The crucifixion and development

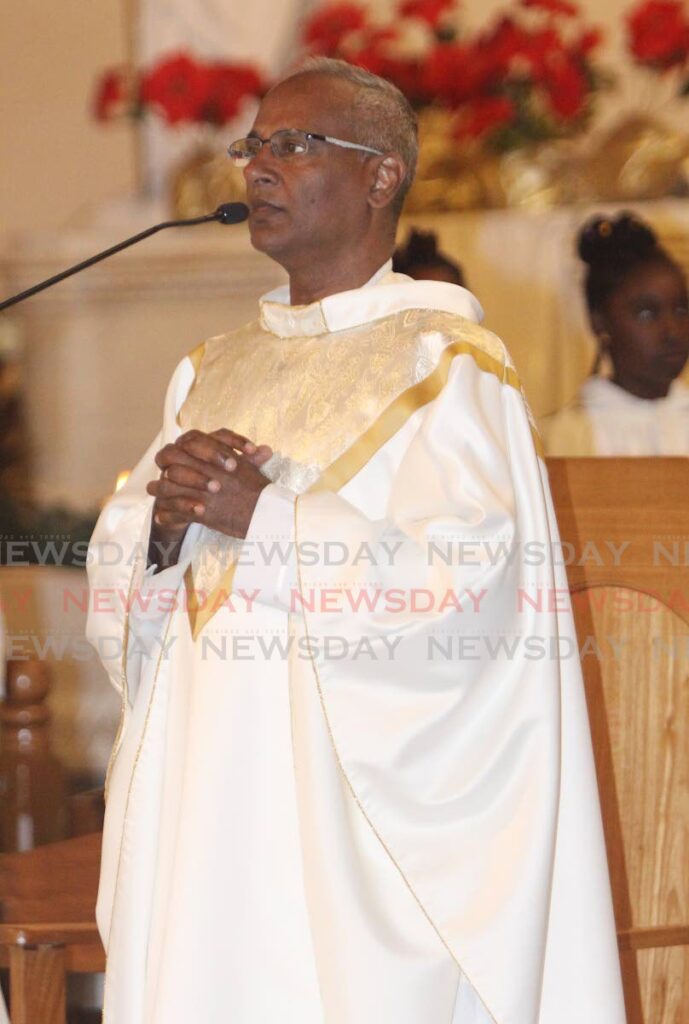

FR MARTIN SIRJU

WE ARE in Holy Week, the holiest time for many Christian denominations. We think at this time of Jesus’s suffering, death and resurrection which form the bedrock of Christian faith. If the resurrection did not happen going to church is a waste of time. Being convinced of that is more a matter of faith than putting the historical pieces together.

What did Jesus die for? To pay for the sins of humanity, to ransom us from the devil, his Father foreordained it are a few of many answers that have been given through the centuries. Another answer, a more modern one, is to secure integral human development, at whatever price.

The key to unravelling this developmental claim is the metaphor Jesus chose to describe his dream – basileia – sometimes translated “kingdom” or more recently “reign of God” or “rule of God,” both of which I find unappealing as they don’t convey energy or excitement. You can rile up people over a kingdom, not over a reign. Try saying, “For thine is the reign and the power and the glory.” It falls flat.

Jesus himself does not deny being a king and says quite explicitly his kingdom is not of this kind (Jn 18:36). This is quite unlike what we hear most of the time. We hear about “church,” but it is only mentioned three times by Jesus, all in Matthew’s gospel. More often Jesus speaks of the kingdom – a more expansive term and one that eludes definition but not description.

He always says “the kingdom of God is like…” In Jn 18:37 he links the kingdom to truth. Speaking truth to power – people always get killed for that one. This Holy Week began with a politically subversive act – a peasant, apocalyptic preacher entering Jerusalem on a donkey. This customary motif is normally associated with a king entering the city after victory.

Everything is turned upside down – a peasant not a king; a battle yet to be won not a victory; a donkey not a horse; the power of truth not worldly power. Jesus was dead long before Calvary and he alone knew that most. It is the utter loneliness of men and women who know they will die because of the double standards they are about to expose. I think particularly of investigative journalists and human rights advocates – the unsung saints.

While all the different theories of salvation have merit, including Jesus died for love of us, that he died in the service of integral human development puts a different twist on things. It moves from the church into the world of politics, big business, economics, communications, culture, etc, because that is where the gospel leads.

If love is real it dares to confront the truth and because of this it becomes subversive as it did in South Africa, in the Civil Rights Movement in America, in the liberation theology of Latin America and in the 1970 Black Power Revolution here. My intention is not to make the mistake many scholars make, turning Jesus into a kind of political hero, military subversive or social reformer.

At the heart of his struggle was not a humanism but a transcendental humanism – he was passionate about what God wanted His world to look like. Religion meant the world to him because the best in his religion envisioned “a new Heaven and a new Earth” for humanity.

In many ways TT is a cruel society – high levels of domestic abuse; the failure to educate large masses of young men, these in turn with no hope turning to crime only in turn to be brutalised by police who must be seen as tough on crime; blatant prejudice based on race and class; a justice system that does not work and cannot work for those who need it most as witnesses are systematically and heartlessly eliminated; the veneer of religious respectability; not to mention the wasting of billions in oil-gas revenue due to mismanagement, over-subsidising and lack of investment.

The world and church would be a much better place if there were more David Abdulahs in it, because unlike most he has, if I may dare say, a Christian social conscience. It is no secret that the corridors of power in this country are filled with Christians, especially Catholics and Anglicans. What is that saying to us in this Holy Week? Are we really working hard enough, especially the Christian professional elite, to make this country look like what it ought to be – a sign of the Kingdom in our midst?

We can start with respect and justice. We cannot seem to carry on humane conversations anymore. Everyone is so angry, so emotionally volatile. And for all this talk on love of which I am fed up, I will settle for Cornel West: “Justice is what love looks like in public.”

I hope this Holy Week we remember not only our personal sins, but our systemic ones, for which that first century Palestinian preacher was crucified.

Fr Martin Sirju is the vicar general of the Archdiocese of Port of Spain and Cathedral administrator

Comments

"The crucifixion and development"