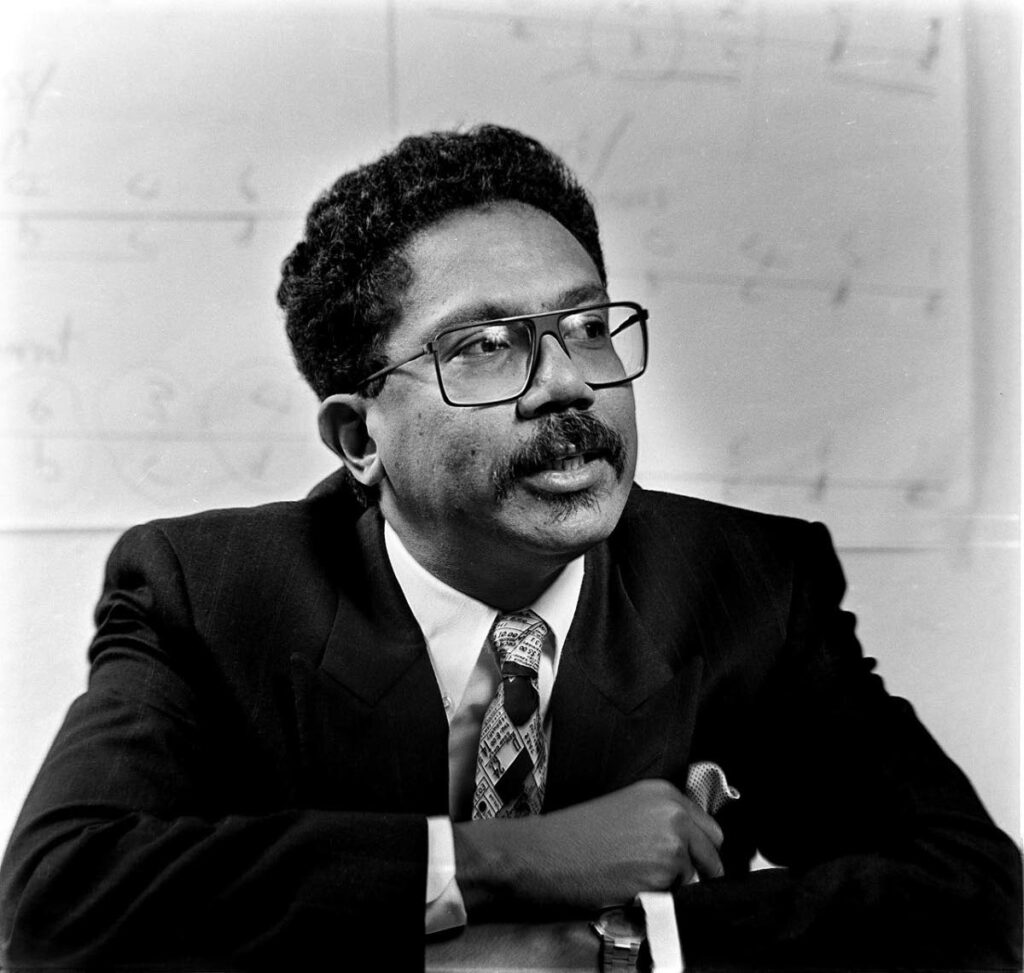

Alwin Chow, an accountant who became a media man

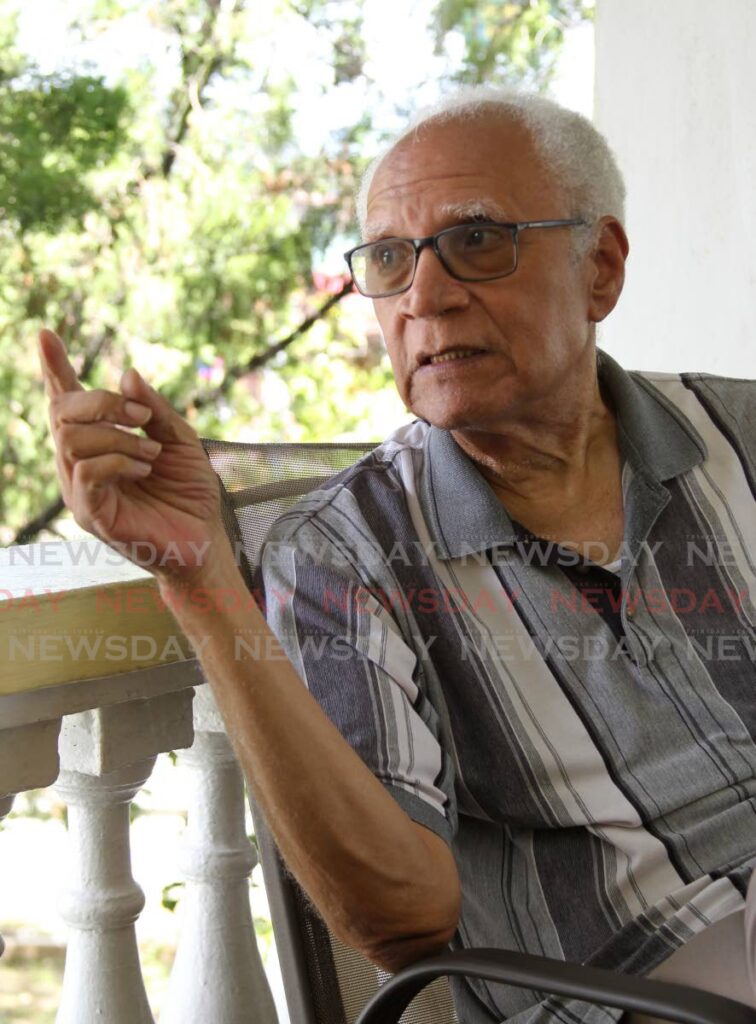

Alwin Chow was the person responsible for rejuvenating the idea of freedom of the press in TT, according to local media stalwart, Jones P Madeira.

“Alwin Chow would have loved to be regarded as the consummate media man, especially one in newspapers. This belied his very casual personality, an attribute which he could convert very quickly into the caustic, especially when he was being forced to be otherwise.”

Chow, 72, died in New York on December 9.

He was the husband of former Miss Universe Janelle Penny Commissiong-Chow, a chartered accountant, former managing director of the Trinidad Publishing Company, now Guardian Media Ltd, former chairman of the Trinidad Broadcasting Company, a former general manager with the Trinidad Express, and CEO of Trinity Housing Ltd.

In addition, he served as an opposition senator under the United Labour Front from September 24, 1976 to September 18, 1981, and as an independent senator from November 27, 1981 to October 29, 1986.

Madeira, editor-in-chief of Trinidad Guardian in the early 90s, said he and Chow oversaw the transformation of the operations of the paper. Chow wanted more exclusives, more investigative reporting, and to improve the product in general. He always wanted articles to be correct, celebrated whenever reporters had an exclusive, and ensured the paper was “on par with or better than” the rest.

“At the editorial level, Alwin did a lot of work with us whenever we gathered to do special coverage and so on. He attended meetings of the editorial department every morning. That, in a way, allowed some people to think there was interference. The fact is, he never interfered. He joined, suggested things like elements of a story we would not have gotten and would reveal all these things at the meeting.

“He was really an essential part of what we produced on a daily basis. If he had to be tough, he was, and if he had to give praise, he would do that as well.”

Madeira said Chow was never afraid to “take on” anyone. This was proven when, in 1996, the government under former prime minister Basdeo Panday was allegedly trying to get the newspaper to align its articles to their thinking. Chow, Madeira, Maxie Cuffie, and other senior journalists refused and resigned.

