Systemic memory loss

The Guardian newspaper in Britain has joined other US and UK entities in researching its historical links to slavery. The result has been available over the last fortnight in a superb series of eight, long, well-researched features by outstanding contributors.

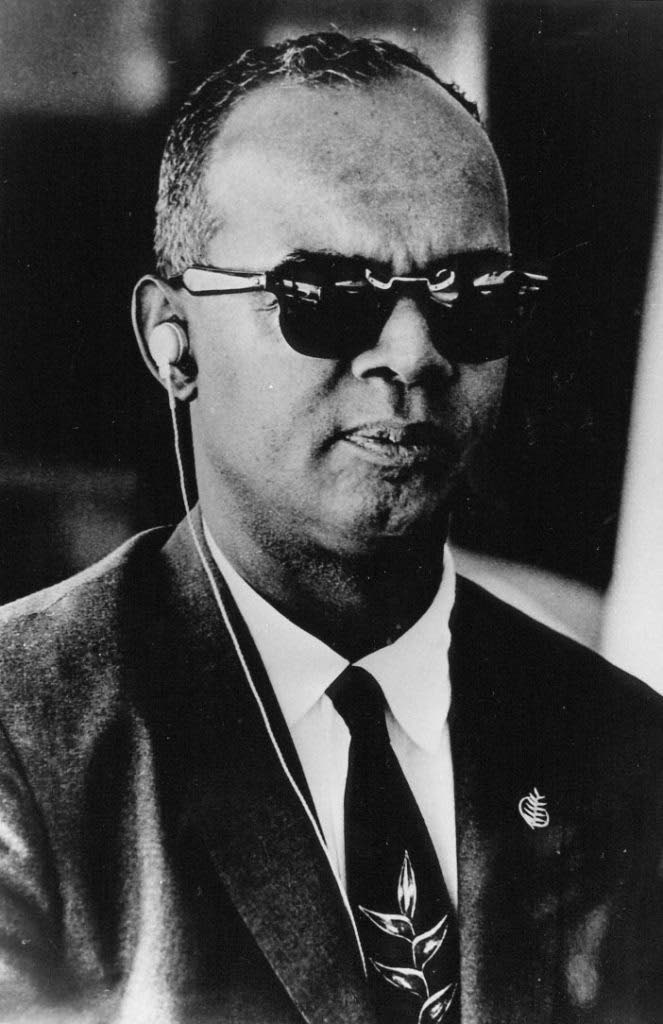

The series offers, too, eight new portraits by leading black artists of radical anti-slavery figures and thinkers, including our own Dr Eric Williams. Poems and short fiction by Caribbean writers including Lisa Allen-Agostini and Anthony Joseph, who will appear in the imminent NGC Bocas Lit Fest (April 28-30), are also part of this special project called Cotton Capital.

Quite apart from the imagination and investment required for such a project, we must commend the paper’s respect for the intelligence of its readers and admire its preparedness to lead the way in the media, uncovering and discussing a critical and protracted period of British history of which few Britons are aware. The focus is Manchester where the paper was founded and which had strong links with the cotton trade but the legacy of slavery in the city and elsewhere in Britain and its former colonies is within the project’s scope too. The killing of George Floyd unleashed an international response to the continued violence against people descended from slaves in the US, principally, but the trade was transatlantic and involved the vast British Empire which spread over Asia, Africa, half of the Americas and Australia. No surprises then that the ripple became a wave.

In the Caribbean, we know that in pre-Independence years, as devout British subjects with British dominion passports, we travelled freely throughout the Empire and fought in WWI and WWII under British command. When the war was over and Britain had to recover we were invited to be part of its reconstruction and the present Caribbean-originated British population derives from that exodus of the 1940s-60s mainly. Well, most British people had no idea because they were taught a sanitised history and their ignorance led to the Windrush debacle a few years ago which ruined the lives of Caribbean people and their descendants who were deemed to be illegal immigrants. There is a consequence, therefore, of withholding the truth or of partial truths. A much more palatable historical account was the role of Britain in the abolition of slavery. To quote Eric Williams, “The British historians wrote almost as if Britain had introduced Negro slavery solely for the satisfaction of abolishing it.” Filling in some of the glaring gaps and linking modern, ordinary Britain with its secret past, must come as a shock for many, after all Bristol and Liverpool as critical ports in the triangular trade have been acknowledged but not Manchester, and certainly not the lasting legacy of that experience.

Cotton Capital illuminates how Manchester’s rise to be the textile capital of the world by the 1830s was the result of global industrialised capitalism underpinned by the structures of colonialism and slavery. The wealth created completely transformed British society and culture, as it did other colonising countries, as sugar and cocoa did. There has been some revisionist disputing of Eric Williams’s theory that enslaved labour and the profits made from slavery drove the Industrial Revolution (Capitalism and Slavery) but this series explains to Guardian readers how it happened. Technology developed in response to the demand created by the supply of commodities grown in the new world, whether it was the cotton gin in 1793 or the coal powered ships and railways to move the goods. The US south was the world’s largest cotton producer and its exports made up 40 per cent of British imports in the 1800s, 50 in the 1810s, and 71 in the 1820s, from zero in 1790. Manchester’s cotton mills went from three to 19 between 1790-1800 and the city never looked back as thousands of workers flooded in.

The Manchester Guardian was started in 1821 by cotton merchant George Philips. He failed to get a share of the 20 million pounds sterling of government compensation for loss of slaves but those who did invested in railways, industry and local institutions, while ex-slaves received nothing. Our former colonial economies continue to struggle with that legacy of extraction and export orientation and also with the psychological, cultural and social effects of the dehumanisation of the slave, which was essential to the success of the enormous enterprise that involved all elements of the colonising societies, including the Church and the monarchy.

Reparations for slavery – as much about acknowledgement as compensation – is a controversial issue. It will not receive popular support without people understanding how we arrived at this juncture. Systemic amnesia is not helpful in that regard. As Gary Younge argues in his excellent essay, national memory loss is political, not a medical condition. National histories are narratives to which nations are committed and the facts are chosen to suit. Europeans at home, to be fair, did not personally witness Empire or slavery so it has been easier to excise the country’s dark past, but it leaves them unsympathetic to current calls for restorative justice. However, those demands will only grow, making initiatives like the Guardian’s very valuable.

Comments

"Systemic memory loss"