Pearl Marshall: Trini who made history as a black flight attendant

CHRISTOPHER NATHAN

The memory of BWIA International Airways Corporation lives on in a social media group with a membership of over 100 former airline pursers and senior flight attendants.

Adamant that the beloved BWEE is too precious to fade away, the group has committed to spreading news about the dissolved carrier to the world of aviation.

These efforts received a boost when I came across evidence that one of our colleagues, Pearl Lydia Marshall (later Marshall-Beard), had been the world’s first flight attendant of African descent.

Unfortunately, Marshall’s accomplishment is not mentioned in academic journals or aviation history publications. The accolade of “world’s first black flight attendant” goes to a member of Cameroon’s royal family, Princess Leopoldine Emma Doualla Bell Smith, who in 1957 began training with a French/African airline – Union Aeromaritime de Transport/Union de Transports Aeriens. She later transferred to Air Afrique, where she became chief hostess.

Ruth Carol Taylor is recorded as the first African American air hostess, after an historic flight on February 11, 1958 on Mohawk Airlines from Ithaca Thompkins Regional Airport to New York.

In addition to my research at the National Archives and the Heritage Library, jeweller Gillian Bishop connected me with Marshall’s daughter Lisa, who lives in San Francisco, and she connected some dots. She also provided newspaper clippings and some family background about her mother’s flying career.

Marshall’s historic journey began in 1950: encouraged by Sir Hugh Wooding, former mayor of Port of Spain and later chief justice, and Beryl Mc Burnie, founder of the Little Carib Theatre, she entered the previously all-white Jaycees Carnival Queen Show in 1950 and placed first runner-up to Marion Halfhide-Borde.

Ironically, one excuse she later received from Lady Wooding for not winning was that the first prize was a trip to New York, but the judges unanimously decided: “New York was not ready for a black queen.”

During that period, the Trinidad Carnival Queen shows were an upper-crust, high-profile pageant; the contestants were sponsored by major corporations such as Pan American Airways, Trinidad Publishing Co Ltd, Agostini Bros Ltd, JT Johnston and Furness Withy.

Unable to secure a sponsor, Marshall competed as Miss Little Carib, since she was one of Mc Burnie’s dancers. But insufficient financial support and no sponsors meant little money for the designer wardrobes expensive shoes and jewellery of the other contestants, so it must have seemed like a Cinderella movie script to the statuesque five-foot-seven-and-a-half beauty from San Fernando. Her first outfit was casual shorts and a simple blouse, the second a three-quarter-length, grape-coloured evening dress, which she had to wear for the formal evening-wear segment.

Though she did not win, the experience clearly boosted her confidence and in 1955 she applied to join BWIA's Inflight Services Department, up until then dominated by white air hostesses.

On January 23, 1956, Marshall was offered a job at BWIA and so entered the history books as the first flight attendant of African descent hired by an international airline. It is clear that her selection was a calculated decision by Sir Hugh and the rest of the BWIA board.

After ten years working at Radio Trinidad, Marshall was a sophisticated, experienced professional woman. BWIA Inflight co-worker Angela Inniss recalls seeing Marshall riding her bicycle along Marli Street on mornings on her way to work; she left Radio Trinidad as a senior member of the traffic department.

Sir Hugh was at the time chairman of Radio Trinidad and also deputy chairman of BWIA International; he had reportedly instructed the board to introduce “a new ethnic group to the carrier,” according to a (local) People magazine story of July 1980, and he suggested Marshall as the guinea pig.

Marshall reflected that Sir Hugh “was such a lovely man in every way, I found it difficult to say no; even though it meant a considerable cut in my income.”

There are reports that white BWIA hostesses refused to train her onboard the Vickers Viscount aircraft when she completed initial emergency procedures and ground training; the white stewardesses were reportedly prepared to risk losing their jobs over it.

Eventually a Barbadian senior stewardess, Pauline Fitzgerald, agreed to train her on the Viscount aircraft which would fly her into history.

