An uncommon entrance

BitDepth#1413

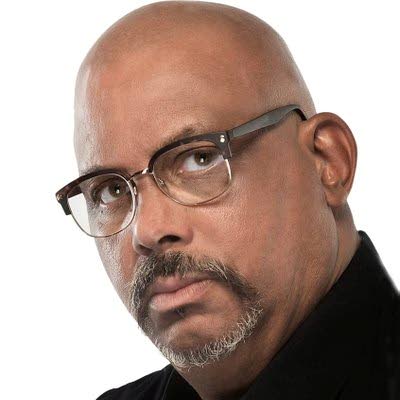

Mark Lyndersay

TODAY, TENS of thousands of children will be given the results of a summary judgment on their capacity to learn.

It's the end of nothing less than a year of torment that, in its scale of intensity, associated stress and potentially turbulent outcomes, has already changed the lives of children who have only just begun to figure out their place in the world.

I know this because, like most citizens of TT, I walked this bed of fire myself.

Back then it was known as the Common Entrance exam, and the brinkmanship of the test was even more severe. There weren't as many government-run secondary schools. The nation was still to commit to the idea that all children deserved a chance at a secondary education.

To fail the Common Entrance was to fail at life before you began to live. The options for a pre-teen of limited means were severely limited.

I am the eldest boy of three children and my grandfather, in his almost bottomless wisdom, told my mother, "Make sure the eldest goes the right way and the others will follow."

So she yanked me out of a government primary school where I was demonstrably underperforming, and put me in an intensive private school under the tutelage of Oswald Romilly, a former secondary school principal (and recipient of the 1972 Public Service Medal of Merit – Gold).

Mr Romilly (to this day, thinking of him, I cannot imagine referring to him any other way) was a solid tree-trunk of a man, an utterly intimidating presence in the school he'd carved out of his Woodbrook home.

You did not attend Mr Romilly's classes, you sat up straight and you worked.

Two things happened because of this tutelage. I did well in my exams, getting a book grant and the school of my choice and I suffered with crippling migraine headaches almost up to the day of the exam itself.

Arthur McCrae, a family friend and general helper around my home, sat under a tree opposite Queen's Royal College with water and headache tablets while I sat the exam.

This year I returned to the exam, or to be more exact, this year the exam arrived. It was a turbulent end to two years of learning how to do school at home (quite different from concepts of home schooling) and a year of in-person grappling with the syllabus.

It was not pretty. There were tears. I could not, even with the answers before me, figure out the math for at least 20 per cent of the questions on most mock exam papers. I know for a fact that some of that math wasn't put before me until I was in my second year of secondary school.

The question should be asked. What is all this angst, stress and suffering meant to achieve?

It's not as if there aren't other alternative methods of assessing student capabilities beyond a first-past-the-post exam.

Soon after arriving at secondary school, it became clear that I was in a brilliant class. When the time for book grant distribution came around, students were called class by class.

More than half my classmates would stand to leave (their metal chairs screaming on the floor as they rose). But there were also students who had been placed there who would remain out of their depth for five years.

There was no catchment for them.

There is a fundamental unfairness in trying to bend an inflexible system to accommodate a child that doesn't fit.

I spent seven spotty years in secondary school before declining to pursue tertiary education.

Instead, I chose, without planning for it, a lifetime of continuous education, inspired by something my General Paper teacher, Archie Edwards, told me.

"We don't go to school to learn; we go to school to learn how to learn."

To this day, I can't remember anything about the actual Common Entrance paper I wrote in 1969.

I remember a day lit by brilliant sunshine under a cloudless blue sky, the red brick of QRC glowing vividly under the hard morning light.

I remember an old man (really just middle-aged) who sat patiently under a tree.

I wish every child who gets their results today the same kind of quiet, unflinching support as they find their way in life, and the opportunity to find an inspired path to eventual success.

That won't happen because of the SEA, and it will more likely be in defiance of it.

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"An uncommon entrance"