‘Better get used to it’ syndrome

A female visitor from Europe recently sent the following message to me after reading my article of June 11 – Millipedes on the Road – about the fast, crazy driving and multiple, sometimes fatal, accidents that occur on Tobago’s roads:

“I just read your article. I was in a taxi today and passed a car accident. Soon after, the driver started speeding up, passing car after car in the middle of the road while other cars were passing us on the other side. I started complaining loudly: 'Could you please drive more carefully? This is dangerous.'

"The driver looked surprised. The man in the back said (unfriendly tone): ‘Lady, I don't know where you come from but that's how we drive in TT. Better get used to it.”

In that scenario, the woman was, understandably, feeling vulnerable and endangered and was speaking out in an effort to be heard and to have her (and everyone else’s) safety needs met. Not only was that general, basic need not acknowledged, it was rudely and aggressively dismissed by a "better-get-used-to-it" verbal slap.

In a world where many men, from birth, are raised to feel that they are the "heads of the household" and, by extension, "heads of everything," it is easily imaginable that words running through the "surprised" driver’s head could have been: “Who she feel she is to tell me what to do and how to drive?”

Lurking somewhere in the recesses of his mind may have been the erroneous belief that women do not know how to drive – when, in reality, statistics gathered from multiple global studies confirm that females are superior drivers and have far fewer accidents than their male counterparts.

Having been addressed in what may have felt like a "commanding" manner by a woman (the "weaker sex"), the male driver could easily have chosen to further assert his manhood by speeding up "for spite" – to "show woman who is boss."

The male passenger’s "better-get-used-to-it" logic, apart from being a verbal strike delivered to potentially silence the female passenger, could have been his way of standing up for his "brotherman" in a competitive, testosterone-driven show of male bonding.

The unspoken narrative in his head could easily have been along the lines of: “Do we come into the kitchen and tell you women how to cook the food?”

Unmentioned in the visitor’s initial account of the situation was the other passenger in the back of the vehicle – another woman, who remained silent for the entire journey.

“She didn't say anything at first,” the visitor explained in her follow-up. “Only when we got out, she mumbled something, but I couldn't understand. Maybe it was not related to the situation.”

There are multiple reasons why the other woman may have said nothing. Perhaps she felt "It’s not my business." Perhaps she had slipped into instinctive self-protective mode, fearing what could happen to two women alone in a taxi with two easily overpowering, unified men. Maybe she agreed with the visitor’s reaction, but fear of speeding had rendered her voiceless. Perhaps she was comfortable with and accustomed to speedy driving, believing in the recesses of her mind that "men are better drivers" or that "men are here to keep women safe, so he knows what he is doing." Maybe she silently resented the "white woman" for coming to "our island" and commanding what to do and how to do it.

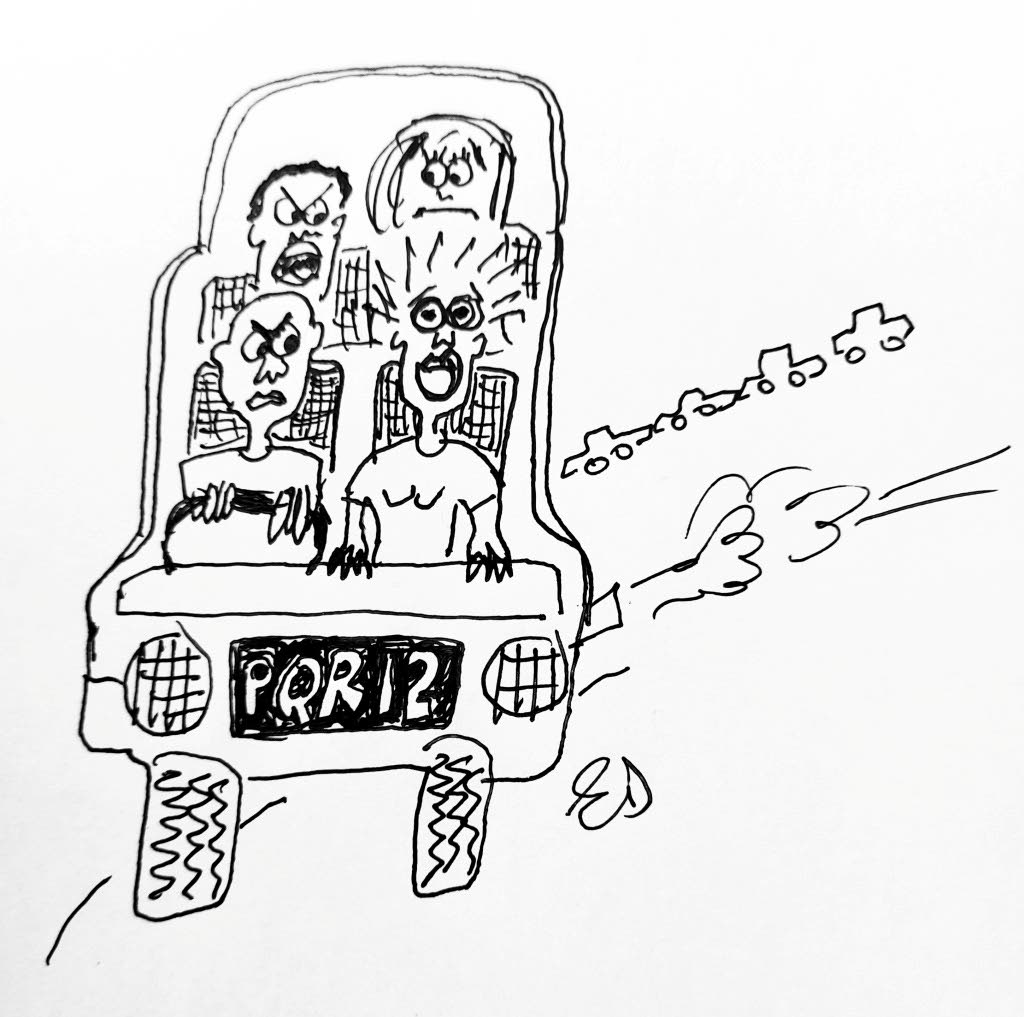

What appears on the surface to be a simple, everyday taxi scenario could, on a deeper level, be fodder for a play or film – The Taxi – in which the relationship dynamics of four characters, confined to a vehicle, drive them deeper into the potholes of individual and collective dysfunction.

However, far from being fiction, dysfunction in a range of public interactions can manifest as poor communication, power plays, conflict, verbal/emotional/physical abuse and lack of respect – among other things. This pattern is rampant, in numerous scenarios, throughout our "better-get-used-to-it" society.

Often feeling powerless or that "nothing will change", many TT citizens may find it easier to keep quiet, existing in a dysfunctional "comfort zone" —that illusory "Paradise" of situations and environments that are toxic and dangerous, yet considered "normal" because they have been "known", accepted and sometimes even celebrated over a period of time as "We Culture".

Is this the "taxi" we want to drive us forward?

Comments

"‘Better get used to it’ syndrome"