Answers from a marine biologist

So you are thinking of studying marine science? Dr Anjani Ganase shares some of her reasons for becoming a marine biologist.

Why get into marine biology?

The marine world was accessible and fascinating, growing up on a small island. Trinidad and Tobago has more exposure to the ocean than most other places we think about. Small island states make up a population of about 63 million people or less than one percent of the global population. The ecology of islands is closely tied to the ocean. Growing up, I was able to hike through the northern range and follow rivers leading to the ocean. I spent most of my time at beaches with my head underwater. My parents made sure that I learned how to swim. My grandfather was a fisherman in his spare time; he would take me snorkelling Down De Islands.

What to study in high school, and where to go to university

I was interested in sciences at school and did Math, Biology and Physics. However, I met many marine scientists who only got into marine science later in their studies and transitioned from other fields, such as business and languages. These other skills helped when for project planning and working in other countries. I did an undergraduate degree in marine biology at the Florida Institute of Technology. Here I realised that the foundation of marine biology is in the invisible. Marine micro-organisms are the cogs that keep the ocean food chain churning. I did my master’s at the University of Amsterdam, Netherlands, followed by a PhD at the University of Queensland, Australia. Graduate work provided practical learning about marine research, along with valuable mentorship. Having good mentors to guide your next steps will shape your career as a marine scientist. I’ve been fortunate to have mentors who gave me the opportunity work on their research projects and encouraged learning new skills – lab work, statistical programmes, computer languages, driving a boat.

Is diving essential for a marine biologist

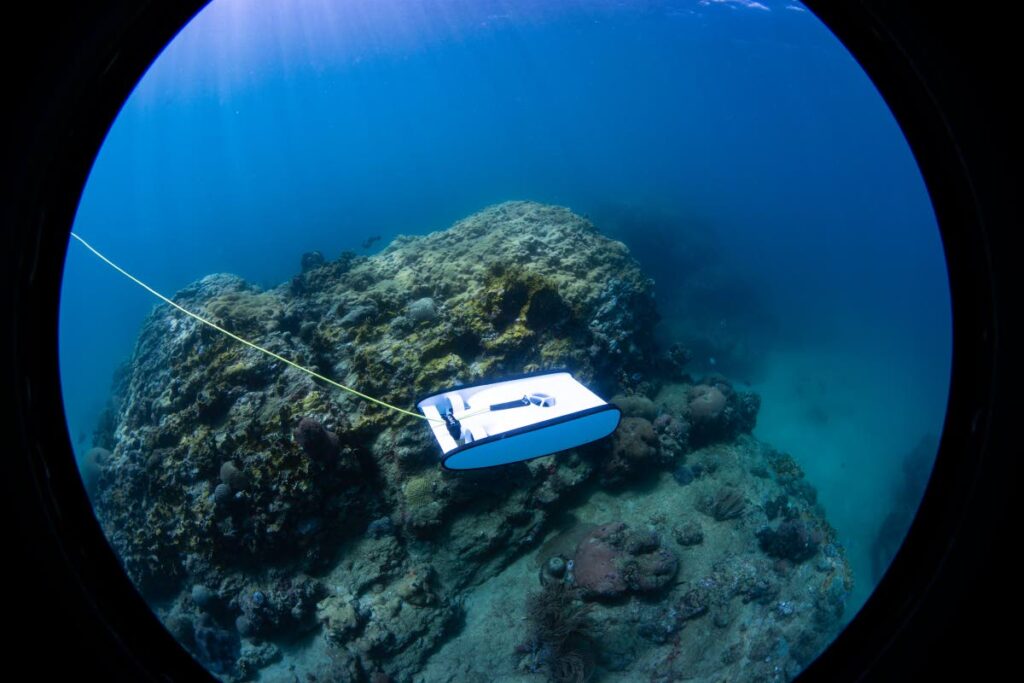

While learning how to dive is one way to get to know the ocean environment, it is not essential. There are many marine environments – mangrove wetlands, seagrass meadows – that do not require diving to study. You can experience the deepsea environment that is beyond our diving limits using remotely-operated vehicles and submersibles. It is essential to learn how to swim, as marine biology requires work in the water.

