In the still of the day

BitDepth#1342

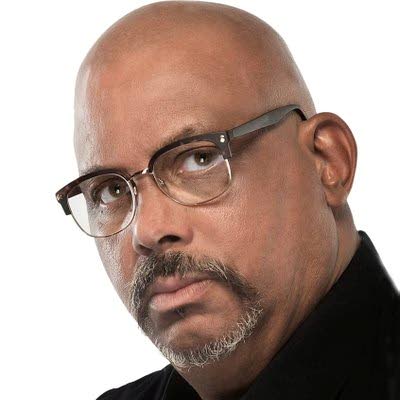

MARK LYNDERSAY

BY TWO in the afternoon, it was becoming clear that this was no typical power outage. Where I live in St James, exploding overhead transformers are part of the auditory landscape, regularly plunging sections of the community into temporary darkness, but normally coming back online within an hour.

This was different.

Just before 1 pm on February 16, the power went.

Within 20 minutes, Flow's internet service followed. A call to the company's helpline was met with a recording acknowledging a widespread loss of service.

Then TSTT's mobile data service went down, followed, within minutes, by its capacity to deliver voice calls.

By 4 pm, tap water was noticeably slowing.

This diary of my experience is singular to me, but it's clear that problems were widespread and prolonged.

Power was restored to the area around 11.45 pm. By then, TSTT's services were available, but Flow's internet was not.

For all the unforeseen inconveniences of that Wednesday afternoon that continued well into the night, it stood as a peaceful forewarning of the capacity failures in our most important utilities.

TTEC buys power from Independent Power Producers, the largest of which is Powergen, which produces 1,344MW, Trinidad Generation Unlimited (720MW) and Trinity Power (225MW).

TTEC has a 51 per cent shareholding in Powergen with a further ten per cent held by NEL Power Holdings, giving the State a 61 per cent controlling interest.

TGU is entirely owned by the Government and the only non-state entity generating local power is Trinity Power, formerly InnCogen and now owned by Carib Power Management, which has a contract to supply 195MW daily until 2028.

Two small TTEC-owned plants operate in Tobago – in Scarborough and Cove Estate.

In this context, the term "independent" is largely corporate fiction.

Overwhelmingly, the State buys the power it generates then distributes it.

Electricity pricing, true ownership and policy-setting power and the aggressiveness of the Regulated Industries Commission will be critical in analysing the reality of a public utility which, we discovered last week, can grind the operations of the country to a halt if it fails.

An island-wide blackout is a significant event.

Powering back up from zero distribution, a black start, isn't like flipping a light switch, it's more like controlling the pressure of water released from a dam.

The four UPS systems I use store just over 5Kva of power (https://bit.ly/3c792H1) and run computers and internet services for roughly two hours.

Telecommunications providers should be able to do better than that (Digicel did well and didn't hesitate to capitalise on that).

In a press release on the matter, TSTT stated, "While designed to last up to 4 hours, based on load, the back-up capability can be less. Given that the outage lasted over 4 hours, some of (the 610) locations went into outage and customers would have experienced challenges accessing voice and data services on the mobile network."

In my experience, it took less than 30 minutes for TSTT's services to completely collapse in my area and to remain so until power was returned.

While it is possible to store water in tanks and there is a choice of providers for telecommunications, there is no practical alternative for electricity currently being championed locally and no incentive to do so given its artificially low cost.

It's also surprising that WASA is so heavily dependent on direct electrical supply to provide basic pressure on its systems.

The State's heavy hand in managing and developing power generation and distribution and the disaster resilience of our major utilities must be subject to greater transparency and accountability.

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"In the still of the day"