Murders, detection dangers

We could continue beating the escalating murder rate to death, but we must not forget the connected detection rate.

So much so that I felt obliged to write in last week’s column: “Noting the murder rate in 1990 was just 84 with a 69 per cent detection rate, why then did the murder rate rise significantly from 1,181 between 1990 and 2000 with an average detection rate of 64 per cent to a frightening 4,838 murders between 2010 and 2020 with an average detection rate of only 16 per cent?” (Source: TTPS.)

Why this troubling increase in murders and decrease in detection? Naturally, the conviction rates will even be much lower. What are the reliable explanations?

Data between 1990 and 2000 shows that at least 36 per cent of the “murderers” in that period went loose – undetected – with some possibly killing again. It got worse between 2010 and 2020. with 84 per cent of the “murderers” running loose.

What about the victims’ families? (Note, for example, in 2015, the published data shows 420 murders with only 57 (14 per cent) detected. This “detection” rate may well also include some murders from the year or years before 2015. However, the analysis within ten-year periods (eg. 2010-2020) helps smooth this variability.)

Our murder and detection rates need to be put in emergency mode. It is a mental health emergency. (A record 580 so far.) Clearly our police need help, plenty help from inside and outside, locally.

Two things here: (1) As the murder rate rapidly escalates, the pressures on the same investigative units and resources of the police service accordingly increase, thus leading to investigative inefficiency and delays. There is therefore need for rationalisation.

(2) Criticising the police service does present a dilemma. That is, while there is inside corruption and inefficiency, widespread criticisms of police officers tend to demoralise and have Peter paying for Paul. How then do we press for accountability and improved performance?

An early remedial intervention into this security dilemma is to find out where the lines of institutional responsibility lie and what role the police commissioner, minister, government policies, the Police Service Commission, etc, play. We need to find out.

I therefore asked: “Before 2006, police commissioners complained of having responsibility without the required authority. How come then the murder rates rose so significantly and the detection rates decrease so significantly after 2006 when the commissioner got, constitutionally, 'complete powers to appoint, manage and discipline' officers as well as becoming accounting officer?"

In this murder-detection rate disconnect, I also asked: “How come such things continue to get worse after Parliament removed the PM's veto over the commissioner’s appointment? How efficiently and effectively has the constitutionally reformed Police Service Commission functioned in appointing a commissioner and in improving police management and performance after 2006?” Why?

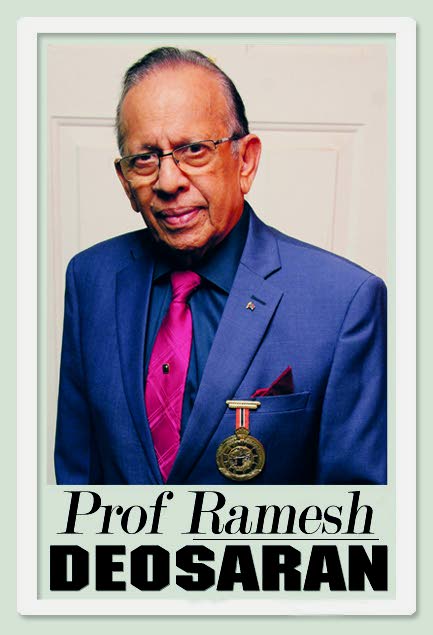

To help energise and institutionalise community policing, a Cabinet-commissioned book produced 42 recommendations (R Deosaran, The Dynamics of Community Policing: Theory, Practice and Evaluation, 2000) including innovations, programming, citizen participation, evaluation, decentralised partnerships, all kick-started by a “national day of community policing” with state-owned television station TTT being effectively utilised. This was used for training programmes in Grenada and St Lucia.

It looks like once again we here have missed another lifeboat.

There is a continuing debate in the criminological literature over whether technology or citizen support is more effective for detecting and prosecuting crime, especially murder and other serious crimes. It would be foolhardy to choose one over the other. Both are useful and in fact supplemental.

The unfortunate fact is that while community policing, in both programmes and implementation. has got promising headlines, police leadership has sidelined these in favour of “more glamorous,” gun-toting law-enforcement.

Community policing in its modernised forms should be strategically integrated within the service in overall recruitment, training, operations and evaluation. The police service is a long way from this, even with the passionate efforts of a few officers like Collis Hazel and Derrick Sharbodie.

The blistering, oft-neglected fact is that without citizens’ support and co-operation, the crime detection rate, prosecution and police investigations will generally suffer. This means that citizens must have trust and confidence in the police and in other government agencies.

The questions increasingly being asked, from president to pauper, are: “Do we have the visionary and accountable leadership, fitting for a troubled democracy? Is there too much spite, too many institutional failures? Do elections help?”

Comments

"Murders, detection dangers"