Importance of geology to TT's water supply

SARA-JADE GOVIA

In a small island state with a strong, successful history of oil and gas exploration, it is quite difficult to imagine a geologist doing anything else besides looking for oil and gas. If they are not doing that, then the next thing for a geologist to spend her/his time on is finding sand, clay, gravel, or limestone pockets in our aggregate-rich geological formations of our mountain ranges.

However, at the confluence of these two sectors (petroleum and aggregate) lie the geologists, the hydrogeologists, to be specific, who explore our islands’ complex geology for water.

Perhaps the first hydrogeological mission – the science of finding water using geology – in the country was inadvertently consolidated in a petroleum geoscience assignment, where geologists would often find freshwater in the shallower depths of the rock formations they drilled into. As geology would have it, freshwater pockets were found beneath oil reservoirs as the deepest well in the country, according to the Water Resources Agency (WRA), in Cap-de-Ville at a depth of 764 metres (2,507 feet) in the Erin Sands Formation.

Naturally, the valuable product at that time was not those freshwater lenses, or aquifers as hydrogeologists call them, but the deeper rock with hydrocarbon reserves. Nevertheless, these expeditions amassed substantially beneficial data and information that led to the development of water wells scattered around these oil and gas fields, where the harnessed water was first used for petroleum exploration operations and later, for community water supply.

The first water well in Trinidad, according to WASA, was drilled in the Diego Martin Valley in the 1890s. These wells, developed in the gravels of the Diego Martin Valley, were treated at the River Estate Waterworks and supplied west Port of Spain. In Tobago, WRA recorded the first exploration water wells, also drilled in sub-surface gravels, between 1911 and 1912 in Lowlands and Cove Estate.

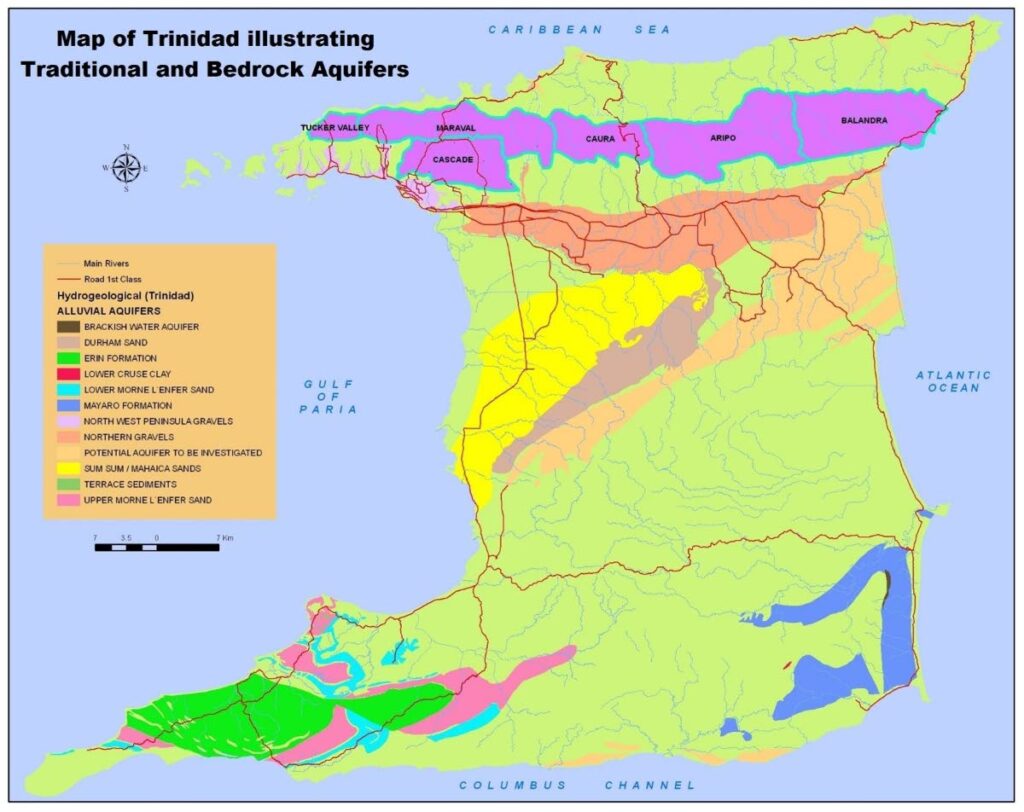

Decades later, TT has developed multiple aquifers spanning the Northern Range, Central Range, the southwestern peninsula and the southeastern coast from Mayaro to Guayaguayare.

In Tobago, the aquifer systems are spread across the Main Ridge. The Main Ridge has historically been a protected site for not only flora and fauna, but for the substantial role the rainforest plays in safeguarding the island’s water resources. According to Unesco, the Tobago Main Ridge is one of the oldest legally protected forest reserves in the world, proclaimed since 1776. Since that time, the Main Ridge was recognised as having significant value in attracting rain and storing water to maintain the rich biosphere.

The value of the Main Ridge for water resources is evident today in the location of Tobago’s more prolific groundwater wells which are found tapping into the fractures of the mountain range bedrock. Between 20 and 25 per cent of the country’s water supply comes from aquifers, with the remainder sourced from surface water systems (55-60 per cent from rivers, springs and reservoirs) and desalination (20 per cent).

