable shreds.

My first bosses were Robert Moore and Gary Cardinez, men who seemed to know who each of their customers were.

Their feel for the delivery systems they put in place was uncanny.

Comatose in bed after a dramatically ill-considered Saturday night, I could be assured of a call of measured annoyance from Cardinez who had probably already fielded two or more calls from subscribers.

I delivered a steadily diminishing pile of papers for the next six years.

There was something about delivering papers as a job that remains unique.

You meet very strange people.

There was the gay couple on Cipriani Boulevard. The heavyset partner would come to the door when I came to collect payment, mostly naked with his gut spilling over his briefs with an equally overweight bulldog uncertainly testing largely unused legs wobbling alongside him.

The woman in the apartment – at least I think it was a woman, because I never saw the person’s face properly – who would tersely hiss, “It’s in the postbox.”

Sometimes you need to do a job to understand that you never want to do it again.

By 2001, papers were being delivered by an anonymous arm from a car stacked high with papers, each in a plastic bag.

It seemed oddly industrialised and distant. That arm wasn’t terribly interested in anything more than clearing the wall. No wrap. No aiming. No craft.

For me, delivering newspapers was a gateway drug into the business of journalism. Years after I had begun writing, my mother kept teasing me that the ink from handling thousands of newspapers had permanently tainted my blood.

The annual visit to the office for the paperboy’s Christmas party introduced me to the throb of the Guardian’s massive letterpress printing engines, the Express’ party required you to cross ink-stained concrete in the driveway, tracking black footsteps behind you.

It’s not a job that exists in that form anymore. That intimate connection between paper and customer has been broken forever and digital links don’t really replace it.

Being a paperboy was, ultimately, the truest introduction to journalism, an enormous effort for a pitiful reward, garnished with a sense of shimmering but inexplicable accomplishment.

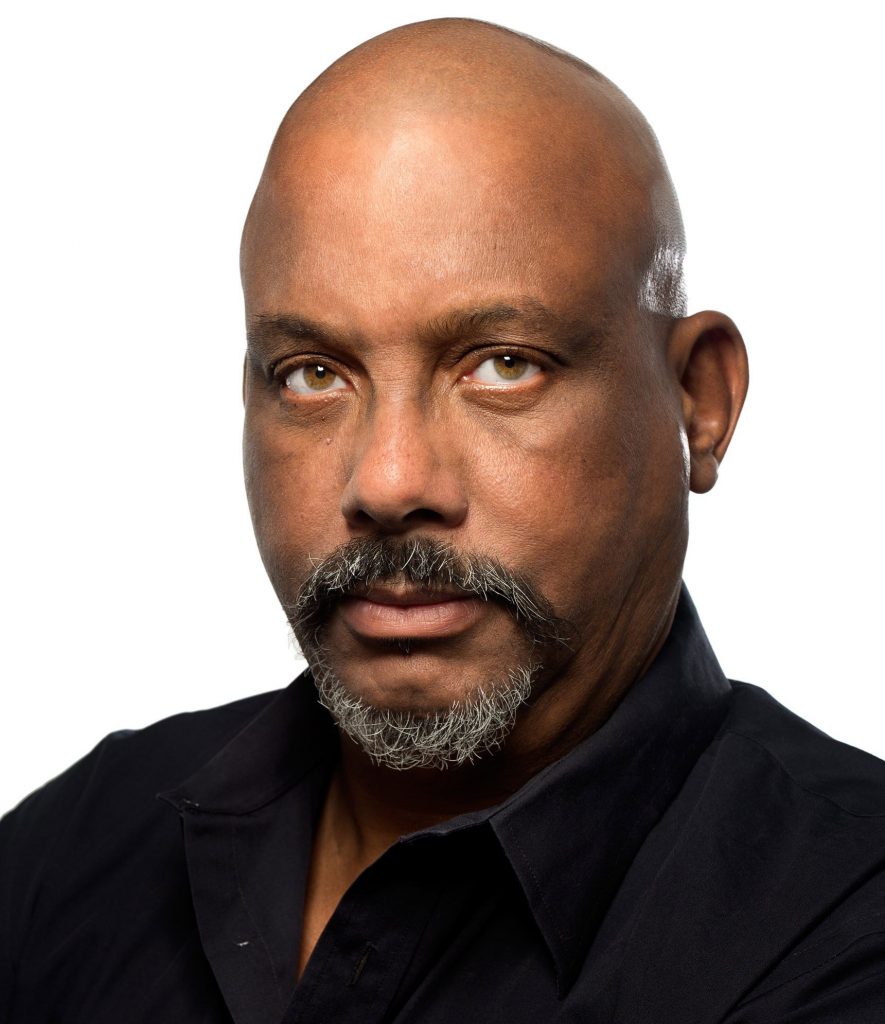

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"What being a paperboy taught me"