Righting a great wrong: UK group works for slavery reparations

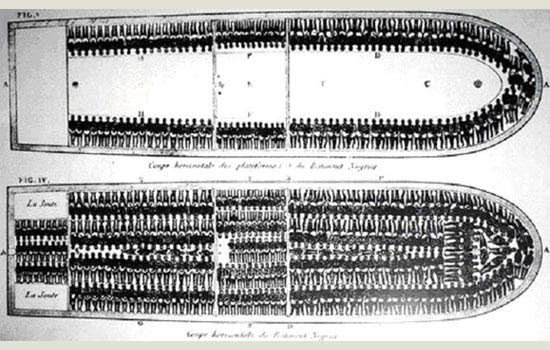

British descendants of people who were involved in and profited from transatlantic slavery plan to contribute funds to those affected and to raise awareness of the historical facts surrounding it.

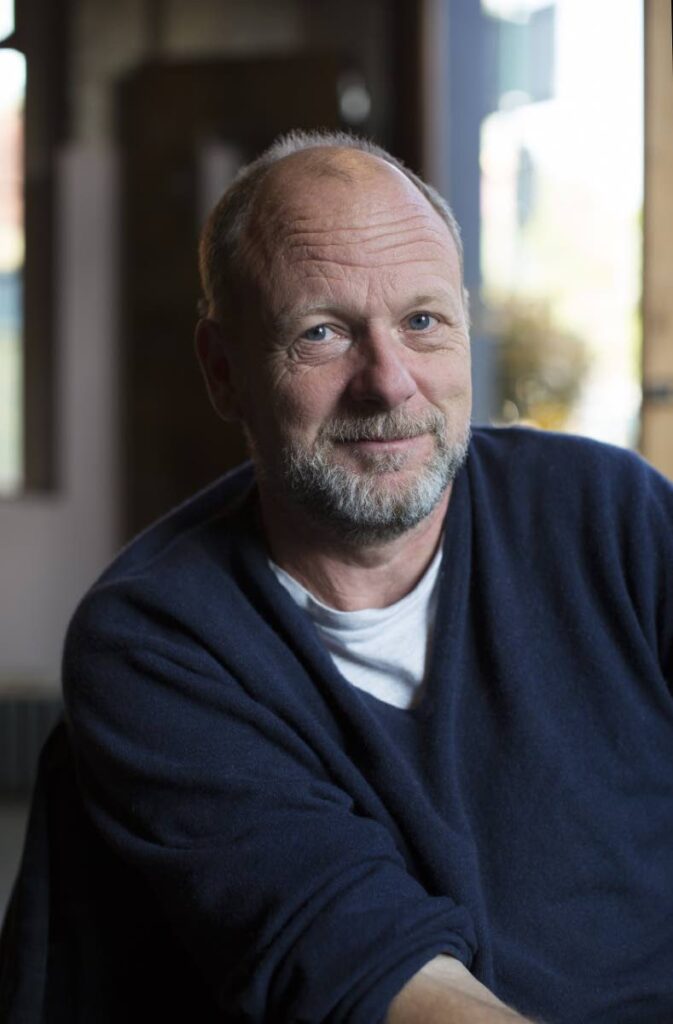

In a phone interview on April 21, a member of the influential group, journalist and writer Alex Renton, explained why the group, Heirs of Slavery, was formed.

Renton wrote in his 2021 book Blood Legacy of his own sickening discovery that from the late eighteenth century his Scots ancestors had owned estates and enslaved people in Tobago (at Bloody Bay) and in Jamaica.

The Heirs of Slavery say, “There are wrongs in today’s world that derive from Britain’s exploitation of African people and their descendants. We believe it’s important to acknowledge this crime against humanity and address its ongoing consequences. We wish to support today’s movements seeking apology, dialogue, reconciliation and reparative justice.”

The group is also encouraging others in a similar position “to consider how personal charitable donations, according to their means, can help the futures of people in the Caribbean and Britain.” But its main purpose, it says, is “to lend our voices as heirs of those involved in the business of slavery to support campaigns for institutional and national reparative justice.”

It supports the Caricom ten-point reparatory justice plan and is calling for dialogue between the British government and other former colonial powers to discuss the plan with Caricom.

It also welcomes moves by British institutions to examine their role in and profit from slavery and their responsibility to the descendants of its millions of victims.

Ignorance is bliss

Renton says of his own experience, “If you ask anyone in the Caribbean, they want an apology first, but people in the UK can’t see why they should apologise in this case. There’s a culture war on this issue, and honest telling is really central to that.”

