FLIP in Paraty

After the gold, the slaves, the sugar and the coffee ceased being traded through the port of Paraty in southeast Brazil, and the population fell by 95 per cent to just 800 in 1950, nobody would have believed that an intangible commodity would replace them and breathe new life back into the marooned 17th-century town.

Culture, or rather the elements of what we deem as cultural pursuits, were always highly valued, from the beginning of time – music, drama, art, poetry, dance, performance.

In Paraty, literature has been at the heart of the town’s modern revival and helped bring that other modern economic driver – tourism – to this rare corner of the South American continent.

Everything used to arrive by sea in Paraty until in the1960s-70s, when a major roadway – Route 101– was built, linking Brazil’s north to its south. This 4,000-km road connected Paraty and beyond to the rest of the country for the first time. The place was a latter-day discovery for Brazilians and foreigners alik,e who now flock to the charming colonial town, which has been named a Unesco World Heritage Site.

Paraty never really produced anything the world wanted in sufficiently large quantities to matter, but historically, it has been a funnel through which important items pass, so thousands of copies of books turning up in makeshift bookshops is not so strange. And people flow in too, in droves, every year for the international literary festival, FLIP, which started in 2003.

It was the brainchild of Liz Calder, the fabled publisher of Salman’s Rushdie Midnight’s Children, which turned the little-known writer into a star when it won the highly prestigious Booker Prize in 1981. Calder also spotted Harry Potter and turned its author into the first literary billionaire.

With that same sure eye she spotted that subtropical Paraty was a jewel and that writers would gravitate to it for a long weekend of literary exchange and bonhomie.

She was right. They come for the literature, but also for the curiosity that is Paraty.

Arriving by the road that zigzags for at least an hour through the mist-thronged, densely-forested mountain range – a big brother to our Northern Range – you are plunged into the very familiar-looking (to a Trini) town with its quiet bay of golden sands, shrouded from the gentle sun by an army of coconut palms. Standing back from the wide seafront are the town’s low-rise, exquisite 250-year-old colonial buildings, all beautifully restored and maintained. Their uniformly whitewashed walls line the streets and their windows and stuccoed doorframes sport bright, primary colours. The overhanging iron balconies add a romantic air to the vista.

The streets of the old part of Paraty, a bit smaller than downtown Port of Spain and similarly arranged in a grid pattern, are famously cobbled, but not with conventional cobblestones. The unexpecting tourist is faced with riverbed stones or boulders of uneven size, shape, and level of challenge.

Those pedestrianised streets (to me, riverbeds) are definitely not meant for human feet. The slippery stones incline towards the middle and, with no sidewalk, you can only pick your way along, dodging the outdoor diners on their wobbly chairs.

This town centre was clearly and incongruously meant for four-legged animals, but only the rare clickety-clack of an empty donkey cart or smart, touristy horse-drawn carriage, squeezing its way through, further impedes very slow progress.

More curious still in Paraty is the novel colonial intention that the sea would clean the cobbled streets. Low-lying openings in the seawall allow salt water to enter during full moon and flood the streets, supposedly removing the detritus of human commerce. The streets were clean, but the area near the sea wall was distinctly smelly. Rain, lots of it, regularly floods the streets, and one must resort to elevated narrow footbridges in certain areas, but nobody is deterred.

Two multi-prizewinning Trinidadian writers appeared in last weekend’s FLIP programme – a first. Canada-based Dionne Brand and London-based Monique Roffey are our two most experienced writers, their many books translated into several languages. They were there to promote the Brazilian editions of their work.

After their panel discussions, which were warmly appreciated by large audiences, long lines formed for signed copies of Roffey’s The Mermaid of Black Conch and Brand’s No Language is Neutral and Bread out of Stone.

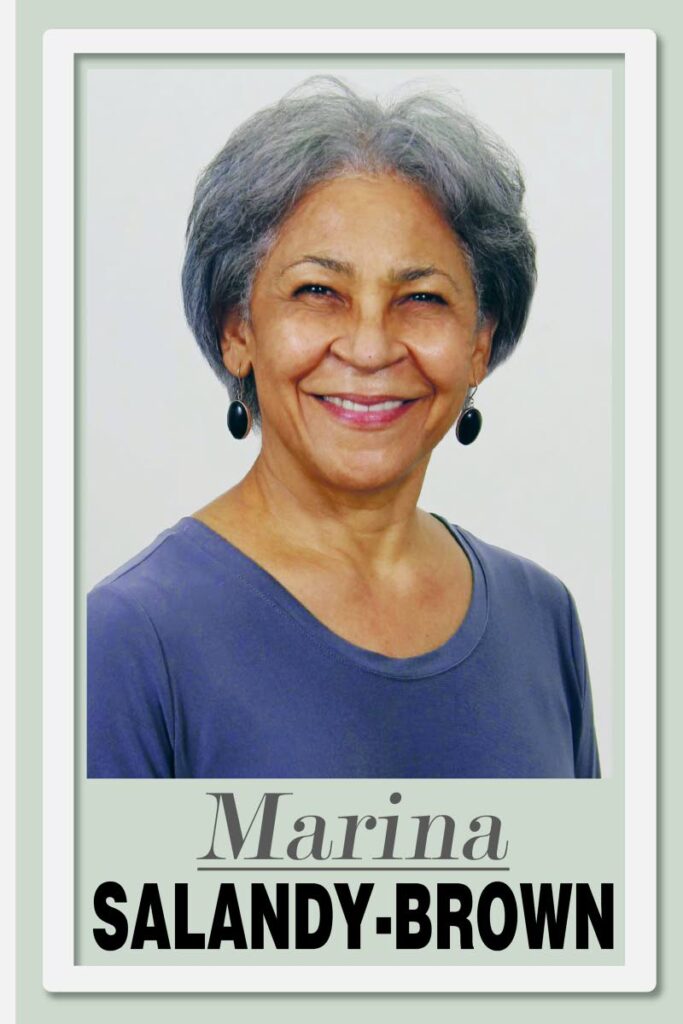

TT’s own literary festival, the NGC Bocas Lit Fest, is part of the network of literary festivals that drive book sales in dozens of countries, and many foreign publishers are big investors in our new and prize-winning writers, taking our stories around all the continents of our world.

Imagine, if the tide ever remained out on our traditional sources of wealth, it could well be that our culture – our pan, our mas, our art and our creative literary imagination – brings us back to shore. Paraty has less, but was reborn.

Comments

"FLIP in Paraty"