The more prolific aquifers are found in the:

i) alluvials of the Northern Range foothills and are typically the sub-surface gravels, and

ii) sand formations, such as the Talparo Formation, of central and south Trinidad that are highly porous and situated between clay or silt lenses.

Map courtesy Water Resources Agency. -

A very prolific water well from Trinidad’s alluvial systems can produce near 500,000 gallons/day (approximately 12,000 bbl/day). According to the World Health Organization’s guidelines for water consumption of 44 gallons/day/person, a prolific well could supply a community of around 11,000 people.

The alluvial systems were found at shallow depths, with the shallowest well recorded in Trinidad, according to the WRA, in Santa Cruz at a depth of 9.75 metres (32 feet) in alluvium. There are also sand and gravel formations in Tobago that form aquifers, but the more prolific aquifer systems on the island are the bedrock aquifers.

In the early 2000s, WASA commissioned a project that explored and developed groundwater in the igneous and metamorphic bedrock of the Tobago Main Ridge. This was a landmark project for modern-day geology, undertaken by the consortium Earthwater Technology Inc on behalf of WASA, as it validated the occurrence of very deep-seated bedrock aquifers, termed megawatersheds. The deepest well in Tobago is found in diorite-gabbro of the Delaford Megawatershed in Louis D’Or, at a depth of 182 metres (597 feet).

Identifying the megawatersheds involved using geological, hydrological, geophysical, geomorphological and remote-sensing datasets to define the key structural features to delineate the favourable zones for groundwater.

A water well tapping these zones can yield closer to 700,000 gallons/day or higher. More than 90 per cent of Tobago’s groundwater comes from these bedrock aquifer systems, validating the sustainability of these megawatersheds as a secure source of supply.

Following the success of this Tobago megawatershed project, the exploration team moved on to help WASA source water from these systems in Trinidad. The more prolific system that was found in Trinidad is the Maraval Megawatershed, which traverses Moka, Paramin and Acono.

When water wells were drilled between 2000 and 2002, one of the wells produced near 1.9 million gallons of water per day (over 45,000 bbl/d). Unfortunately, the production of that well is now around 25 per cent of its original yield, potentially due to environmental changes, climate, borehole integrity or increased abstraction from the surface water systems; hinting at the possibility of interconnectivity between surface water and these deep aquifer systems.

The criticality of groundwater is evident during the dry-season months, as surface water systems become significantly depleted due to the deficit in rainfall. Groundwater wells therefore become an important supply source to augment production shortfalls from river intakes and reservoirs.

Particularly, groundwater development is a risk-mitigation strategy against water-supply threats, as wells can decentralise water-supply sources, reduce water transmission costs, are not immediately affected by rainfall shortages and have lower susceptibility to pollution events; but are certainly not resistant to contamination.

While groundwater is a risk mitigant, it is absolutely not risk-proof and is exposed to several perils that threaten the quality and quantity of the source. In TT, aquifers are threatened by contamination from agro-chemical waste and by-products, especially in the shallower systems, such as the Tacarigua Gravels.

Septic tanks and soakaway systems that are not properly designed, constructed and incorrectly situated also pose the hazard of contaminating aquifers from the seepage of untreated sewage. Perhaps one of the more substantial risks in the last few decades is saltwater intrusion into some of the country’s aquifers.

Saltwater intrusion is typically a result of either over-abstraction of freshwater from aquifers or sea-level rise. Both occurrences shift the fresh-sea water interface landward, resulting in changes to the saline concentration of the groundwater in the aquifers.

When this happens, the wells and even the entire aquifer system may have to be permanently abandoned. Milder cases can be left to be recharged via rainfall infiltration which after a few hydrological cycles may push the interface back.

To prevent saltwater intrusion, it is important to employ real-time monitoring of the piezometric surfaces – groundwater level in aquifers – and adapt a cyclic approach to water management where surface water is abstracted during times of higher availability, allowing aquifers time to recharge for harnessing during periods of reduced flow in the surface water systems (rivers and reservoirs).

Certainly, this is all dependent on the permeability and hydraulic conductivity of the aquifer, which would determine the recharge rate and feasibility of this approach to optimise groundwater resources while sustainably abstracting from these systems.

For World Water Day this year (2022) the UN is focusing on Groundwater: Making the Invisible Visible. This places emphasis on the role of groundwater in securing water at the utility scale, but also for businesses.

In TT, these are most predominantly bottled-water companies, beverage manufacturers, quarry operators and even agricultural operations. However, developing groundwater and securing these resources are strongly linked to robust land-use planning: ensuring that in groundwater recharge zones the permitted land-use activities do not contaminate the aquifers.

Additionally, land-use planning can also lessen the depletion of groundwater resources, for example, by considering availability and ability to source localised freshwater when approving construction, and avoiding competition between sectors that demand water, like irrigation and potable uses.

Undoubtedly, the value of monitoring water resources becomes central to sound management of groundwater and the urban planning nexus. Understanding the constantly shifting relationships in the hydrological cycle and its impact on the country’s groundwater reserves must have the same national attention as quantifying our hydrocarbon reserves. After all, our people and our bodies need water, from the sky and from the ground.

The Geological Society of TT is a professional and technical organisation for geologists, other scientists, managers and individuals engaged in the fields of hydrocarbon exploration, academia, vulcanology, seismology, earthquake engineering, environmental geology, geological engineering and the exploration and development of non-petroleum mineral resources. Find us on Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram and at thegstt.org

Comments

"Importance of geology to TT’s water supply"