My great-grandfather’s legacy

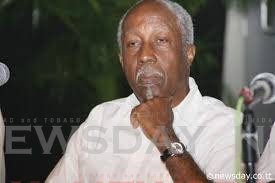

REGINALD DUMAS

Conclusion of article on Reginald Dumas’s great-grandfather, Norman McNeil. According to the February 1822 Annual Return of Plantation Slaves, he was born on the Dunvegan Estate, in the Whim district of Tobago, on July 3, 1821. Today is his 200th birth anniversary. The first part was published on Friday.

THE HISTORY of relations between the Christian church in general and the institution of slavery is an inglorious one. While there were missionaries and priests and clergymen who saw, and were appalled by, the obvious conflict between the tenets of their religion and the realities of slavery, the economics of the sugar plantation prevailed.

Well might the biblical book of Galatians urge that we should “stand fast…in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free, and be not entangled again with the yoke of bondage,” and proclaim that “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free.” But such concepts were, understandably, anathema to the planter class; no self-respecting slaveowner could possibly accept them. It is a little-known fact that a so-called “slave Bible” was therefore written, specifically for use by the enslaved, which deliberately omitted passages like those, deemed subversive.

The reality was that profit trumped pulpit. An accommodation was reached between priest and planter, made easier by their common conviction that the slave was not in any case entirely human: both agreed that emphasis would be placed on obedience. The late Elsa Goveia, Professor of History at the University of the West Indies, described the arrangement this way:

“To secure toleration for their efforts to propagate the Christian religion among the slaves, the missionaries accepted the system of enslavement and the necessity for subordination which it created…(O)ne of the chief tasks of all the Christian missions (was) to inculcate among their Negro converts the duty of submitting to authority, particularly the duty of obeying their masters…”

It was cynical, if effective, symmetry. The theme of obedience was common to both areas of activity: obedience to the plantation lord, obedience to the Christian Lord. In starting his day and Sunday schools in 1829, the owner of the Whim estate, John Hamilton, brilliantly merged both concepts: he kept slaves, but he was also, bewilderingly, an Anglican reverend. A planter-cleric, he obviously saw no contradiction in simultaneously and contentedly serving God and Mammon.

Mind you, Hamilton was careful not to let his young slaves get ideas of freedom and equality, and forget who they really were: the day school operated only three times a week – emphasis, naturally, was on scriptural studies – and only from six to eight in the morning. Thereafter, it was back to the fields. Only in 2006 did the Church of England formally apologise for its unheroic role in slavery and the slave trade. 168 years after emancipation! These things take time, I suppose.

Emancipation or not, however, the psychology of the plantation continued to hold sway, and that psychology infused the Christian church. My great-grandfather, Norman McNeil, was labouring in his Whim school (which also held Bible classes); he was labouring for Anglicanism. Without formal training in either academic or ecclesiastical matters, he unsurprisingly made many mistakes. But in 1849, instead of extending sympathy to him, and offering to assist, the Rev Herbert Melville, a British import and curate of the Scarborough church of St Andrew and St George, flagellated him and Thomas Dove of the Hope Estate School.

Susan Craig-James quotes Melville as deploring the “weak and palsied instruction” at the two schools, and teachers “notoriously inefficient from want of knowledge…which they offer to impart, while even the little they may possess is impotent and useless…” Attendance at the schools was poor “because the master does not educate.” But McNeil persevered. In 1872 his school placed ninth of 24 on the order of merit list, and was one of the top five with the most passes in the higher subjects (English history, geography, Bible history, etc).

The indifference of the colonial hierarchy – Melville’s dismissiveness was not unique – could not budge McNeil from his vision. Susan Craig-James writes that for several years, he was paid no salary at all, and it was only after he petitioned the Tobago Assembly that he received compensation – for one year only.

It wasn’t only the absence of a salary. Astonishingly, it was also the fact that for his first several years as headmaster (and, generally, the only teacher) he had no schoolhouse: he used his home, and sometimes, outside the sugarcane crop season, the boiling house on the Dunvegan Estate. His second wife, Rosetta, was for a short period the sewing mistress.

But McNeil would not be deflected from his goal – education, both secular and religious – whatever the obstacles in his path. In the Anglican Church itself, he became a lay preacher, a catechist and superintendent of the adult Sunday School in Scarborough. He would be taken aback to learn what “Sunday school” has come to mean these days in Buccoo.

Such was the public admiration for his unflinching and selfless dedication to church and school in the face of unending hindrances that he was one of the teachers who were popularly titled “venerable.” And a decade after his death, Mitchell Prince would laud him, and others like him in Tobago, as “black gentlemen who commanded respect from all classes alike, from governor to labour (sic). In social progress and material strength they have not many successors in Tobago.”

A gubernatorial nod of approval would automatically, in that very colonial period, have considerably elevated the societal acceptability of the recipient, but what to me is of much more importance was the evident approbation of the masses.

Many of McNeil’s descendants, in different parts of the world, will be commemorating his birth bicentenary today. The covid19 pandemic makes the entire event a virtual affair, but we will pay tribute to, and be inspired by, the legacy Norman McNeil left – of vision, of hard work, of determination, of commitment to religious principles and social and economic advancement, of dedication to duty. Born enslaved, he never saw himself as a slave, and his descendants should seek constantly to achieve his standards and goals.

And we would like to think that he would have approved the programme for education in the current United Nations International Decade for People of African Descent, and thrown himself enthusiastically into its implementation.

Comments

"My great-grandfather’s legacy"