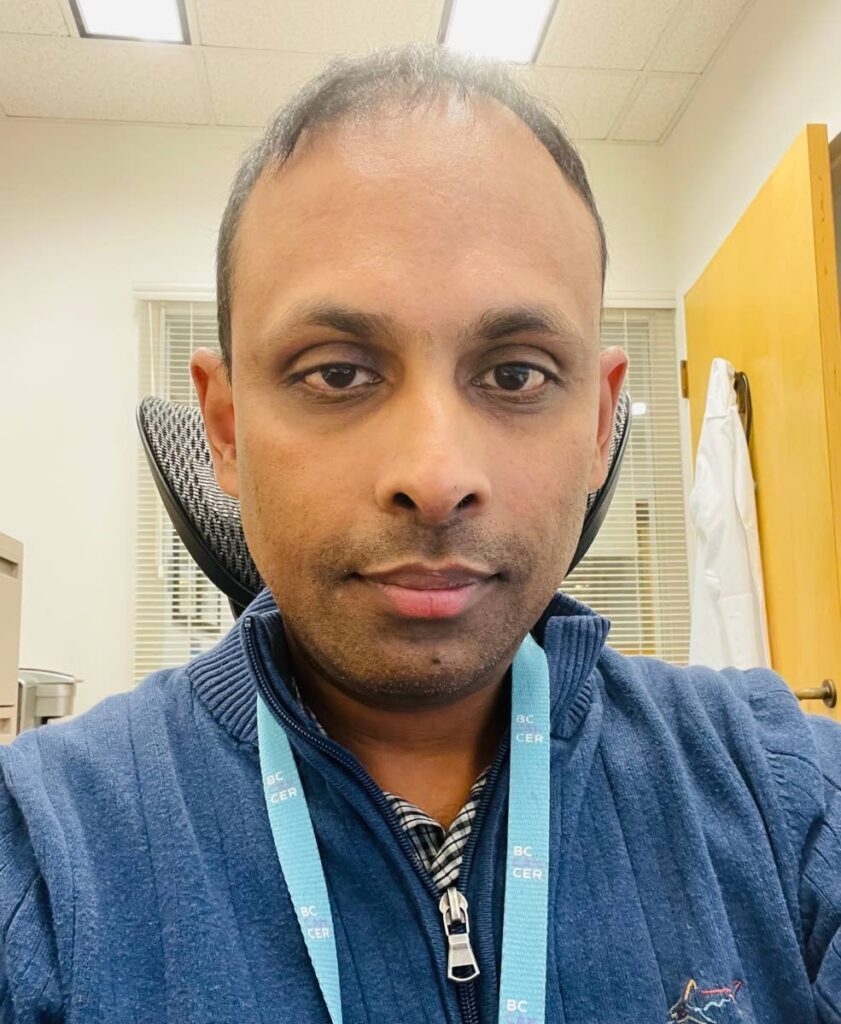

Advancing cancer research: A conversation with Dr Dylan Narinesingh

BAVINA SOOKDEO

In the world of medical science, few areas of research are as vital and far-reaching as the study of cancer. Dr Dylan Narinesingh, a seasoned doctor with 23 years of experience, and a radiation oncologist for 13 years, is at the forefront of cancer research.

He is radiation oncologist, BC Cancer, and clinical instructor, Department of Surgery, University of British Columbia, at BC Cancer – Fraser Valley Cancer Centre.

Narinesingh has been involved in many different areas of cancer research, primarily in breast and prostate cancer, since his initial training as an oncologist.

Earlier in his career, while he lived in Trinidad and Tobago, his work centred on access to cancer care and utilisation of resources.

Asked what motivated him to pursue research in these fields of cancer and whether any personal or professional experiences led him to this area of study, Narinesingh said, “I have always had an interest, since specialising in radiation oncology in breast cancer.

“My passion for breast cancer research came from an inspiration driven by my patients and my mentors.

“Oncology is a field where you feel the joys, the anxieties and the pains of your patients through a journey. Research is the way you can help to impact your patients, their families and society, present and future.

“When I trained, I worked with breast radiation oncologists who had the zeal and passion to challenge the thought process.”

When he met his wife, a radiologist, he said, she was researching mammography and what were the barriers to women ‘s going for screening.

“ This study, her constant questions and its results piqued my interest in the public health aspect of breast and prostate oncology in TT. I was involved in administration at many levels and saw oncology from a different lens.”

Narinesingh reiterated that at BC Cancer, he has been involved in studies and trials on de-escalating radiation for patients with breast cancer.

“All breast cancers are not the same,” he said, “and as more and more tumour-profiling tests become mainstream, the question to be answered is, ‘Can these tests help to predict which patients are at lower risk of recurrence, so that they may require less extensive radiation treatment fields or can avoid radiation totally?’”