Marshall later told reporters at a press conference: “BWIA had been their private domain. The stewardesses were from all over the Caribbean and they were all white, but it was the French Creoles from Trinidad, though, who were kicking up all the fuss.

"I had the kind of personality that was needed; I wasn’t just simply a token black for the airline to parade out and I was concerned with doing a good job; ensuring that the confidence placed in me was well worth the trouble.

"I did not think of my recruitment as a personal victory, it was not until I travelled to the US in August 1957 that I realised what an achievement it was.”

Marshall remembered passengers boarding her first long-haul flight to Jamaica from Trinidad in April 1956. The crews referred to this flight as “the milk run,” because the Dakota DC-3 had to make so many transit stops on the way to Kingston: (Grenada, Barbados, St Lucia, Antigua, Puerto Rico).

“The fact that there was a black stewardess on board was completely new to them, you could see them literally take a step back at the cabin door. Most of the white passengers were aloof, but I had been sent to do a job to the best of my abilities and take care of all my passengers. I was always respectful and I never crossed the line…I hate rudeness in anyone.”

Reporter "BG" interviewed Marshall at the airport in Kingston after the flight and filed a report for a Jamaican newspaper that was headlined: A Fine West Indian Girl.

It described her as a "stately tall girl with the flashing eyes and trim figure," and said she had been wolf-whistled "with all the appreciative feelings of a male with a discerning eye" and had acknowledged "the compliment" as she reported after her first big flight.

"In a way," the story went on, "it was an historic occasion for she is the first truly West Indian girl to be appointed by the airlines as an air hostess." Marshall reportedly confessed to being “a little excited” at the trip and "the fun of her new job," which had begun with a shorter trip to what was then British Guiana.

Marshall was "as trim as the trimmest, her airforce-blue, tropical coat and skirt fitted neatly, her white, striped, nylon blouse was as white as the sea foam and her black close-cropped hair was tucked away beneath the jaunty, quilted cap which was slightly tilted to the right. She was an example of good grooming – from the winged insignia on the cap to the polished tips of her navy, court shoes."

By August 1957, BWIA had seven black stewardesses, of whom Marshall was the most senior. After a year flying within the region, she was deemed ready for a flight to New York.

Here she was the junior stewardess, and remembered looking out from the aft crew jump-seat for landing, though the rear cabin windows, and seeing what appeared to be hundreds of people waving madly. She thought they had come to the airport to see the modern jet (BWIA's Viscount aircraft was the first turbine-powered jet to land in New York).

But as the four-engine plane taxied to a halt, Wooding asked Marshall to remain on board with him until the passengers and crew had disembarked. She didn't expect the boisterous reception she received when she stepped out of the cabin door and nervously faced cheering, clapping, ecstatic crowds.

