Architect, photographer Brian Lewis pleads case for Port of Spain

MARK LYNDERSAY

Brian Lewis's visual survey of Port of Spain gets off to a stumbling start with a foreword by mayor Joel Martinez that is startling in its cluelessness.

Martinez considers a city of "structures which symbolise power and force " alongside "quaint gingerbread homes," both of which "transform into a Carnival spectacle at the drop of a hat."

It’s probably unfair to pillory the mayor, who might have been saddled with a metaphor-prone speechwriter, but it's long been a city management strategy to laud its beauty spots while stepping gingerly over its effluvium.

While the book, Port of Spain: An Architectural Record, is long on words, offering up a diversity of opinions and perspectives on Port of Spain's history and potential, it is the photographs that sit front and centre as a document, narrating a history of development and aesthetic conflict.

The photography of the book is Lewis's usual considered, architecturally correct work, carefully timed for optimum light on the structures’ facades. Faced with subject matter that might be considered occasionally dreary, he declines dramatic angles and considers it with a relentless perspective: that of a viewer facing the building from across the street.

There are few angles on these structures, and those that exist emphasise some aspect of the subject building that isn't immediately clear from that direct, face-on contemplation.

Asked about these challenges, Lewis responded: "These images are records, not heroic architectural photographs.

throughout Port of Spain. -

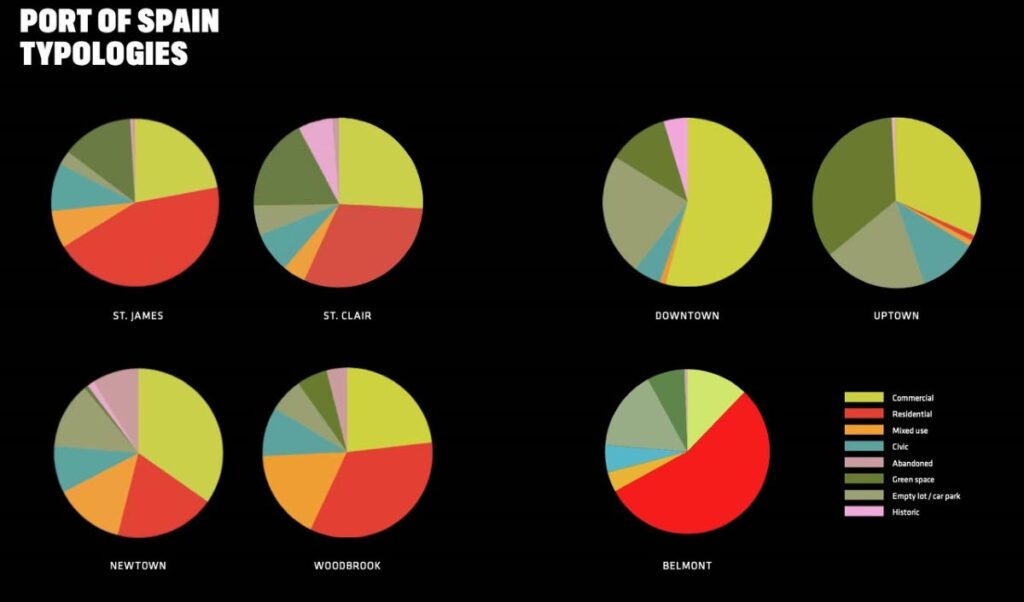

"Yes, hedges, walls, cars, wires were a constant challenge – some districts were more challenging than others – Belmont for cars, St Clair for walls.”

This assembly of buildings gathers the many architectural designs that make up Port of Spain, from those crafted through historical inspiration and religious aspiration to works that can only be described as the result of design whimsy. The brutalist and the ornate sit alongside each other cheerfully, every creed of architectural design finding an equal, if not always harmonious place.

Of the houses that are recognisable as Port of Spain buildings of ancestral provenance, some are dramatic commercial refurbishments that offer a nod to their original design concept; others are in marginally contained disrepair, their history showing in rotting wood and rusting galvanise.

One quaint and well-maintained gingerbread building is bracketed between a faux modernist blue wall and the insistent echo of modernist architecture as social aspiration as a tower of One Woodbrook Place looms like a photobomber behind it.

In another image, an ageing wooden house sits on flaking noggin, visibly bowing inward to the weathered steps that rise to the entranceway at its midpoint. In that open doorway are a disembodied pair of legs, their owner having pulled a bashful curtain in front of herself.

And all that's in St James alone.

While the photographer has an active voice in the text segments of the book, he sensibly draws on a range of concerned citizens who bring their own perspectives to the development – past, present and future – of the capital city. Geoffrey MacLean traces the history of the development of the Amerindian fishing village of Cumucurapo, the ornate and lavish structures that drove its development into a major port and sprawl to the north and west as more and more land was given over to business.

In the wake of Lewis's blunt survey of selected buildings, several essays consider how to move forward through redesign, adaptation and rethinking architecture as a more central aspect of cultural orientation.

Margaret McDowall of the National Trust explains how conservation of the country's built heritage can be achieved, but emphasises that the best option for preservation is use, whether as a historical artefact or in an adaptive reuse of the structure, which uses the building either residentially or commercially while preserving its character.

This doesn't happen very often. It's much easier to tear down a building than to sensitively repair and conserve it.

The essay series closes out with a consideration of the business of the city centre, which inevitably becomes a contemplation of the politics of the city's governance structure, by Gregory Aboud. His impassioned plea for accountability and transparency in the city's administration and greater attention to the actual results of the annual allocation given to the city corporation are both sensible and likely to be ignored. Changing that would fundamentally change the balance of power in Port of Spain proper from being driven by the largesse or frugality of the State to one which would give greater weight to commerce and investment in a city from which businesses are fleeing.

Lewis's book will be launched on December 8 at Medulla Art Gallery, Woodbrook, for limited in-person guests.

An exhibition of selected works will be on display and books will be available at the gallery until December 15

Comments

"Architect, photographer Brian Lewis pleads case for Port of Spain"