Building a nation with books for children

DARA E HEALY

A SEVEN-YEAR-OLD in Haiti is trapped under his house after it collapsed during an earthquake. As he lies there, he remembers the fun times he shared with his family, like flying kites and playing with his sister.

In St Thomas, a little girl struggles with being bullied while trying to understand her sexuality.

Meanwhile, a girl from Cuba tells stories of the wisdom of her grandmother and her life growing up in Havana.

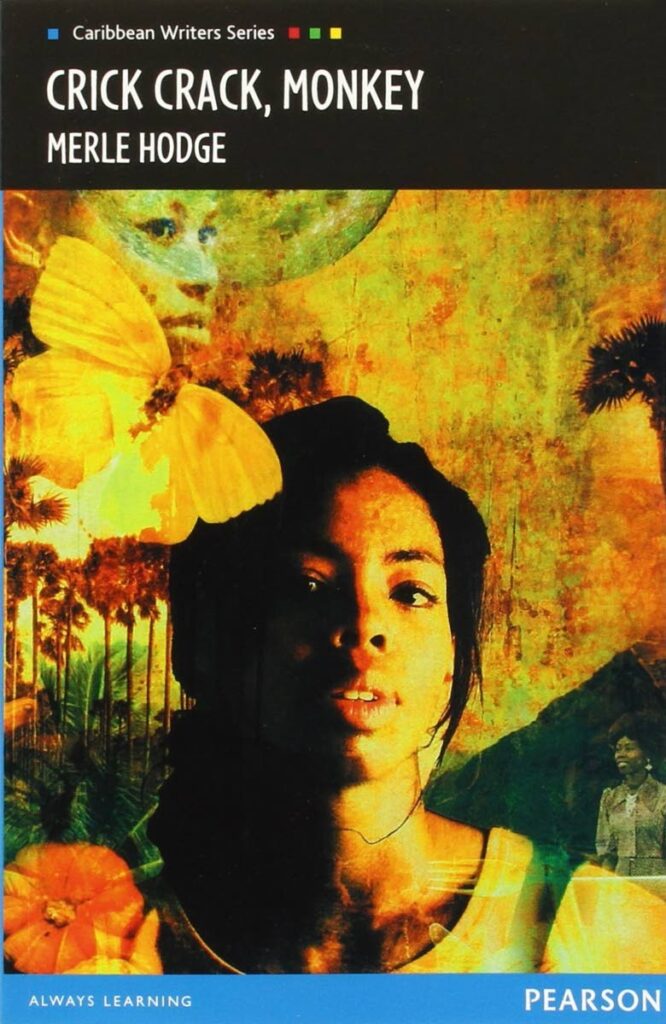

And in TT, a young woman grows up in Merle Hodge’s Crick Crack Monkey. Tee, the main character, is forced to navigate her way through colour prejudice, family complications and making sense of her identity. “...The darker you are, the harder you have to try. I am tired of telling you that what you don’t have in looks you have to make up for otherwise.”

The Caribbean tradition of books for children is wide-ranging and inspiring. Through expressive prose and captivating design, authors of children’s books explore very adult themes from discrimination to dictatorship and anti-colonialism. As we commemorate International Children’s Book Day today, I wondered, what role does reading play in the lives of children in our country? More importantly, as we face multiple crises within our families and communities, can the simple act of reading make a difference in how we face these challenges?

This week, thousands of children lifted their heads from overworked desks after completing an exam for which they had been preparing for years. Apart from the obvious relief, their thoughts would no doubt have turned to what their future could look like based on the results. Would they be condemned to the schools where education serves as a mere backdrop to social issues, or would they get into the school that will open doors and set them on a clearer path to success?

While reading books will not fix an education system already littered with divisions and conflict, if more students chose to read for pleasure it would certainly move us closer to the balance that we so urgently need.

In the 1940s, the mobile library was established, allowing citizens in remote areas of our country to have access to books. Today, it is more likely that children would have access to books on their tablet, phone or other device. While this is not necessarily good or bad, the question is: how do we manage this new way of accessing information to help heal our communities and encourage national pride?

The first stage is encouraging parents to read to their children. Experts recommend that this should begin as early as pregnancy and continue through the early stages of the child’s life. But can enough parents read or access books? And how accessible is literature for children from TT or the Caribbean? Would parents even know what to ask for?

In the 1980s, Merle Hodge, Eintou Springer and others from the 1970 Black Power Revolution in TT sought to address precisely these questions. They formed part of a team responsible for crafting the Grenadian curriculum in a culturally relevant way. Under the mandate of the Maurice Bishop government, Hodge designed and scripted Marryshow Readers, named for Albert Marryshow, a key Grenadian politician and one of the driving forces behind the West Indies Federation. The readers were designed to be an integral aspect of “an education system that marked the Caribbean child present.”

In 2022, increasing conversations about the damage left by the legacies of colonialism, indentureship and enslavement offer another opportunity to revisit the importance of culturally relevant education championed during recent Caribbean revolutions. However, calls for reparations and other rhetoric must be supported by actions that move us closer to the self-determination envisaged by George Lamming, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Claudia Jones, Sam Selvon, CLR James, Bob Marley and others.

A national reading project would not only make literature for children available to parents and educators, but would provide young people with the tools for creating their own books. On this day that celebrates literature for children, we must think about how we can inspire more children to write about their experiences towards the empowerment of us all.

Every day we face a number of challenges which not only threaten our nation, but the survival of our planet. Children’s books may not save us from global threats, but they can certainly help us work together to face the perils of this world. Just ask the revolutionaries among us; they already know how the next chapters in this new story should be written.

Dara E Healy is a performance artist and founder of the Indigenous Creative Arts Network – ICAN

Comments

"Building a nation with books for children"