Madeira recalled a group of them believed they should “continue something” with the journalists who left so they started the weekly Independent paper. Chow, he said, took part in the arrangements and was appointed chairman of the board. And even when he had other responsibilities, he never abandoned the Independent.

He described Chow as a very bright person with his fingers on the pulse of the nation so as to better understand what was happening on both media and governmental levels.

Communications consultant Nicole Duke-Westfield recalled meeting Chow at a University of the West Indies job fair where he was engaging the students in conversation and inviting graduates to consider applying to the Guardian since they should be able to write and do research.

She believed he wanted people to be excited about being part of a news organisation. He also wanted to broaden the newsroom operation and if he was going to build a more professional media house, he felt he should start at the university level, she said.

Since Duke-Westfield studied language history and sociology, journalism was not something she had considered pursuing. But Chow was convincing, so she applied and in 1991, he hired her and several other UWI graduates.

She described him as shrewd, fair, and fearless, a man who gave 100 per cent and expected it of his employees. He was instrumental in setting her on the path of media.

“He was a very direct person. He was the kind of person that you either liked him or you didn’t. There was no middle ground. But he had a vision for how he wanted the newspaper to grow and develop, and part of that included bringing in technology.”

“He wasn’t a journalist, but he understood how important journalism was in the development of a nation. And that is something that is critical if you’re going to be involved in media. It’s not just about writing a story, putting out a product or selling an ad. He understood exactly what we were supposed to be about.”

She said at that time the 1990 attempted coup was still on people’s minds. There was an emotional connection and understanding of a change happening in the country, and the media was a big part of that change.

She believed that played into the thinking of Chow, the other executives and senior journalists at the Guardian.

Duke-Westfield said it was an exciting time for many of the young and senior journalists because Chow was determined to upgrade the newsroom.

There were a few Microtek computers and everyone had to share. He was instrumental in getting more and better computers, as well as introducing technology to the page-building process.

“What Alwin Chow was really instrumental in is helping to democratise the newsroom because more computers gave all of us the opportunity to work more effectively.”

Writer and photographer Mark Lyndersay worked with Chow from the end of 1989 to the beginning of 1992. He asked Lyndersay to do training and assessment of the Guardian’s photographic department and when he delivered the report, asked who he would recommend executing it. And so Lyndersay joined the Guardian as its first Picture Editor at the end of 1989.

"Alwin Chow was passionate, sometimes overbearingly so, about his ideas. He undertook to make the Guardian a true mass appeal paper and anyone who aligned with those goals was endorsed and supported, anyone who didn’t was in for a difficult time.

"He was direct, intelligent and willing to discuss what needed to be done, but once a decision was made, he left you to your own devices and expected results. In many ways, he was the perfect manager."

Detailing the technological advances mentioned by Duke-Westfield, he said at the time the Guardian’s text was input into Microtek word processing terminals. Subediting was done there, printed, and long strips of text were assembled by hand.

Chow was aware of desktop publishing, largely driven by Macintosh computers, and resolved to bring the technology to the paper. He brought in new equipment, assigning more capacity to support and pushed everything forward very quickly.

“Looking back, it was a kind of madness, supported by his unflagging determination and apparently, a capacity to get Ansa McAl to finance the dream.”

Some subeditors refused to use the Macs so Chow threatened to fire or reassign them, but instead, he created a system of paginators, who would build the paper to page plans laid out by the subeditors.

Reminiscing on the kind of man Chow was, Lyndersay said, "On the first day that printing resumed at the Guardian during the coup, he was there as the papers rolled off the press first thing in the morning, tossing bundled papers into waiting vans to be taken to distribution points. The image I have in my mind, which I didn’t have a camera to photograph was majestic in a military sense, his urgings and involvement spurring everyone on in the face of the disaster and tragedy all around us."

Sunday Newsday understands that up to Friday, Chow’s body was in New York and funeral arrangement had yet to be confirmed.

Comments

"Alwin Chow, an accountant who became a media man"