Education system imprisoned

Our education system has not really “collapsed.” As crucial as it is for a democratic culture and equality of opportunity, it remains largely imprisoned by a number of structural and socio-economic restraints.

And while we emphasise examination results, the government seems unable to manage these restraints, resulting in troubling outcomes.

Over the years, the education system itself has been largely trapped, favourably or unfavourably, by the quality of student intake and related socio-economic pressures.

Among the drivers towards such imprisonment are lack of parent-teacher co-operation, school management and leadership, institutional stigma and student expectations, constitutionally-protected Concordat, curriculum deficiencies and socio-economic restraints on equality of opportunity.

-

The recurrent tensions between the Ministry of Education and the indispensable 14,000-member TT Unified Teachers’ Association (TTUTA) should be intelligently healed by having joint meetings at least once a month.

Teachers’ protests against "the education system as a whole” are bad news. True, as Dr Nyan Gadbsy-Dolly declared, “The ministry must govern,” but in this era of popular restlessness in democracies, the exercise of political power must be restrained and strategically partnered.

Of course, covid19-related student absenteeism and missing remedial classes, with 9,000 falling beneath 50 per cent in SEA results, are all very troubling, especially with downstream lower-class consequences.

What aggravates such constraints, however, is the apparent inability of the ministry to effectively activate policies to alleviate, if not eradicate some of them – in particular school infrastructure, delinquency, management and leadership in too many schools.

Government local school boards have not been effective as expected, especially in comparison with the denominational school boards. The middle-level management system of denominational school boards is better able to handle school management and leadership. In government schools, the upward process from principal to supervisor to ministry to Teaching Service Commission seems too centralised, distant and convoluted for effective school management.

What could the ministry do? Rather than improving civility and institutions, the education system has unwittingly contributed the opposite through its outcomes.

Fighting against primary and secondary school competition and deficiencies, many parents, rich and struggling poor, send their children for “private lessons.”

What can the ministry do about this? True, it’s said “some government schools do well” while “some denominational schools don’t do so well.”

However, the comparison fails the proportionality test even when we celebrate the few from Laventille or the children of poor single mothers.

Further, economics intervenes, with many parents sending their children to private schools, and large proportions gaining high places in the SEA. The international private schools allow their high-fee-paying students to graduate and seamlessly enter secondary school or university in either the US or Canada. These “bright” students, together with our job-seeking university graduates, leave never to return.

What can the Ministry of Education do about this class-driven exodus? This loss of talent is unhealthy for our developing country.

Not only this, but our social stratification system gets further overloaded at the bottom, leaving our Ministry of Education a helpless observer. Will the additional $30 million bursaries (600) and vocational courses help? Hopefully, depending on the output data. But it seems we will never know.

Starting with the previous minister, Anthony Garcia and his CEO, Harrilal Seecharan, there was a shutdown of educational data from the ministry on annually-published SEA, CXC, CSEC and CAPE results by schools, district, subject, etc. Mr Seecharan was allowed to declare that whosoever wants such data, if available, could apply “through the Freedom of Information Act.”

Why? This is about accountability, not national security. Can the minister help here? Information is the oxygen of democracy.

Such cross-tabulations should be readily available for researchers, lecturers, policy-makers, the media and concerned taxpayers. UNC Opposition MP Anita Haynes has repeatedly complained about the ministry’s data scarcity. Imagine this, in an age of transparency and accountability. Certainly, this is not the scientific way to run a ministry of education. Surely, we look forward to a positive change under PhD scientists Keith Rowley and Nyan Gadsby-Dolly.

Such data was available in the ministry’s annual reports during former ministers Hazel Manning and Dr Tim Gopeesingh’s tenure.

It seems that the ministry now, regrettably, hides itself by doing what it shouldn’t do and doesn’t do what it should.

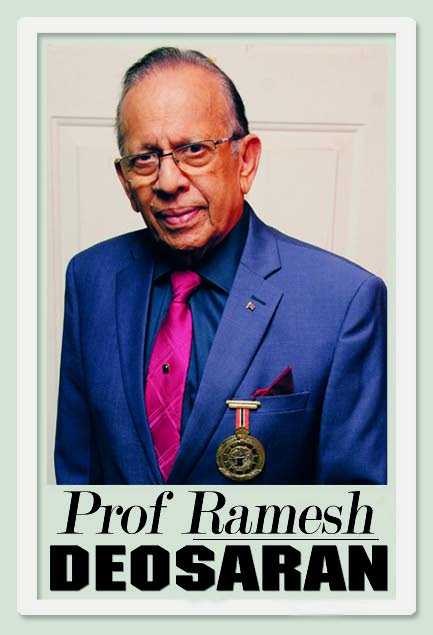

(Prof Deosaran, former member of the Teaching Service Commission, is author of Inequality, Crime and Education in T&T: Removing the Masks.)

Comments

"Education system imprisoned"