Greatest ocean encounter

There are many, but my most memorable was having a whale shark swim over my buddy and me during a dive in Indonesia. I have been fortunate to encounter dolphins, sharks, mantas, but I had given up hope for a whale shark. It was at least 25 feet, moving gracefully through the shallow waters and there were many small fish swimming or bow riding around its mouth and body.

Worst experience in the ocean

The worst experience is associated with the ocean itself. There is nothing you can do when ocean currents carry you away. I have experienced currents strong enough to ship you around an island and drag you deeper, even here in Tobago where divers can experience some of the gnarliest currents. During these experiences, it is important to remember your training, keep calm, breathe and equalise your ears.

How much do you get paid

For most marine biologists, money isn’t the reason to go into this field. Marine scientists are thalassophiles (we love the sea) and are attracted to be able to experience the ocean. Salaries depend on where in the world you work, the field of interest, as well as the job. Salary should not be the most important aspect of your job.

Jobs for people studying marine science

The marine world requires biologists, engineers, chemists and every other scientist similar to the land. In Trinidad and Tobago, interest in the ocean and fields related to research and development is slowly awakening. Many marine conservationists and enthusiasts often have to develop their own niche and create their own business or connect with local universities, NGOs, and research institutes. Internationally, marine experts specialising in chemistry, microbiology and aquaculture are in demand, and work in companies interested in water quality and mariculture. There are also conservation positions with national marine parks and regional and international NGOs. People interested in marine science should have regional and international learning experiences.

Daily routine of a marine biologist

Work with marine biology or science is often research-oriented, whether is it to understand environmental impact from coastal development (eg construction of a jetty) or exploring never seen deep-sea habitats. Scientists must know how to plan, budget, and execute projects to answer specific research questions.

Marine biology research fields span the length and depth of the ocean and considering that Trinidad and Tobago is responsible for ocean acreage 15 times the combined land masses of both islands, there is lots to learn and discover in our ocean backyard. To develop projects, a lot of time is spent reviewing scientific literature to find out what other studies exist in other locations, or on different species to help refine your question and maximise your research success.

Another crucial part is connecting with experts in the specific areas of interest for input, and even collaborating depending on the skills needed to conduct the research followed by external review of the process. Working in the marine environment is very expensive – boat rentals, diving equipment – so we want to make sure that we plan properly. The easier part might be the fieldwork.

Time spent in the water, or diving

Most coral reef scientists will conduct one or two major diving expeditions a year to collect essential data, but the time spent working in the field can vary considerably from weeks to months. Fieldwork and diving can be intense as we are limited by the amount of time we can spend underwater, but many marine biologists do spend a lot of time underwater. We often carry tools, such as underwater cameras, dive slates to assist in data recording. We sometimes leave recording material underwater (cameras, data loggers, trackers) and return to collect, hoping that we always find them because anything built to survive in seawater tends to be expensive.

On diving expeditions, most evenings are spent processing samples and saving all the information collected during our time underwater then prepping for the next day of work. Working in the field can be long and arduous at times, but also incredibly rewarding because of the chance encounters we have underwater. Time spent in the field collecting data, often incurs longer time spent behind a computer crunching the numbers and reporting outcomes. Many marine scientists dive to collect samples for DNA sequencing/ lab analysis or tank experiments.

Favourite place to dive

Far Northern Great Barrier Reef, Australia offers the best diving I have ever experienced. This stretch of the Great Barrier occurs on the most northern tropical tip of the Australian east coast away from any major cities. The coral reefs were pristine and teeming with life including lots of big fish and sharks who were curious about us. We would dive reefs adjacent to Raine Island a sand cay with the highest density of nesting green turtles in the world; we would see hundreds in a single dive. Nowhere else in the world have I seen coral reefs with so much life. To have seen these reefs before the desecration by climate change was worthwhile.

Unfortunately, many of those reefs suffered severe coral bleaching in the years after I dived. It was sad to see such loss of coral and other marine life because of the coral bleaching. As a marine scientist, I must now be an advocate for these precious but vulnerable places in the world.

Comments

"Answers from a marine biologist"