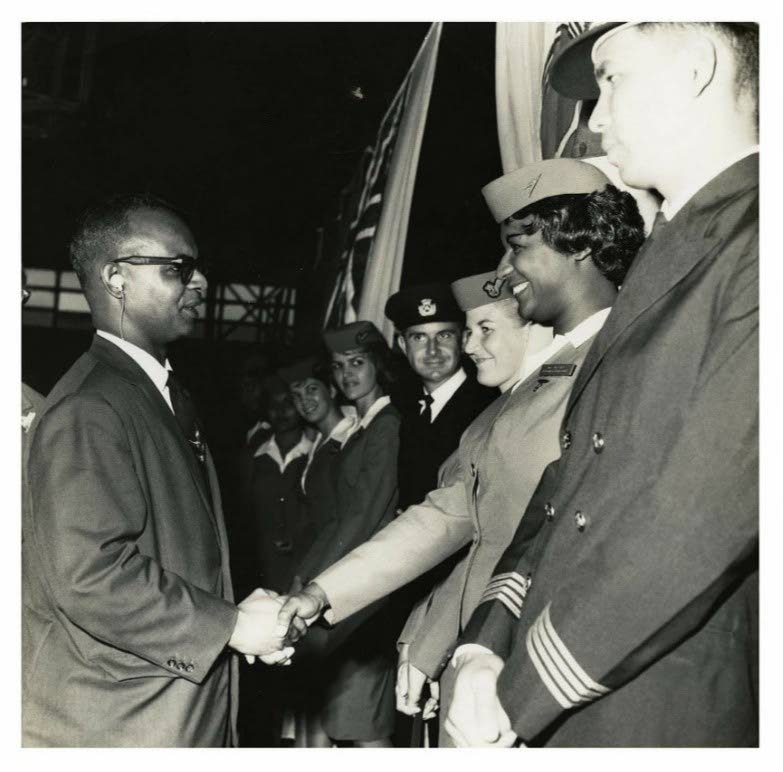

Idlewild’s airfield and arrival area were reportedly packed with over 2,000 curious New Yorkers, all seeming to be reaching out to shake her hand; there were newspaper reporters, photographers and television crews with bright lights aimed at her to record the historic arrival. Also on hand was a delegation headed by Edward Lewis, executive director of the Urban League of Greater New York.

The unexpected commotion caused New York airport officials to deny interviews and photographs and Marshall was whisked away to her hotel in a waiting car.

A press conference was arranged for the following day. There she expressed surprise that her arrival had created so much interest, adding that she was not familiar with the long-time efforts by the Urban League and other activist groups to get American airlines to hire black pilots and hostesses.

Asked if she realised the significance of her arrival at Idlewild, she told reporters: “Not at all, my coming here is just a normal course of development on the job. I had first served on the shorter flights, then longer in the Caribbean and then I became eligible for an international flight.

"I grew up in a country where we go to school with whites, we have white friends; segregation doesn’t exist.”

She also made clear later: “I was chosen because I had certain qualities needed for an introduction as the first black person in an international airline service.

"I think it was time to integrate the airline, especially the cabin services. My being hired was important to the American people because they were struggling for racial equality. Around that time there was a black American nurse fighting a case in court against an American airline which did not want to hire her because she was black…my situation I believe strengthened her case.”

Looking back, Marshall told Newsday journalist Angela Pidduck: “All the black publications were there and what seemed like hundreds of microphones were pushed in my face. They came out of curiosity; the interest of the black American was that I was somebody who was their colour. Imagine they are fighting for equality and there it is – this big jet lands and out comes a black woman.

"To them I was sort of like a messiah; they were just fighting to find a niche for themselves as black people and so they really appreciated my coming there.”

On April 20, 1958, Princess Margaret arrived in the colony of TT to officiate at the inauguration of the West Indian Federal Parliament on behalf of the queen. BWIA selected three stewardesses to fly on the princess's air tour of the islands, and Marshall was chosen, along with Margaret Deveaux and Palma Chow Quan, to highlight the diversity of BWIA’s Inflight Department.

After a five-year stint, Marshall quit flying to accept a promotion as airport representative for BWIA at John F Kennedy International Airport. There she often acted as intermediary between the US Customs and Immigration and newly arrived West Indian immigrants.

She recalled suffering racial discrimination in New York: taking a bus one day, loaded down with parcels, she plunked herself down on the first available seat, right at the front of the bus. A white man sitting opposite mumbled: “Your type do not belong at the front, get to the back!” That attempt at intimidation continued for the entire journey but she politely, completely ignored him.

Marshall returned to Trinidad in the early 1960s, as the government had created a special protocol officer position at the spanking new Piarco International Airport Terminal for her to handle arriving and departing VIPs. She was appointed to BWIA’s board, making her its first female director (1985-1987).

The daughter of James Marshall, Pearl had three sisters: Thelma, Leola and Yvonne. She was educated at the San Fernando Government High School. She married Eugene Beard and they had two children, Lisa and Michael. She died peacefully on May 21, 2006 at her home in New Yalta, Diego Martin.

Comments

"Pearl Marshall: Trini who made history as a black flight attendant"