Dealing with a changing climate: Beyond our reach?

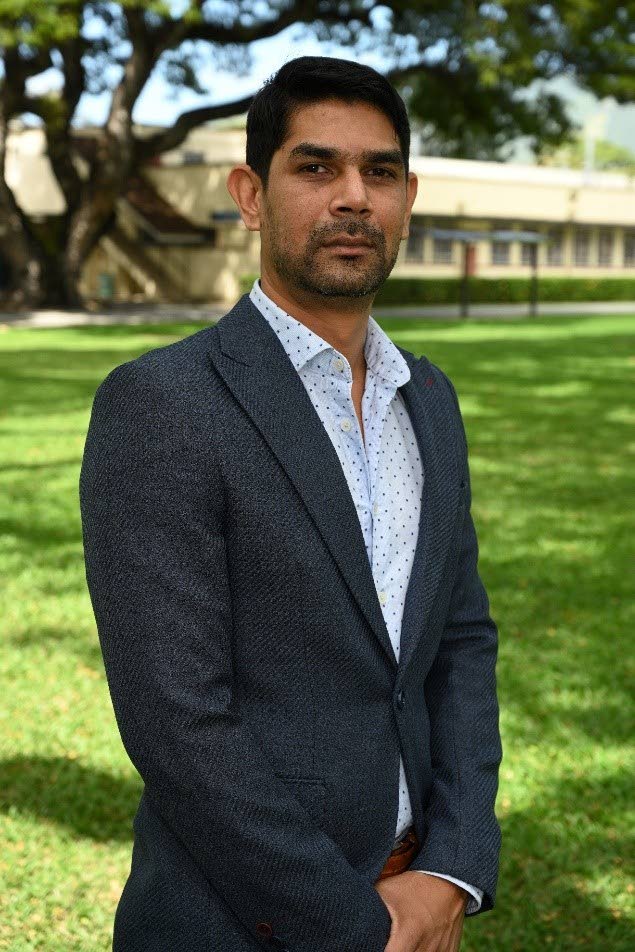

Ronald Roopnarine PhD

The effects of climate change, variability and extremes have become more apparent across TT.

Despite not having been recently exposed to the direct impact of any major natural hazards, climatic extremes, particularly in the form of unprecedented intense rainfall have had devastating impacts on life and livelihoods. Flooding and landslides have become annual occurrences affecting numerous communities, sometimes resulting in catastrophic outcomes.

In 2018, flooding in Central Trinidad affected an estimated 150,000 people. Further, 75 per cent of farmers lost their crops and livestock. People were displaced and businesses and schools interrupted. Similarly, in 2022 several communities across the island suffered the impacts of both flash and riverine flooding, with over 30 flood incidents and 51 landslides, affecting approximately 100,000 people.

Unfortunately, these impacts are likely to increase if appropriate measures are not implemented urgently, as all climate projections/models predict increased occurrences of intense rainfall in future. Incidentally, while we have been focused on intense rainfall events, it would be prudent to ensure that we also prepare for the insidious counterpart – droughts, and extreme temperatures. Dry seasons are expected to become drier across the region, an eventuality we have yet to face and one that could result in devastating outcomes. We must accelerate our adaptation efforts urgently.

Considering the resource constraints, complications attached to governance structures and management instruments, including implementing interventions across multiple sectors and ministries, meaningful adaptation will require significant time, effort, and political will. We have focused too heavily on conventional infrastructural interventions which are costly, unsustainable and require significant state investment.

Often, there is also a disconnect between engineering and nature. This was very apparent recently. Two key examples are the collapsed roadway at Mosquito Creek, South Oropouche and the undermining of the “Manzanilla stretch” which was “reconstructed” less than four years ago after suffering a similar fate.

It should be noted, however, that no engineered intervention can withstand the force of nature in perpetuity, particularly when we ignore the in situ natural phenomena in favour of our developmental ambitions. The same applies to “built” developments, both domestic and commercial, which have increased significantly, particularly on hillsides, altering watershed and hydro-geological dynamics. It is imperative that critical issues like soil types, watershed and hydro-geological characteristics are considered along with the use of nature-based approaches to complement engineered interventions and infrastructural development.

We are a reactive society that manages crisis rather than risk, which compromises our overall ability to develop sustainably in the face of a changing climate. While much of the focus has been on the state to spearhead adaptation and mitigation efforts, and rightly so, we must also accept that we all play a role in this pursuit. At the community level there are opportunities to contribute to the cause that are well within our reach. Nature-Based Solutions (NBs) are becoming more and more accepted as a cost-effective means of improving climate resilience, however, there has been limited uptake locally.

Green infrastructure such as downspout disconnection, rainwater harvesting, rain gardens, planter boxes, bioswales, permeable pavements, green streets and alleys, green parking, green roofs and urban tree canopy and storm water harvesting are worth consideration. Green infrastructure elements can be woven into a community. When green infrastructure systems are installed throughout a community, city or across watersheds, they can provide cleaner air and water, serve as flood and landslide protection, create diverse habitats and aesthetically pleasing green spaces, regulate ambient temperature, and assist with water conservation.

At The UWI, we have been investigating the efficacy of various NBs for flood and landslide mitigation. An example worthy of mention is the use of vetiver grass as a means of slope stabilisation in heavy clay soils. The grass removed approximately 20 per cent more moisture from soils up to a depth of one metre when compared to moisture levels in bare soil.

Ultimately the reduced moisture content limits the potential for slope failure by increasing cohesion between soil particles. We have also done extensive work on flood and landslide risk and can identify communities that are most at risk and thus in need of urgent interventions. Collaborative efforts with state agencies are also on the way towards developing community flood early warning systems and integration of treated wastewater as an alternative water source for agriculture and the environment. We are also “greening” the St Augustine campus to serve as a blueprint both nationally and regionally. An undergraduate major in Disaster Risk Resilience for Agriculture and the Environment will be introduced in September 2023. This programme aims to build technical capacity as it relates to improving resilience to natural hazards and climate change in an uncertain future.

Improving our resilience to climate change is not beyond us, however, we must recognise the gravity of the task and the role of all stakeholders, including the citizenry, in achieving the same. The UWI stands ready to support!

UWI on the ground

A university must be centred in the community, leading on the key issues of the day. Accordingly, the University of the West Indies, (UWI) St Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, presents a public service series where its leading scientists and researchers will address climate and disaster challenges. Today, Dr Ronald Roopnarine, lecturer in Agri-Environmental Disaster Risk Resilience at the Faculty of Agriculture gives tips on managing extreme weather phenomena, using green infrastructure.

Professor Rose-Marie Belle Antoine

Principal, UWI, St Augustine

Comments

"Dealing with a changing climate: Beyond our reach?"