These areas of research involve large teams at different centres, he said, and could change how breast cancer is managed for women worldwide.

“I also have an interest in seeing if the total number of radiation treatments can be reduced for some women.”

What methodologies and technologies does he employ in his research?

“In the clinical trials I am participating in trials where we are using tumour-profiling, Oncotype DX, which is used routinely in many hormone-positive breast cancer patients to determine if there is the need for chemotherapy or not.

“However, the application of this data to patients in the radiation setting is still to be answered, and patients have the opportunity to participate at my centre in a study to see if this result can lead to a de-escalation of therapy, that is, not having to treat the lymph nodes.”

Asked to share key findings or breakthroughs from his research that he believes have the potential to make a significant impact on cancer treatment or prevention, Narinesingh explained, “In some of the earlier work with my wife, we looked at women’s knowledge, practices, attitudes and beliefs to screening mammography for women in South Trinidad.

“We found that there were cultural sensitivities that needed to be addressed to improve the uptake of mammography. Most women would have had their mammogram requested by their physician.

“I have since then and continue to remind women to be their advocate for screening mammography – ask your doctor. I always tell my patients, ‘Chat with them and if need be, get your mom, sister, neighbour a mammogram for Christmas or their birthday or Mother’s Day – it’s a gift that can change a life.’”

One piece of theoretical research that has had an impact on breast cancer treatment, he said, “Controversial as it is, is work done with my colleagues in BC Cancer Vancouver. This looked at the physics behind the clinical data that bolus (tissue-equivalent material) put on the chest wall for patient with mastectomies with no adverse features only provided increased side effects, but no clinical gain...

“With the trials to close and results some years away – clinical trials that I am working on – if there is a positive result, can mean that some women, where the breast cancer has spread to the lymph nodes and have a tumour-profiling test called the Oncotype DX with a low score, can avoid radiation to the lymph nodes.

“Another study with results some years away can change the standard of care for patients with breast cancer spread to the lymph nodes, in that they will only need five treatments of radiation.”

How does he think the medical community and policymakers can better support cancer research initiatives and translate research findings into practical applications for patient care?

“Supporting cancer research is important. There are many areas of research, and many times the research that will most greatly affect a local community is not the high-level research, but research that is supported, encouraged and funded to improve provision and access to care, as well as identifying subgroups at risk.

“I think these are important, as public health policy needs to be data-driven. Policy-makers need to encourage these areas of research to make informed decisions and plans.”

He had advice for people looking to reduce their risk of cancer or those currently undergoing cancer treatment.

“I feel very strongly about screening. I encourage women to get their screening mammogram and be an advocate for themselves and others.

“In Trinidad, there are many ways to get a screening mammogram (public hospital, Cancer Society and private hospitals).

“When to start screening for breast cancer can vary across countries, but most would agree, as we do here in Canada, that for the average woman, screening for breast cancer should start at 50 and continue to 74 years, with a mammogram done every two years.

“Screening before 50 and after 74 can be discussed with your doctor.

“The aim of screening is to pick up breast cancer before it presents with symptoms, for example, a lump or pain.

“Finding an abnormality on screening mammogram does not always mean that there is breast cancer, and sometimes more tests are needed.”

He pointed out that routine breast self-exams as a part of breast cancer screening are not usually recommended by many groups, because they have not been shown to be effective in detecting cancer or improving survival rates.

But he added, “I still recommend that women be aware of their own breasts, so that they can let their doctor know if they feel something abnormal.”

Saying Pap smears are also important for screening for cervical cancer, he encourages women to speak to their doctor or nurse about getting them, as they can save lives by picking up cervical cancer early.

“I had done a study looking at the cost of treating cervical cancer in the SWRHA (South West Regional Health Authority) between June 2009 and June 2012,” he said.

“The cost was in excess of $10,000,000 over the three years, just for the SWRHA.

“I also recommend the HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccine.

“The Ministry of Health has a good handout available online that addresses this topic really well. It is aptly titled, HPV Vaccine is Cancer Prevention. I encourage parents of 11-12-year-olds to take advantage of the vaccine. Many cases of cervical cancer can be prevented by screening and the HPV vaccine.”

He stressed that palliative care is dear to him, saying that over the past decade it has become “more and more accepted and easier to access thanks to the hard work of many, including the Palliative Care Society, Drs Jacqueline Sabga, Richard Clerk, Stacey Chamely and Chelsea Garcia.

“Palliative care does not equivocally mean hospice care, which many health care professionals and the general population believe. I recommend to my colleagues and encourage my patients and their families to be advocates, so that referral is made early with a diagnosis of an advanced (not curable) breast cancer. Some patients with a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer (cancer that has spread to other organs) may live for years, with advances particularly with newer drugs (systemic therapy).

“Early referral to palliative care makes the journey an easier one.”

Comments

"Advancing cancer research: A conversation with Dr Dylan Narinesingh"