The Putin output

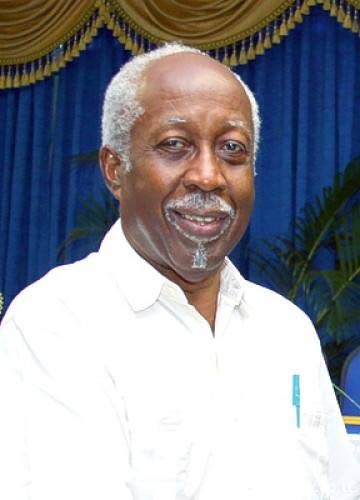

REGINALD DUMAS

Pt III

I’VE BEEN reading a March 2014 article by Dr Henry Kissinger on Ukraine, Russia and the West. He makes several points that still resonate today. “The test of policy is how it ends,” he asserts, “not how it begins,” and he proceeds to wag a warning finger at the three protagonists.

“Russia must accept that to try to force Ukraine into a satellite status, and thereby move Russia’s borders again, would doom Moscow to repeat its history of self-fulfilling cycles of reciprocal pressures with Europe and the United States…(It) would not be able to impose a military solution without isolating itself at a time when many of its borders are already precarious.” As for Vladimir Putin, he “should come to realise that, whatever his grievances, a policy of military impositions would produce another Cold War…(He) is a serious strategist – on the premises of Russian history. Understanding US history and psychology are (sic) not his strong suits.”

For its part, the West “must understand that, to Russia, Ukraine can never be just a foreign country…Ukraine has been part of Russia for centuries, and their histories were intertwined before then…(T)he demonisation of Putin is not a policy; it is an alibi for the absence of one…(But) understanding Russian history and psychology (has not) been a strong point of US policymakers.”

So neither side understands the other! No wonder we’re in such a mess.

Kissinger regards the Ukrainians as “the decisive element.” He states: “To treat Ukraine as part of an East-West confrontation would scuttle for decades any prospect to bring Russia and the West – especially Russia and Europe – into a co-operative international system.” But “Ukraine has been independent for only 23 years, (and), not surprisingly, its leaders have not learned the art of compromise, even less of historical perspective…A wise US policy toward Ukraine would seek a way for the two parts of the country to co-operate with each other. We should seek reconciliation, not the domination of a faction.”

He then puts forward four positions he thinks might satisfy all sides: (a) “Ukraine should have the right to choose freely its economic and political associations,” (b) it should not join NATO, (c) it should be “free to create any government compatible with the expressed will of the people.” There should be “reconciliation between the various parts of (the) country,” and it should pursue a non-aligned posture “comparable to that of Finland.” (d) “It is incompatible with the rules of the existing world order for Russia to annex Crimea.”

Kissinger is largely right, but even he falls into the usual US triumphalism. “Russia must accept” what America sees as obvious. But why “must” Russia “accept” anything? (It certainly isn’t accepting any advice from others these days.) And why, given Russian history and his own personality, would Putin shy away from another Cold War? If the “test of policy is how it ends,” policy has therefore to be carefully crafted and implemented towards a defined goal.

Has the West understood that? If so, why the recent visit by US officials to Caracas, which attracted immediate bipartisan criticism in Washington? How does the US have official discussions with Nicolas Maduro as president, a man it has sanctioned, while simultaneously recognising his sworn political enemy, Juan Guaido, as the “legitimate” leader of Venezuela? Whatever the subsequent State Department “explanations” of the visit, did it explore – with a Putin ally! – the possibility of oil supplies from Venezuela following a ban on Russian oil imports? How might such a policy end?

Citing famous Russian dissidents like Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and Joseph Brodsky, Kissinger rightly stresses the cruciality of the interlaced links between Russia and Ukraine. But western foreign policy has treated Ukraine as “just a foreign country” outside Russia, and encouraged it to hold the West’s hand. Many Russians don’t see things that way, however; definitely not the hyper-nationalist Putin.

Kissinger joins Russia in opposition to NATO membership for Ukraine. But he then swerves again into seeing the world through the lens of the western intellectual and Washington insider, ignoring the very lessons of Russia-Ukraine history he has just asked us to bear in mind. It would offend against world order, he says, if Russia annexed Crimea.

But Crimea too is an integral part of Russian history! Kissinger’s article was published on March 5, 2014. Two weeks later, on March 18, Russia formally annexed Crimea. Whose “world order?” When, as Kissinger himself observes, the West and Russia don’t really understand each other?

However, at the time of this writing Russia and Ukraine do seem to be inching towards an agreement which, in Kissinger’s felicitous phrase, could bring “not absolute satisfaction but balanced dissatisfaction.” And end hostilities.

We shall see.

Comments

"The Putin output"