War with Prof Rohlehr

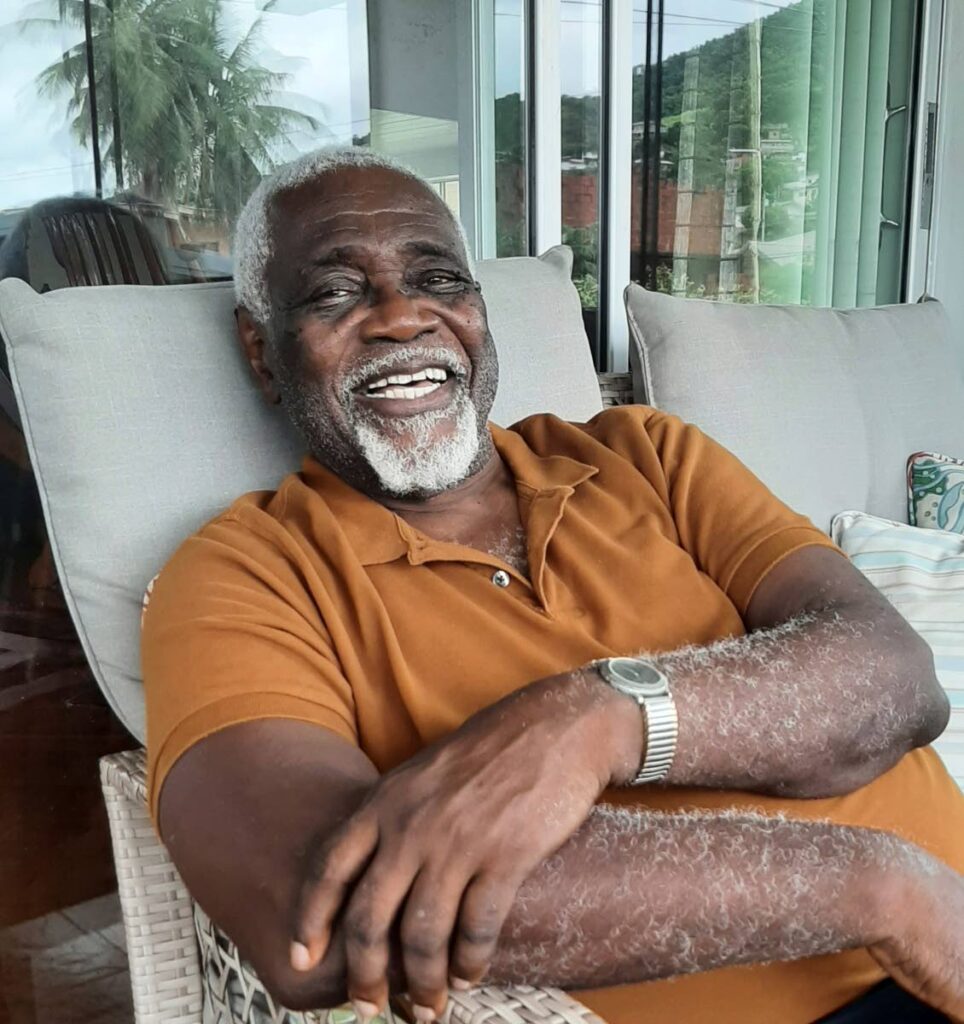

WAYNE KUBLALSINGH

SOME TIME in the mid-1980s, I went to visit Prof Gordon Rohlehr at his Tunapuna home. Out shot his son, Deke, from behind a bush, and attacked me. He shot at me, little squirts of water from a gun, and fled. He was Cowboy and I was Indian.

Dike was just about nine, but tall and spectacled like his father, only straggly instead of bulky. His father was not pleased. He scooted him off roughly, angrily. This spot of anger by my mentor was rare; and though I too raised his hackles, the bonds of love and affection between us never diminished.

Deke probably knew why he was shooting me. I too was playing Cowboy and Indian with his father. Rohlehr was my supervisor for a Master of Philosophy thesis at the University of the West Indies in St Augustine. And we were involved in an intellectual war, one that lasted for seven long years, between 1985 to 1992.

