Beneath the surface of things

Last week was the worst of weeks and the best of weeks. The messy vaccine rollout necessitated my bundling my 99-year-old mother into the car and striking out in search of a designated health centre in the hope of finding one without waiting lines and prepared to register us.

At Diego Martin, my good luck was in top gear. Having no wheelchair, I hoped to find a parking spot pretty close to the entrance. Miraculously, as if waiting for us, was a spot exactly in front of the gateway to an amazingly new and shiny building that houses the medical services for the area.

A wheelchair appeared, like magic, and in an instant we were being handed forms to fill in, since we had accepted the offer of being vaccinated without any need to register and return on an appointed date. Within minutes, our blood pressure was taken and we were ushered into another very well-appointed room for the inoculation.

It was an impressive operation and very reassuring, after all the uncertainty. It was also a very interesting experience, for it reinforced everything I suspect to be true about our society and its underlying faultlines.

A small exercise of power by the nurse who administered the vaccine suddenly piqued my interest. She was a complete kill-joy – obviously a long-standing professional who had seen everything before and believed that patients should accept pain and suffering.

She made me recall the spartan management of pain in the British National Health Service, ie as weak and as little pain relief medication as possible, and I guessed she had been trained there and was uncured of her reluctance to save people from their misery, especially someone like me, who was just too chirpy for her own good.

Half-jokingly, I had asked how long would it be before I could have a mildly alcoholic drink, since I was due to go to a small birthday dinner in a few hours.

“Forty-eight hours,” was her response. Furthermore, she advised that I should go home and rest quietly for the rest of the weekend.

Out of the sheer relief of having unexpectedly found the beginning of the end to my worries about keeping my mother safe, I was in a bit of a playful mood. I complained, tongue-in-cheek, that it would take more than the vaccine to keep me home that evening, after a year of being locked up pretty much continuously.

In her matronly way, she stuck to her guns, “You’d better!”

I could not reveal that I felt utterly crestfallen that my good luck should bring such bad luck in train.

Hoping for better news, I asked the cheerful young female medic, who undertook the post-vaccination monitoring, about the drinking time lag. She brought it down to eight hours.

Things were definitely moving in the right direction, except that my mother’s blood pressure was going through the roof. I calculated that if her blood pressure could regularise and I could still go out, it would be 10 pm before I could enjoy a celebratory glass of bubbles. Not that great, really, since 10 pm would be going-home time.

So I tried my luck again, being always inclined to rise to a challenge – my mother calls it living in hope – and put the critical question to the middle-aged doctor who finally gave us permission to leave.

It was a long shot that I would get the response I wanted, but to my utter surprise, he laughed at the notion that I could not have a glass of wine and get on with my life as normal from that very moment.

The reader can deduce a personal meaning from these events as they happened. I contemplated the throng of people who had suddenly descended on the place. It was a meeting of the affluent of the northwest with a Harts Carnival band.

I recalled the voiced fear and reluctance of poorer, unwell people to get vaccinated. Their failure to register was making it possible for walk-ins like my mother and I, who have no NCDs and were never intended to be at the top of the line, to get the valuable vaccination. It was a complex scene with social undercurrents.

Why was the nurse trying to frustrate me? Was she right, in fact? Were the doctors, with their differing advice, just exercising different levels of power over me, or keener still to show their own over other medical staff?

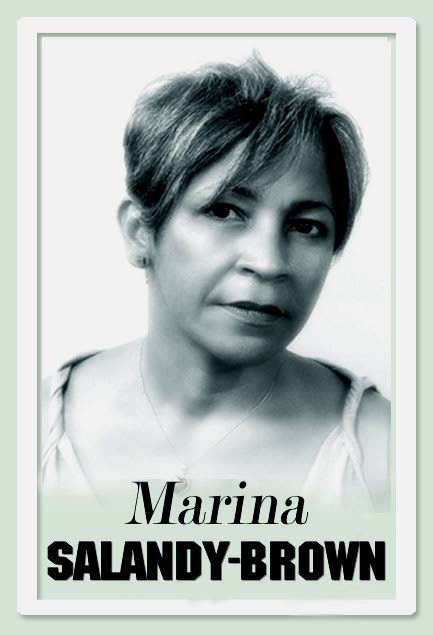

There is always something more in the pot than the spoon, or as we would say, more in the mortar than the pestle, and individuals bring their own perspectives to an event. This is where literature comes in. Fiction and poetry allow us to enter those separate realities and acquire greater insights into people and situations. In the NGC Bocas Lit Fest (April 23-25), there are a host of wonderful new books that take us beneath the surface of things. www.bocaslitfest.com

Comments

"Beneath the surface of things"