Professional perspectives on new cybercrime laws

BitDepth#1446

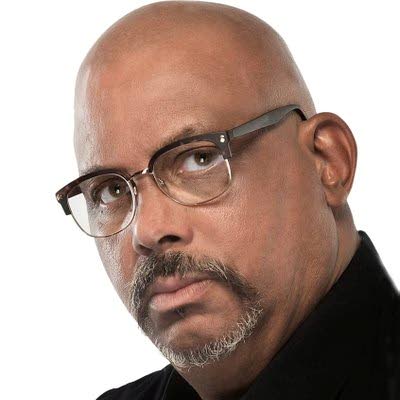

Mark Lyndersay

A SPIRITED discussion of last week's column on LinkedIn offered wider perspectives on the cybercrime laws which the Attorney General promises for later in 2024.

Kwesi Prescod, principal consultant for Prescod Associates, noted that an ethical hacker would not be affected by the cybercrime act because that person would be acting with authorisation.

Kevon Swift, a digital policy expert specialising in digital trust issues at LACNIC, went further, dismissing the concern as "nonsensical."

"Cybercrime law squarely addresses unlawful conduct, which is defined and sanctioned according to international standards. Authorisation, based on decision by a duly competent court, is prescribed under the amended version of the Interception of Communications Act, 2020."

Swift noted that there was an issue with clause six, which criminalised "A person who, intentionally and without lawful excuse or justification, remains logged into a computer in a computer system or part of a computer system or continues to use a computer system."

He noted, "[It] need not even be considered a law as automatic sign out is a prominent feature by design for secured computers. But unless we modernise the descriptions of unlawful behaviours in 2017 cybercrime bill, we will be sifting water with a colander."

On the question of crafting legislation that's flexible enough to evolve meaningfully in a changing environment, Prescod noted, "The Digital Transformation Plan still isn't published. The consultation hasn't put a green paper out yet. This is the first time in 20 years that TT doesn't have a published plan. That failure alone is an indictment of sorts.

"The over-regulation narrative is hogwash. Enactment of existing laws such as data protection only requires the hiring of staff – without which the digital ID thrust could be subject to judicial attention – or electronic transactions, which only needs the establishment of certain administrative frameworks to recognise operations for legal grounding. In the latter instance, the courts themselves have adopted the model proposed and forged ahead to become the most digitally transformed agency in the public sector."

One commenter suggested that a consolidation of cybersecurity roles in the public service would follow its planned restructuring, strengthening the national security profile by centralising the function within government.

Prescod did not agree.

"The restructuring of the public service has been ongoing for 30 years, since Gordon Draper," he argued.

"The re-evaluation of public sector positions still isn't done. The service commission is still hiring 'typist/stenographers' when no one actually does stenography."

"We are behind again, and talking while we become more uncompetitive," argues Prescod.

"We pioneered the need for these frameworks in the Caribbean in 2008 then stalled. Jamaica and Barbados have functioning data commissioners. The OECS countries have digital IDs deployed for multiple government services and updated their telecoms laws to regulate the digital economy. Grenada has laws recognising NFTs.

"In TT, we're talking in circles, achieving nothing, without even a published plan. We're seeking to undermine existing private sector endeavours – inconsistent with long-standing macroeconomic policy – instead of focusing on a role (laws and market structure) in areas where the private sector has failed to act."

"One point we keep missing in national conversations is that the overwhelming majority of cybercrimes are transnational and would therefore require international co-operation, rooted in harmonised law, to facilitate investigations, evidence collection and eventually prosecutions," said Kevon Swift.

"The proposed articles are not unique, nor are they expected to operate only locally or in a vacuum. If unlawful behaviours are not adequately criminalised locally, there is no basis on which law enforcement can work with foreign counterparts, or internet intermediaries (e-mail, social media, cloud services providers), so no justice can be delivered.

"Evidence transfer, for volatile evidence such as digital evidence, requires dual criminality to be established (harmonised/equivalent substantive provisions) with a minimum penalty of one year's imprisonment in order for expedited assistance to occur outside traditional mutual legal assistance treaties, which can take 11 months or more to deliver results.

"But there are a lot of informal co-operation activities, particularly involving threat monitoring and analysis, which can occur outside these laws. Local ethical hackers would need to bolster their affiliations with trust communities, such as (regional) CSIRT associations and even global ones such as FIRST.

"At LACNIC events, we host the LAC version of the FIRST conference and we've been fortunate enough to have actors such as TTCSIRT participate there. For things like penetration testing, a client's authorisation is still key. Anything outside of that, especially probing secured computer systems, is globally accepted as an offence."

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"Professional perspectives on new cybercrime laws"