Journalism needs commitment more than it needs AI

BitDepth#1416

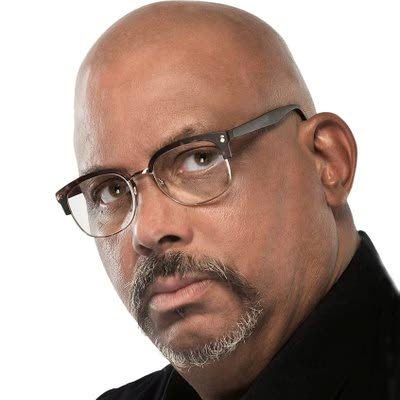

Mark Lyndersay

LAST MONTH, Media InSite hosted a seminar on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in communications. Working to appear useful on a panel discussing the rapid incursion of AI-generated text and images into communication, I spent quite a bit of time thinking about how journalists might navigate this nexus of rapid evolution.

The transmission of news was once a small information fireplace around which the nation sat, and there was a remarkable confluence of perspective in these sources.

The paper arrived in the morning, the radio offered newsbreaks during the day and the television news show Panorama on TTT offered a summary of the day's high-profile events, sometimes with moving pictures.

Today's media operates some distance from that era of homogenous news.

Fuelled by technology, the Web 3 ubiquity of publication and posting, the source of news has fractured into a quarrelsome flood of comment and talk back that isn't helped by the ease with which fact and falsehood blend into this flood of information.

Consensus on what happened yesterday has largely collapsed.

In this turbulence of fact and alternative fact, the job of journalism remains the same, cleaving truth from falsehood while presenting the best possible, most thoroughly fact-checked account of reality.

The rise in popularity of OpenAI's ChatGPT was only the first salvo in this modern assault on authorship. Adobe recently introduced a new version of its Photoshop image-editing software that includes in generative AI, making it possible for users to not just alter reality, but, with some deft text prompting, create it out whole of the digital aether.

It's notable that the company introduced this innovation on the heels of its Content Authority Initiative (CAI), a project that hopes to embed information into digital files that indicates the alterations done to them.

CAI is an effort at creating an open specification for incorporating alterations into file metadata information, but universal adoption is more elusive today than it was decades ago when EXIF and IPTC image metadata became part of digital file transfer.

With robots creating plausible sounding text and anyone able to spin fake photos out of digital straw, readers' trust in the authorship of the text that they read and the photos that they view is in danger of further erosion.

For that reason, the word that I believe will have the most impact on the practice of journalism in the coming years will not be AI, but provenance.

It will become increasingly important for media houses generally and journalists specifically to embrace greater transparency in the production of news.

The mechanics of reporting are not a secret sauce since the tools of production became available to anyone with the inclination to publish or broadcast.

The trustworthy journalism of the future will not gain authority by a presumption of professional superiority, but through a greater commitment to transparency in operations, process and production with the audience that media practitioners hope to engage and retain.

It's the difference between a declaration from a podium and a casual, explanatory conversation.

That's a tall order for a practice that has traditionally claimed equanimity, even in the face of increasingly pointed questioning of perceived agendas and biases.

Increasingly, journalists will be called to account by our own benchmarks, the six Ws that have guided its practice for decades, who, what, when, where, why and how.

The reluctance of the business to face the possibility of cross-examination is exemplified in its diffidence to the commentary section online. Online comments sections are a source of extensive trolling, distracting flame wars and unwarranted obscenity.

An editor can just trash a nuisance letter to the editor or cut off a ranting caller, but dealing with a flood of problematic comments requires time and effort.

Where comments sections are actually moderated, far too often the responses are arch and condescending instead of thoughtful and engaging.

The role of a public editor, an in-house ombudsman for the audience, was never engaged in TT, but every journalist must be ready to act in the role to ground the profession.

Moving from product journalism to process journalism is not an intuitive undertaking; when widespread falsehoods can be effortlessly manufactured via text, video and audio, the only defence journalism can offer is transparency in authorship and creation.

Executing these principles isn't particularly difficult, but they do demand a rethinking of editorial process, presentation and audience engagement that will invariably increase the cost of producing news.

Re-establishing authority and continuing to earn it in an environment dominated by machine-generated content will demand nothing less.

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"Journalism needs commitment more than it needs AI"