The WFH War

BitDepth 1368

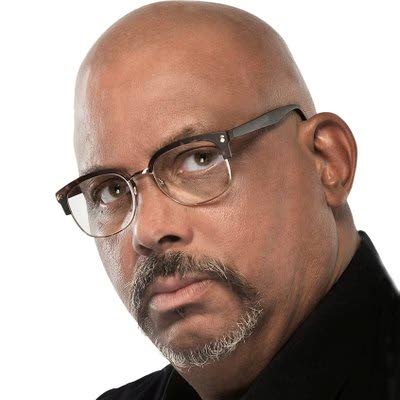

MARK LYNDERSAY

AS RESTRICTIONS have relaxed, old skirmishes are being fought over ground that many thought had been decisively won. Instead of an acceptance of hybrid work and continuing to trust employees to do the tasks assigned to them, there has been a large-scale declaration that it's time to get back to the office.

It's a real Dawn of Justice moment for work from home (WFH), pitting Superman, who shows up at the office (only to duck out ten minutes later, because there's a hurricane somewhere), against Batman, who works from home in a literal man cave with the computer setup we all really want.

Showing up for the man of cubicle's team recently was a real-life superhero of alternative wisdom and reductive reasoning, Malcolm Gladwell.

In an interview with podcaster Stephen Bartlett of Diary of a CEO (https://bit.ly/3Qymeah), he weighed in heavily on the side of going back to work at the office.

"The people who have tended to leave [his business] are the ones who are most socially disconnected from the organisation," Gladwell said.

"[Those] who came into the office the least. It's very hard to feel necessary when you are physically disconnected. We want you to have a feeling of belonging and to feel necessary. We want you to join our team and if you're not here, it's really hard to do that.

"Don't you want to feel part of something? If we don't feel like we are part of something important, what's the point? If it's just a paycheck, what have you reduced your life to?"

Gladwell has been inventively right about many things in his career as an analytical columnist and author, and he's not entirely wrong here either. There are some jobs that really soar on the dynamics of inspired, in-person collaboration, but there is also an aspect of this that reeks of privilege.

I have no doubt that going to work at Pushkin.fm, his podcast and audiobook production company, is an awesome experience, and that the enlightened businesses he visits are also well equipped to inspire their teams.

As sad as Gladwell's impassioned perspective made me, I considered that Gladwell, for all his everyman sense of wonder, is both the boss and a person of means who can shape his workspace to his aspirations.

But what if that isn't the case? What if you don't care for indifferently maintained common bathroom facilities and lunchrooms that are too small and ill-equipped?

What if showing up for work and after parking a mile from where you work and swinging your cramping legs out of the driver's seat, your first inspired thought is to get back in the car and go back home?

Gladwell laments that people of leadership aren't able to effectively explain the value of presence to their employees. But what if that's not what the employer wants?

Curiously, much of the early half of the interview is given over to a thoughtful contemplation of what happiness means at work, but that doesn't factor into any empathetic deliberations about why employees might want WFH.

Most of the employers I've dealt with don't have any illusions that their staff like their jobs, or believe that their tasks should deliver emotional fulfilment.

If these crappy jobs can be done in a comfortable space that just happens to be part of their home, why shouldn't they be allowed to blunt the edge of that daily grind?

Also denied the option of WFH independence are an entire tier of hands-on workers. Anyone who manages atoms, moving packages from one place to another, sliding meals across a counter or shovelling tar onto a road that's recently been dug up again by WASA can't work from home and will face one more social distinction between their work and that of blue-collar workers.

The situation is even more nuanced for neurodiverse workers who found new freedom in WFH from the social and physical challenges of a shared workspace outside their control.

Over two years of pandemic restrictions they carved out environments that made them happy, allowed them more flexibility to care for loved ones and for themselves and enabled a new way of thinking about getting work done.

It isn't a clear win for anyone. This study (https://bit.ly/3As6P5T) found that people working at home did the same amount of work but took 30 per cent longer to do it.

But we've been working in offices for more than two centuries. It's crazy to think that two years of forced WFH will deliver an unassailable path forward.

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"The WFH War"