He himself, he admits, “grew up in ignorance except for (the British MP and abolitionist William) Wilberforce.”

This accords with British history lessons on the topic. As Eric Williams wrote in Capitalism and Slavery, “British historians write almost as if Britain had introduced Negro slavery solely for the satisfaction of abolishing it.” Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807 and nominally granted emancipation in its colonies in 1834.

But in fact, Williams argued, it was to a considerable extent the profits from slavery and the slave trade that funded the Industrial Revolution and made Britain the dominant world power of the day.

Gary Younge, a British journalist of Barbadian ancestry, recently wrote an essay titled: Lest We Remember: How Britain buried its history of slavery.

The essay appears in a section of the UK Guardian newspaper’s website, Cotton Capital, which explores how the paper discovered that in its early days as the Manchester Guardian, it had benefited from the cotton grown by enslaved labour in the US. Manchester was a centre of the cotton and textiles trades. Trinidadian researcher Dr Cassandra Gooptar wrote in the paper about the uncovering of these links. Nine of the 11 men who lent money to the paper’s founder had connections to transatlantic slavery through their commercial interests in the cotton industry.

International action on slavery

In 2018, the Danish government apologised to Ghanaians for Denmark’s role in the slave trade in what was formerly the Gold Coast. Foreign Minister Anders Samuelson said nothing could justify the inhuman treatment meted out to the victims of the trade.

In December, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte offered a formal apology for the Netherlands’ historical role in the slave trade, describing slavery as a crime against humanity. His apology got mixed reactions in the former Dutch Caribbean colonies, however. The Dutch government has recently set up a reparations fund.

Britain: ‘Let’s move on’

The approach of these two countries is in stark contrast to that of Britain.

Renton says in the UK, as well as insufficient understanding of why there should be any apology or reparations for slavery, there is a right-wing backlash against the movement, “to the point where actual untruths are being told and pseudo-history spread.”

So part of the aim of the movement is to educate the British about the facts.

Renton pointed out in a statement from the group, “Britain has never apologised for (slavery), and its after-effects still harm people’s lives in Britain as well as in the Caribbean countries where our ancestors made money.”

In 2015, addressing the Jamaican Parliament, UK Prime Minister David Cameron avoided calls for an apology or reparations, spoke proudly of Britain’s part in abolishing the centuries-long slave trade, and called for the two countries to “move on.”

Last November the government of Barbados said it was considering plans to make a wealthy British MP the first person to pay reparations for his ancestor’s role in slavery. Richard Drax, who still owns an estate on the island, travelled to Barbados to meet PM Mia Mottley, whose government was said to be ready to take legal action if no agreement was reached.

Acknowledging Britain’s role in slavery

Renton explained that the Heirs of Slavery wanted to launch their group before the coronation of King Charles II on May 6.

Earlier this year, Buckingham Palace issued a statement in response to questions from the UK Guardian about British monarchs’ investment in enslaved African people, after the release of a document demonstrating that one of the king’s predecessors owned a stake in a slave-trading company. In early April, Charles responded by indicating, for the first time, royal support for research into these historical links. It’s not clear yet what consequences might follow from the findings of this research.

Richard Atkinson, another member of Heirs of Slavery, said in a statement from the group, “Until the painful legacy of slavery is recognised by the descendants of those who profited from it, there can never be healing.”

David Lascelles, Earl of Harewood, said, “Those of us in this group share a dark history, one that we are endeavouring to be open about in the hope of encouraging dialogue, friendship and reconciliation between all the people whose lives have been affected. We urge other people with a similar history, both individuals and institutions, to join us in speaking out.”

“I joined this group in an attempt to begin to address the appalling ills visited on so many people by my ancestor John Gladstone,” said Charles Gladstone.

Laura Trevelyan wrote in the UK Guardian last month that her family had been absentee “owners” of more than 1,000 enslaved people in Grenada, for whom they had received the equivalent of about £3 million in today’s money. After finding this out in March, she left the BBC that month, after 30 years, to campaign full-time for slavery reparations.

Sir Hilary Beckles, chair of the Caribbean Community’s Reparations Commission, she wrote, “convinced us of the power of an apology and encouraged us to lead by example.” The family wrote a letter apologising to the people of Grenada. Over 40 family members signed it, and seven of them went to Grenada in February to deliver it.

“We hoped we could at least acknowledge the suffering our ancestors had inflicted on Grenadians, and perhaps encourage other families…to do the same. The country’s young prime minister, Dickon Mitchell, graciously thanked us, and said he forgave us.”

The Trevelyans also decided to donate more than £100,000 to education projects in Grenada.

