From 60 to 65?

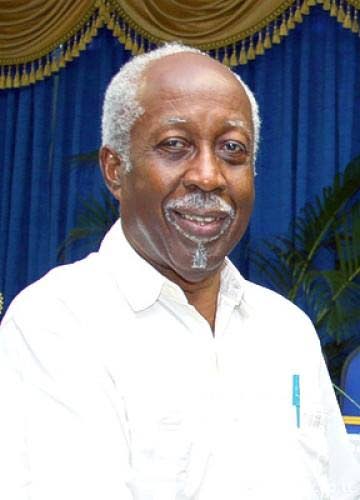

REGINALD DUMAS

ON OCTOBER 14, Attorney General Reginald Armour told the Senate that the Government would be “bringing legislation to (Parliament) intended…to complement the proposed increase of the age of retirement from 60 to 65 years…” On November 4 he told the House that the Government had not yet decided on an age increase; “feedback from stakeholders” was still being solicited. (But then, why give the impression in the first place that the Government had already made up its mind to introduce legislation on the subject?)

There had been mixed reactions from unions to Armour’s October statement. Two promptly said that the age change would benefit their daily-rated worker/members; the sooner such legislation came into effect, the better. Others had different perspectives: they would have to check; the Government was always running off and doing its own thing, but proper public consultation was first needed; young people would have to wait longer for promotional opportunities to come their way; and so on.

I was surprised at the general public silence on Armour’s first statement. I did notice two sentiments, though, which I fully expected: dismay at allegedly “having to wait for five more years before you could retire,” and, echoing at least one union, concern at delays in the upward professional movement of young, or younger, people.

I have three comments to make.

First, it must be stressed that 60 is the age at which a public servant is usually obliged to retire. Section 14 of the Pensions Act states: “The Service Commission may require an officer to retire from the service of Trinidad and Tobago at any time after he attains the age of sixty years or, in special cases, the age of fifty years.”

But this doesn’t mean that in every case you have to work up to the age of 60 in order to receive terminal benefits. Section 15 of the same act provides, inter alia, that in normal circumstances you must have reached the age of 55 to be eligible for pension and gratuity. You can therefore leave before 60 with these benefits. I was one who did, so I speak from personal experience.

Second, the argument about youth is an unsteady one in this society. Launching the 2011 TT census report in February 2013, the minister of planning and sustainable development, Dr Bhoe Tewarie, said this: “In…the decade between 2000 and 2011, the population of (TT) grew by only one-half per cent…(We) have an ageing population. There were significant declines in the age group five-19 with steep declines in ages ten-19.” Has this pattern continued?

Note further. The 1980 census showed that those 65 and over formed 5.57 per cent of the population. The 2020 mid-year estimate of the Central Statistical Office indicates, however, that this group now makes up nearly nine per cent of the population. So the sharp drop in the age cohort five-19, if it has continued, has been accompanied by a sharp rise in the number of those at the other end of the age spectrum.

In addition, our young people, mostly men, have been killing one another at a pretty spectacular rate. Even children not yet five have been liquidated. Emigration is an increasingly attractive option, or imperative. What, I wonder, might the age profile of our society be 40, or even 20, years from now?

Third, this isn’t the first time we’re hearing of government interest in an upward revision of the retirement age. In September 2008 the then Minister of Public Administration, Kennedy Swaratsingh, published a legal notice informing us that the civil service regulations had been amended to allow a permanent secretary or department head who had reached 60 to have his or her service extended by one year with annual renewals for up to five years, ie, up to the age of 65.

The Public Services Association (PSA) took Swaratsingh to court. It argued that his “amendment” was in conflict with the law and, further, that he had not consulted the PSA, as he was legally required to do.

The matter was heard before Justice Judith Jones (now chairman of the Police Service Commission). She ruled in January 2010 that the PSA was entitled to declarations both that Swaratsingh’s “amendment,” and his decision to pass it, were “illegal, ultra vires and contrary to the policy of the Civil Service Act…and the Pensions Act,” and that all actions and proceedings consequent upon the “amendment” were “null and void and of no effect.” Armour may remember the case.

I strongly urge all those concerned with the issue to read the judgment carefully. As for me, I favour a retirement age of 65.

Comments

"From 60 to 65?"