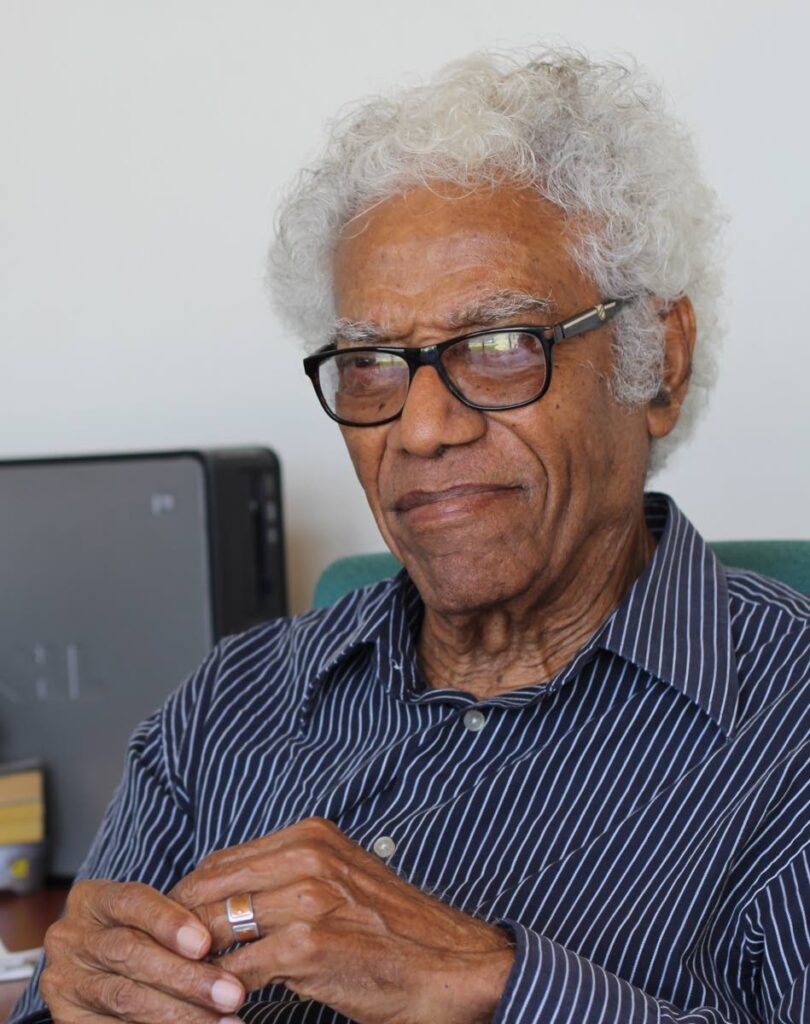

George Lamming’s spell

WHEN THE time came in 1960 for the great Barbadian writer George Lamming to turn to non-fiction, he went right to the source of the language he had inherited: Shakespeare.

The Pleasures of Exile opens with an analysis of The Tempest, covering the dangerous tension between the white magician Prospero and his slave Caliban as they coexist on an island.

“Caliban is his convert, colonised by language, and excluded by language,” Mr Lamming observed. “Exiled from his gods, exiled from his nature, exiled from his own name!

“Yet, Prospero is afraid of Caliban. He is afraid because he knows that his encounter with Caliban is, largely, his encounter with himself.”

This spellbinding fusion of literary criticism with social theory was emblematic of Mr Lamming’s lifelong approach, in which he laid bare the anatomy of a world shaped by empire and its aftermath, a world populated with antinomies that challenge us to see nuance and complexity at play in the forces around us.

In books such as the novels In the Castle of My Skin, The Emigrants and Of Age and Innocence, Mr Lamming went on to chart a dialectic that migrates from what he once called the “tragic innocence” of the Windrush Generation who believed England was a “Motherland” to a more mature notion of self-worth.

“Dream was for me the foundation of all reality,” he said in a remarkable coda to his early work in 2002. “I decided to go home and stay there.”

But Mr Lamming, who died on Sunday just days shy of turning 95, was also unafraid to grapple with divisions in his homeland. For instance, his was a perspective that troubled the idea that the struggle of self-definition for Caribbean states ended with independence.

“The interdependence of countries that characterises today’s world does not allow for the exercise of sovereignty,” he said in 1993 in remarks that could have well been made this week. “You can be independent without exercising sovereignty.”

Instead, Mr Lamming presented a dream even more radical than has sometimes been ascribed to him, one that, perhaps in kinship with writers like Wilson Harris, placed even greater faith in the imagination itself to shape new paths.

“I am a direct descendant of slaves, too near to the actual enterprise to believe that its echoes are over with the reign of emancipation,” he noted in The Pleasures of Exile. “Moreover, I am a direct descendant of Prospero using his legacy of language – not to curse our meeting – but to push it further…to a future which is colonised by our acts in this moment, but which must always remain open.”

It is this openness that is the key to unlocking so much of Mr Lamming’s work, and so much else.

Comments

"George Lamming’s spell"