The rest of the group and their families have also made private donations “to tackle poverty, poor education and other issues affecting the descendants of the enslaved in Britain and Caribbean countries.”

They are also talking with British descendants of enslaved people who have experienced racism, poverty and inequality.

“I would like to listen and learn from the descendants of the enslaved to find out what would best help them in their lives today. Please tell us how apology and repair, led by the British nation, should work,” said Robin Wedderburn.

Renton says the group is anxious not to indulge in a form of neo-colonialism by deciding how the Caribbean and members of the diaspora should be compensated. They want to use “the privilege and influence we have inherited” to support movements started by the people who are affected.

Caricom’s ten-point plan for reparatory justice

Caricom has formed a reparations commission to press for compensation from the European countries that perpetrated slavery.

* Full formal apology

* Repatriation

* Indigenous peoples development programme

* Cultural institution

* Addressing the public health crisis

* Illiteracy eradication

* African knowledge programme

* Psychological rehabilitation

* Technology transfer

* Debt cancellation

Signatories to the Heirs of Slavery statement include:

David Lascelles (Earl of Harewood), whose ancestors built Harewood House, Yorkshire, with money from the sugar trade and the slave trade. They received £26,309 in “compensation” in 1835, after emancipation, as part of the £20 million disbursed to former slave owners.

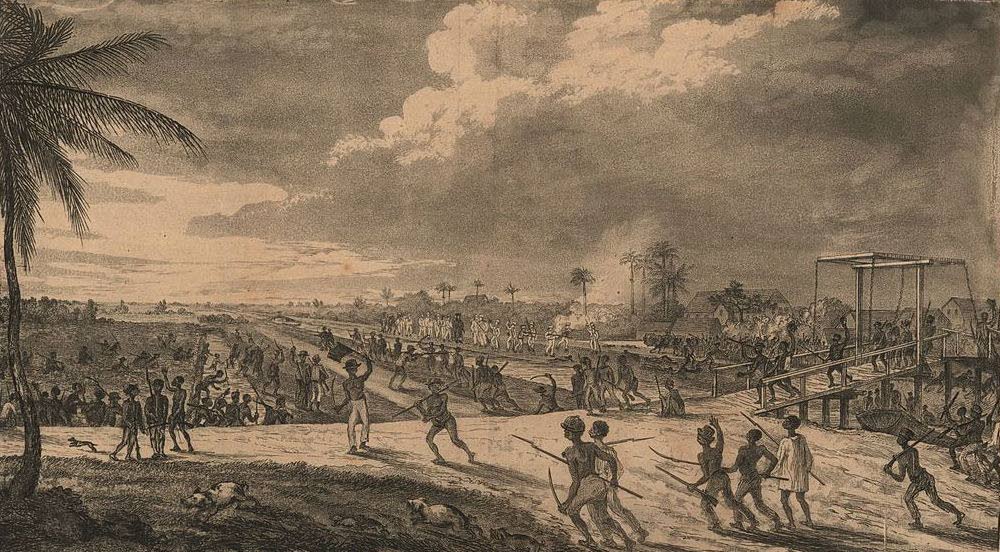

Charles Gladstone’s ancestor John Gladstone owned sugar plantations in Jamaica and what is now Guyana, receiving £106,000 in “compensation” at abolition. The Demerara Uprising of 1823, which involved more than 10,000 enslaved people, was started on one of John Gladstone’s estates by Jack Gladstone, named after the owner.

John’s son William, later UK Prime Minister, made his maiden speech in Parliament against the abolition of slavery.

Richard Atkinson, publisher and author of Mr Atkinson’s Rum Contract, whose ancestors owned or managed numerous sugar estates in Jamaica.

Laura Trevelyan and John Dower’s Trevelyan ancestors in 1835 shared £29,000 as “compensation” after emancipation for 1,004 enslaved people in Grenada.

Rosemary Harrison is a descendant of an eighteenth-century Jamaican attorney general who owned enslaved people as servants.

Robin Wedderburn’s ancestor John Wedderburn, a soldier and assembly member in late eighteenth/early-nineteenth-century Jamaica, owned at least ten plantations and the enslaved people on them.

More on Heirs of Slavery

The group is on Twitter: @heirsofslavery

It has also set up a website at www.heirsofslavery.org where members can be contacted. The website also includes more information and a list of some educational projects and other charities supported by members of the group.

Renton says he had difficulty finding organisations in Tobago to support, and would love to hear from groups there involved in youth educational work.

Judy Raymond is the author of The Colour of Shadows: Images of Caribbean Slavery (Caribbean Studies Press).

Comments

"Righting a great wrong: UK group works for slavery reparations"