The citizen and the Constitution

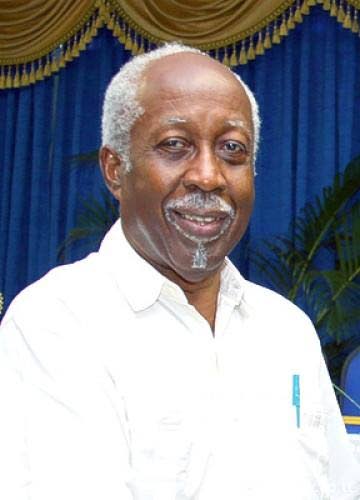

REGINALD DUMAS

Pt I

I HAVE declined a multitude of requests to comment publicly on the Police Service Commission (PSC)/Police Commissioner/President/Government/Opposition kangkatang, though, like many, I am dismayed by the sustained assault to which good governance is being subjected. And there’s something you may not know. Although the temperature and decibel levels are much higher today, and the societal implications more serious, there was a similar occurrence nearly 30 years ago, involving a president, a prime minister, PSC chairman, and a commissioner of police. The chairman concerned, the late Kenneth Lalla, wrote about it in his autobiography I Am a Dream To My Village. And Lalla didn’t tell all.

My own experience with a president, a government and a PSC might also be of interest. Section 122(3) of the Constitution states that the President, after consultation with the Prime Minister and the Opposition Leader, is to nominate for membership of the PSC people “who are qualified and experienced in the disciplines of law, finance, sociology or management…” Section 122(4) says that notifications in respect of the nominees “shall be subject to affirmative resolution of the House of Representatives.” After such resolution, the President makes the appointments under section 122(5).

In September 2013, I concluded, after examination, that one of the then President’s nominees for the PSC only partially satisfied the criteria for membership, while a second didn’t satisfy any at all. I decided to query this, and, on my behalf, the late Karl Hudson-Phillips wrote the Attorney-General (AG), with a copy to the President, saying that, should the nominations be approved by the House of Representatives, I would “take such steps as (I might) be advised to ensure compliance with section 122(3) …”

As I anticipated, I was ignored. The House approved the nominations; appointments followed. I thereupon instructed Hudson-Phillips to commence action against the AG, seeking a High Court interpretation of section 122(3) in relation to the two appointments. I made it clear to the court that my interest wasn’t personal. “Rather,” I said, “I was and am concerned as a citizen who has for many years written and spoken publicly about the need for good governance in this society, particularly including respect for our institutions such as the Constitution, which is the highest law of the land. I am therefore acting in what I consider to be the public interest of Trinidad and Tobago…It is in the public interest that the PSC be properly constituted under the Constitution.”

The following year, 2014, the High Court dismissed my application on procedural grounds. Section 14(1) of the Constitution permits a person to apply to the court for redress if any contravention of the provisions of Chapter 1 of the Constitution occurs in relation to that person. I, however, had approached the court as a concerned citizen, not as a directly affected individual, and I was therefore deemed to have no standing before the court. I considered that position anti-democratic, a constitutional deficiency, and I appealed.

Later that year, the Court of Appeal ruled unanimously in my favour. I quote from its judgment: “In our opinion, barring any specific legislative prohibition, the court, in the exercise of its supervisory jurisdiction and as guardian of the Constitution, is entitled to entertain public interest litigation for constitutional review of non-Bill of Rights unlawful constitutional action, provided the litigation is bona fide, arguable with sufficient merit to have a real and not fanciful prospect of success, grounded in a legitimate and concrete public interest, capable of being reasonably and effectively disposed of, and provided further that such actions are not frivolous, vexatious or otherwise an abuse of the court’s process.

“The approach to be taken to this issue of standing is a flexible and generous approach, bearing in mind all of the circumstances of the case…The public importance of the issues raised and of vindicating the rule of law are (sic) significant considerations …

“Standing is a matter of discretion…Ultimately…context is the determining factor…For example, where the alleged unlawfulness affects the public generally, no particular or direct interest in the matter may be necessary…In this case, Mr Dumas contends that the nomination and appointment of two individuals to the Police Service Commission by the President were unconstitutional…In our judgment, this represents a legitimate interest in having a properly constituted Police Service Commission…This is a sufficient interest in the context of this case…to vest the applicant, prima facie, with appropriate standing to bring and continue this action.”

The High Court judge who had found against me was declared to have “erred in his analysis of the issue of standing and jurisdiction…”

Comments

"The citizen and the Constitution"