Artist Honeywell’s second solo show: Seen through a Scarlet Eye

Hassan Ali

The Scarlet Eye, Aurora Honeywell’s second solo show, offers a fairly intimate viewing. The already-snug space of the Frame Shop in Woodbrook has been cut to roughly half its regular size for the six-painting exhibition.

It’s quite a contrast from Honeywell’s first show, Orchid Museum, at the nearby LOFTT Gallery. Those who saw that show will know the walls were packed with paintings and some pieces were even hanging from the rafters.

First with Orchid Museum, and now with The Scarlet Eye, Honeywell challenges notions of the feminine spectacle. Her first vision was much more tender: its visual vocabulary was primarily dominated by figurations of (mostly female) human bodies, flowers, small animals – and, on the more sinister side, snakes and mantises.

This time the artist has chosen the scarlet ibis as the central metaphor in her exploration of femininity as spectacle.

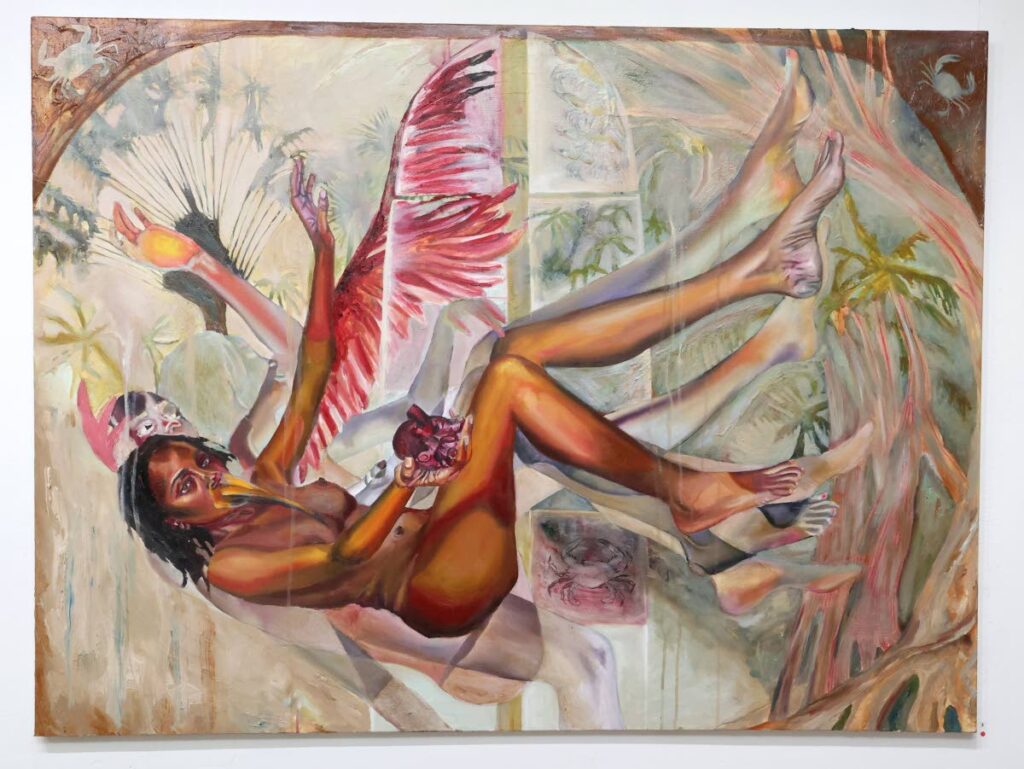

Every piece, save for The Inevitable, the first piece in the show, has an accompanying account with a matching title. These can be found on the table in the middle of the gallery space. The second painting, The Fall, features a nude female figure mid-fall, with multiple ghostly bodies and one main, solid one. There are two faces, one solid and a ghostlike one behind it. From the more defined of the two left arms of the figure, an ibis wing sprouts; at the end of her other left arm, a yellow mango sits in her palm. In her only right hand is a heart. The figure’s mouth is replaced by a beak.

The writing on this piece notably mentions that the Woman-Ibis “offered her humanity like a ripe fruit. In plain sight she carved out her heart and placed it squarely in her outstretched palm so the world could know her.” It mentions spectators below “bleating” (sheep) whose minds were “stinging” (bees – hive minds) with hypotheses about her; these spectators are not pictured in the painting.

It seems that this piece is fundamentally attempting to describe a monstrification. The “burdening” of the figure seems a fundamental denial of her implicit humanity. The transmogrification of the figure’s physical form on the canvas serves as a visual representation of this process of dehumanisation through narrative which so often happens to women in society. Within the contemporary visual art scene, many young women have shared their experiences of being derided and denigrated for exploring non-traditional themes in their work. At this point it’s also a Trinidad and Tobago truism that anything a woman does or is involved in, even against her volition, will somehow warrant a negative and scandalous interpretation from at least one person on social media.

By the fourth piece in the show, the Woman-Ibis is wearing a white dress and her wing is now also white. Who Am I Supposed To Love features St Chad’s, the abandoned church in Chaguaramas, in the background. The sky on the upper left side of the painting is purple-pink, with shadowy figures of trees growing into it. The sky as seen through the windows of the church is its regular light blue and the trees look a little more real. On the ground, a few lambs can be observed: one is frolicking, two are lying in the grass, the last – the most foregrounded one – stands at the edge of the canvas with its eyes trained on the viewer. On the right of this lamb, the Woman-Ibis figure and her ghostly echoes are once again present.

To address the colour change: in the narrative crafted for the show, a key phrase is: “You are what you eat.” If you’re unfamiliar, the ibis gets its red colour from the food (mostly small red crustaceans) it eats. At this point in the narrative, the Woman-Ibis has eaten of the sheep – lambs – that were observing her and has tasted their bilious remarks and perceptions of her.

Sociologists and psychologists refer to the Rosenthal or Pygmalion effect, in which

the expectations or narratives that we set for a person (that they’ll be a Straight-A student or gang member) can lead to them behaving in those ways. As a result, the bird has now taken on sheep colours.

Most interestingly, the mouths on all three instances of the figure here are distorted or covered in some sense: one has a beak, the other one has a red mask and the last has its mouth area disrupted by rough grass. Her voice, perhaps even her appetite, is lost.

Overall, the show attempts demonstrate, empathetically, the eternal plight of a woman attempting vulnerability (or at least one facet of it): to be constantly between that space of subjective and spectacular experiences; to be human and to be a monstrous thing for even asserting one’s own humanity.

If this is, in fact, the goal or even close to the intended goal of the show, then it’s safe to say it’s succeeded. Honeywell’s work is viscerally gripping and this, only her second, is significantly more concise and clearer in its aim than her previous exhibition. This feat is even more impressive when one considers that the shows occurred only half a year apart. Honeywell is certainly one to keep on your radar.

The only criticism of The Scarlet Eye is that perhaps the commentaries could have been placed on the walls next to the piece of art. In this way, the show could have leaned deeper into this multimedia flirtation between written narrative and visual (in this case, painted) spectacle.

The Frame Shop is on the corner of Carlos and Roberts Streets, Woodbrook. The show is on until December 7, and opening hours are 9 am

-

5 pm Monday-Friday and 9 am

-

3 pm on Saturdays.

Comments

"Artist Honeywell’s second solo show: Seen through a Scarlet Eye"