On the recommendation of Rohlehr, I had gotten a scholarship from the university to pursue an MPhil thesis. I wanted to find out how committed Caribbean writers, in particular poets, were committed to Caribbean politics. I valued poets, both writers and singers, who seemed to have some commitment to the polity, the people. Did the poets themselves, the calypsonians, reggae and dub artists, voice poets, the literary poets and novelists see themselves as “socially conscious,” writing with social or political change in mind?

To discover an answer, to discover the Caribbean, I used my scholarship money to travel the Caribbean. To talk to poets. To see their societies. I could not write about people and peoples in abstraction. Or from the garnishing of popular Western media. I had to go and inspect for myself.

I travelled as a student, poor, unknown, itinerant. I saw the Caribbean from bottom-up. I found Guyana, Georgetown, to be mean, shabby, oppressive. Forbes Burnham was in power. Walter Rodney had been assassinated five years before, in 1980. It was the same in Haiti, Jamaica. Haiti was generous but dirt-poor. Jamaica was trying to be generous, the Rastafari brethren I men in Bob Marley’s Trenchtown, despite a politics of dystopia and violence.

Funnily enough, the only societies that were half-free and more generous were Cuba and Martinique.

Cuba was supposed to be a socialist encampment, and whilst the insidious spy games between Washington and Havana created distrust and scheme in social life, the quality of life, basic services were far superior to oil-rich Trinidad.

Martinique, a ward of Paris, a colonial enclave, seemed the most unoppressive and healthy. This was the paradox I discovered. Oppressive and violent “independent” nations, and free and healthy “non-independent” ones.

I had met a number of poets and writers, the effusive and generous Martin Carter in Guyana, John Hearne, Mervyn Morris, Mutabaruka and Jean Breeze in Jamaica, and attended concerts in Cuba (Pablo Milanes in Holguin), and Reggae Sunsplash in Jamaica. I was studying the “literary” poets, Derek Walcott of St Lucia, Edward Kamau Brathwaite of Barbados; and the “oral” poets, Louise Bennett and Bob Marley of Jamaica, and the Mighty Sparrow of Trinidad. My conclusions did not please my supervisor, Prof Rohlehr.

The greatest disagreement was over the Barbadian poet/historian Edward Brathwaite. This poet had promised to make his lines roar like a Caribbean hurricane, not follow the dictates of the inherited colonial British meter, the pentameter. He vowed to break free, from the British, in his poetic language. Write and recite a different rhythm. But isn’t this what Marley, Sparrow, Bennett, Mutabaruka were doing? And communicating, powerfully and dynamically, these popular poets, with their societies?

Rohlehr would not be broached on Brathwaite. Together we had journeyed to the Cayman Islands to attend a symposium. I saw him seated at the front row, armed with his notepad, his tape recorder, all caught and attentive before the saint-like Brathwaite. The disciple before the guru. This disturbed me. Rohlehr was an impressive figure, impressive voice, stature, intellect. To see him sitting there, before his avatar of the vindication of Caribbean voice, transformed into a disciple, surprised me.

Rohlehr rejected my view that the real avatars, the vindicators of Caribbean voice, were the oral poets, Marley, Sparrow, Bennett, and not the literary academic poets. He did not like me deciding what was “real” or “genuine” or “legitimate” and what was not. All had their places. I needed to place them in a continuum. Put them in a line, and show the contexts in which they operated.

So the war went on. I took to more foreign travels, Columbia University in New York and Oxford University in Britain, returned home with post-graduate degrees. The stalemate of ideas then ended. UWI awarded me a MPhil degree.

I was sitting in a restaurant in Puerto Rico with Prof Rohlehr and poet Mervyn Morris. The waitress asked if I wanted my meat “rare.” Rare? What the monkey was rare? Rohlehr interceded to save my blushes, me and my untutored country-bookie self. He ordered for me.

Our relationship was like father and son. Always large, liberal, generous, refreshing in his vision and sympathies. Always kind. Despite my intellectual stubbornness, he never bouffed me. Made me feel small, reduce me, make me his student. He was as rich, warm and comforting as a mother and father to me.

Comments

"War with Prof Rohlehr"