Afghan callaloo

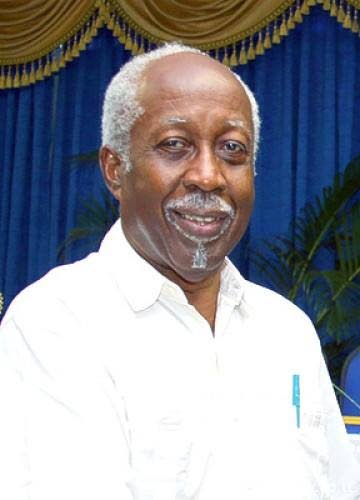

REGINALD DUMAS

Pt III

THIS ARTICLE will look at some of the international ingredients of the Afghan callaloo.

There is China, I expect gleeful at recent US discomfiture. But when your goal is to be the world’s No 1 power, glee is by no means as important as dispassionate planning, and the Chinese are good at that. You want to be on friendly terms with as many as possible, especially your neighbours, and China has excellent reason to be cautious around the Taliban.

Look at a map of the area. Landlocked Afghanistan is essentially bordered in the west by Iran, in the east and south by Pakistan, in the north by Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. All are Muslim states. (In its remote northeast it also has a short border with China.)

North of Tajikistan is Kyrgyzstan, another Muslim state, which borders the Chinese province of Xinjiang, heavily Muslim, where China, in line with its policy of central control and “Sinification,” has been doing its best (many say its worst) to “educate” (or “re-educate,” I’m not sure which) the province’s Uighurs, themselves Muslim and allegedly separatist.

Beijing doesn’t want any more religious, hence political, problems in Xinjiang, which would certainly happen if the Taliban start trying to propagate abroad their tunnel-visioned interpretation of Islam.

Russia is another protagonist. Like the Chinese, the Russians would have been ecstatic at US embarrassment, but for a different reason. Russia is still smarting from the forced departure of the Soviets from Afghanistan in 1989, largely as a result of the unrelenting guerilla war waged against them by US-financed mujahideen.

Vladimir Putin, who learned from that experience, recently called for an end to the “irresponsible” efforts of the US to enforce “its own values on others and attempts to build democracy in other countries” without taking those countries’ cultures and traditions into account. Russia has no common border with Afghanistan, but it too is seeking good relations with the Taliban – a finger in America’s eye.

Pakistan has always struck me as an unsteady nation, caught between politics and God. It’s like a nominal garden of theocracy with unruly sprouts of constantly competing international interests and of secularism. Decision-making cannot be straightforward. I have no doubt, however, that, because of its close traditional links with Afghanistan, it will continue to play a leading role. (For instance, its prime minister, Imran Khan, is a Pashtun, and the Pashtuns are Afghanistan’s largest ethnic group.)

And though Iran’s mullahs already have much to occupy them, they will be paying close attention to the fate of the Afghan Hazaras, their fellow Shia sectarians.

What to say about the US? In my next article I’ll examine President Biden’s “post-withdrawal” address. For now, just a few general remarks.

The “super-power” status conferred decades ago on the US has ironically been one of the country’s most damaging handicaps. At the end of World War II the US was pre-eminent: it was, everywhere, unquestionably “primus,” first; there were no “pares,” no equals. It has been a generous country: the Marshall Plan lifted a battered western Europe from the floor of indigence; the Peace Corps came later. But, perhaps unsurprisingly, that generosity was accompanied by a conviction of moral superiority. Cultural particularities were ignored; the “American way of life” was the one to emulate. And, alas, too often to be imposed.

The great deity was “democracy.” (But democracy is more readily accepted abroad when it’s seen to be consistently and even-handedly practised at home.)

The great Satan was communism, and everything deemed, however faintly, to resemble it. American “interventions,” generally ideological, in others’ affairs would follow. An unfortunate contradiction emerged: too many saw only “the ugly American,” while for triumphalists like former US secretary of state Madeleine Albright, America was “the indispensable nation.”

The western hemisphere was American, of course; the Monroe Doctrine said so, didn’t it? An embargo of Cuba, more hurtful to the people than to the leaders at whom it is theoretically aimed, persists. After 60 non-productive years, it is widely perceived as spiteful, not as a manifestation of moral superiority.

Biden has now announced a focus on national security, but policy is a multi-dimensional affair. If I were he, I would establish a commission to examine overall US foreign policy and make recommendations. Ours is a more complex world than those of Ronald Reagan or George Bush, or even Barack Obama. (Donald Trump’s world escapes my understanding.)

We confront rapid climate change and degenerating environments, massive migrations, assertive minorities, clamour for gender justice, health crises, obscenely widening income and social inequalities, persisting racial tensions and religious extremism, mind-boggling technological developments, externally-influenced domestic terrorism, etc.

The US needs an overall recalibration of its foreign stances.

Comments

"Afghan callaloo"