Days of dark love

NOT SINCE VS Naipaul’s official biography, The World Is What It Is, has the genre of memoir been gifted a book like Ira Mathur’s Love the Dark Days, a work so candid the reader wonders whether it is perhaps too candid.

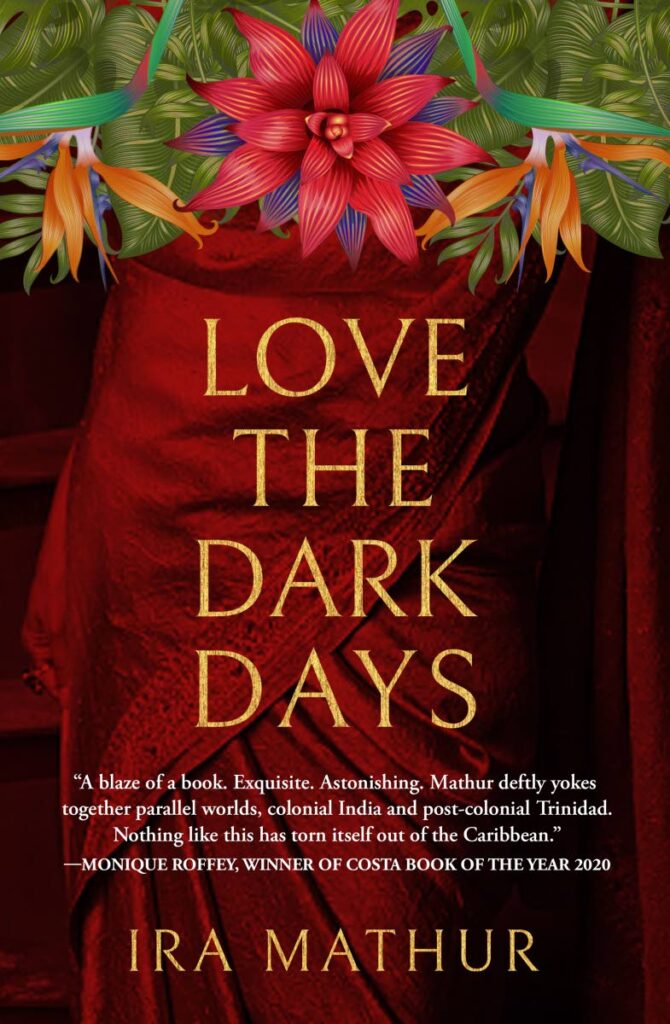

From cover to cover, and at all points in between, the reader of Love the Dark Days is prompted to expect great things. Mathur’s Trini Brit colleagues lead off that process and in procession. The front-cover blurb under the title from Costa prize-winning author Monique Roffey declares Love the Dark Days a “blaze of a book. Exquisite. Astonishing… Nothing like this has torn itself out of the Caribbean.”

On the back cover, Amanda Smyth, author of the excellent Fortune, speaks of Mathur’s memoir “burning through her days, reckless, raw, passionate… An exquisite, compassionate and necessary book.” The poet Vahni (Anthony Ezekiel) Capildeo welcomes Mathur finally putting “something of her beauty, wisdom and pain into print. Here it is. Stranger and more compelling than any fantasy, here we are.”

TT’s leading living writer, Earl Lovelace (relegated to the inside front cover) calls Love the Dark Days “a compelling memoir of the binding power of love and the liberating beauty of forgiveness.”

But Mathur does more in the book to require notice than her well-qualified and well-meaning writer friends’ blurbs.

Apart from one seeming flaw, the book is remarkably well structured (even if the following sentence describing it is not). A tale that begins in India and unfurls across the globe would have to be. The torturous Indian childhood, ignored (at best) by two generations of mothers caring more about one’s springboard into society than one’s bored offspring is connected to the chilling end, the consequences of accepting motherhood that neither one’s parent nor grandparent risked, by the small strands of the grownup, finished and accomplished writer, in St Lucia, in the shadow of the Nobel laureate, Derek Walcott, mashing up his stove and his memory and finally asserting herself… if only in these small links that may go unnoticed and unappreciated. Indeed, the reader has to go back to these interludes at the end of the story to appreciate how well they work to connect the book in the hand of the reader to the voice of the writer. “Remarkable” might be too weak a word; “enviable” might be better.

The only flaw in the structure is the final chapter, which even literally reads like an oversight, since it's titled “chapter 27” – the same number assigned to the chapter immediately preceding.

The book is scathingly honest, even if the most scathed person in the tale is its writer. The reader veers between deep sympathy for the author and, at least once or twice, when the advantage taken of her is so very great, something approaching annoyance – before it dissolves into an appreciation of the skill required to turn this material into something genuine and genuinely readable. Ira Mathur’s major writing, until this memoir, is to be found in her newspaper column, the longest-running one in the Trinidad Guardian. There is where she must have learned the honesty with which she looks at herself and her own families, the one she came from and the one she made. The last chapter of the book should have been, for this reader, the first chapter 27. The second chapter 27 would, to my eye and ear, have been a better prelude, if it had to be included.

It’s relatively small beer, though, when, in the first chapter 27, Mathur reaches heights of honesty that almost worry the reader more than flights of fancy might have, so painful are they to read; how hard it must have been to live them – and then to write about them so painstakingly honestly.

In the end, the quote that does Love the Dark Days most justice is the one from Lovelace: for all the pain and suffering provoked by love deliberately withheld throughout the book itself, the family photographs in the appendix reveal the author to be still directly connected to and appreciative of all the members of her family still living. The love did bind. The reader hopes the forgiveness did free.

Comments

"Days of dark love"