Running a roti shop: Caterer Lalchan Basdeo withstands heat of rising costs

For over 30 years, cooking Indian dishes has been the source of livelihood for Lalchan Basdeo.

Basdeo, 52, known as the curry duck king, owns and operates Sham’s Roti Shop and Catering Services, a family-run business in Longdenville. He's a well-loved figure in his community, and is called Uncle Sham by most.

He wakes daily at about 4.30 am, says his prayers, and gets ready to go to the roti shop, packing his apron and cap to wear in the kitchen.

His menu has the favoured dishes of Trinis: dhalpuri and buss-up shut, or dhal and rice with a variety of vegetables and meat, including conch. Additionally, through his catering service he provides various Asian meals such as Chinese, authentic Indian and Thai dishes. He also cooks creole food and barbecue dishes on weekends.

When Business Day visited the roti shop on Monday to get an idea of its operations, Basdeo was busily seasoning meats to “chunkay” for customers. The aroma of geera, curry, garam masala and a special blend of spices and seasonings filled the air.

Preparation of the meats and vegetables is usually done the day before. Basdeo, his daughter Sheneil and about ten employees begin cooking from around 5.45 am in order to have all the dishes done by 10 am.

On a workstation, an employee was rolling out dough for paratha. She carefully rolled the dough to ensure that it was thin enough, so that it can be cooked evenly. The soft roti was then pounded to give it that “buss up shut (shirt)” look Trinis have come to love.

Basdeo said the pandemic lockdowns hit his business hard and they were trying to recover from a 40-45 per cent decrease in sales.

“I did not have to let go any of my staff and they understood and battled with me during the downturn. Even though we were opened for the Xmas period, the business was not doing well but taking care of my employees was critical. Their bonus was not much but they appreciated the little they got. My operations heavily depend on them.”

In the latest reopening phase, the Government announced that dining-in was an option once operated under the health regulations of a safe zone.

Basdeo said he has chosen not to allow dining so as to ensure his customers felt safe purchasing food from him.

“While this could reduce sales, it was something we collectively agreed to do because safety and peace of mind of our customers mattered.”

And he's also had to grapple with rising costs, the most recent being increases in flour prices – a staple ingredient of his rotis.

He uses the products of majority state-owned National Flour Mills (NFM), which at the start of the year increased its wholesale prices between 10 to 22 per cent. Privately-owned flour supplier Nutrimix also raised its prices.

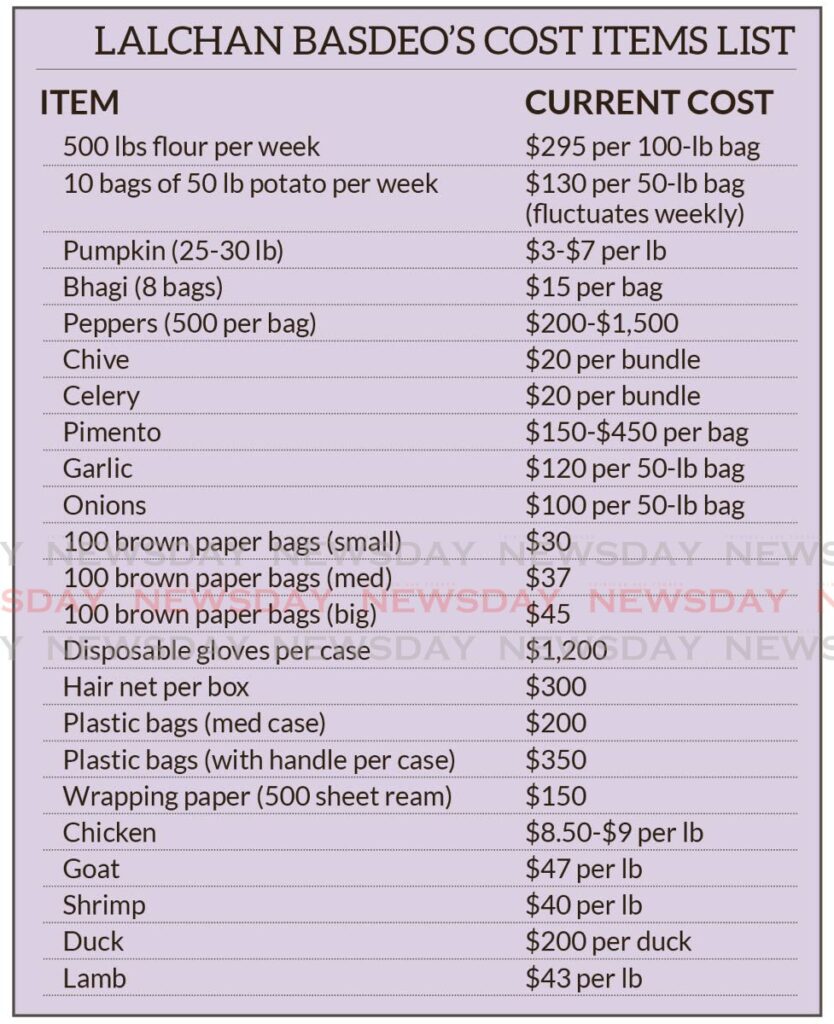

According to Basdeo, he now pays $295, up from $260, per 100 pounds, for the NFM flour he uses. He uses 500 pounds per week.

Likewise, vegetable prices have been fluctuating, which has made budgeting for steady output difficult. Meat prices, for mostly beef, goat and duck, are also costlier after local livestock producers raised prices too.

On a good day, 150 rotis plus 50 rice-based lunches can be sold, but on a bad day most of the food remains on Basdeo's hands.

Despite Government's efforts to ease the burden of higher food costs by removing value-added tax (VAT) on several food items in November last year, he said there has been no real change in his expenses for the business.

The VAT-free items used in his business include vegetable/soya bean oil, coconut oil, canola oil, butter, black pepper, and other spices, geera (crushed or ground), soya chunks, orange juice, apple juice, and still water (bottled water).

“The total on bills remained the same and, in some cases, it even went up, probably between two-five per cent. We are paying more for the dry goods but as much as we may want to raise the price on our food, we can’t.

“Early last year when meats prices went up, we raise prices, so to do that now would take a negative toll on the business. It is just too soon, and we are forced to absorb the increases. Every week the prices on the dry goods fluctuate.”

Basdeo said they also try to engage local farmers in the community as much as possible but shopping around has become a norm so that they can get the best deals based on the quantities they need weekly.

Asked whether changing product brands would be an option to maintain his business, Basdeo said, “definitely no.”

“We need to maintain a standard and that standard is our identity and brand which cannot be compromised. If we change the brand, there may be a lower quality of food and we are about quality and quantity.”

Basdeo said it was disheartening to see on social media people bashing small business owners, especially in the food industry about increased prices. Recently double vendors announced a $1 price increase to $6.

He said there were many other costs that affected food businesses.

Apart from price increases in food items, Basdeo said costs on other items such as napkins, paper bags, wrapping paper, forks, spoons, and boxes have also increased.

He said because he have opted to utilise a fully take-away service, the cost factor for these items have heavily impacted his operations.

“Everything single thing has raised, and people also need to take into consideration these things. For example, when broken down, a basic roti costs between $22-$23 to make, and then sale price is about $27. Out of that $27, rent needs to be taken out, and other cost for raw materials.

“It’s not everyday sales will be the same. There are good days and then there are the really bad days.”

Running a food business is a lot of labour, Basdeo said, but for him it remains a labour of love.

Comments

"Running a roti shop: Caterer Lalchan Basdeo withstands heat of rising costs"