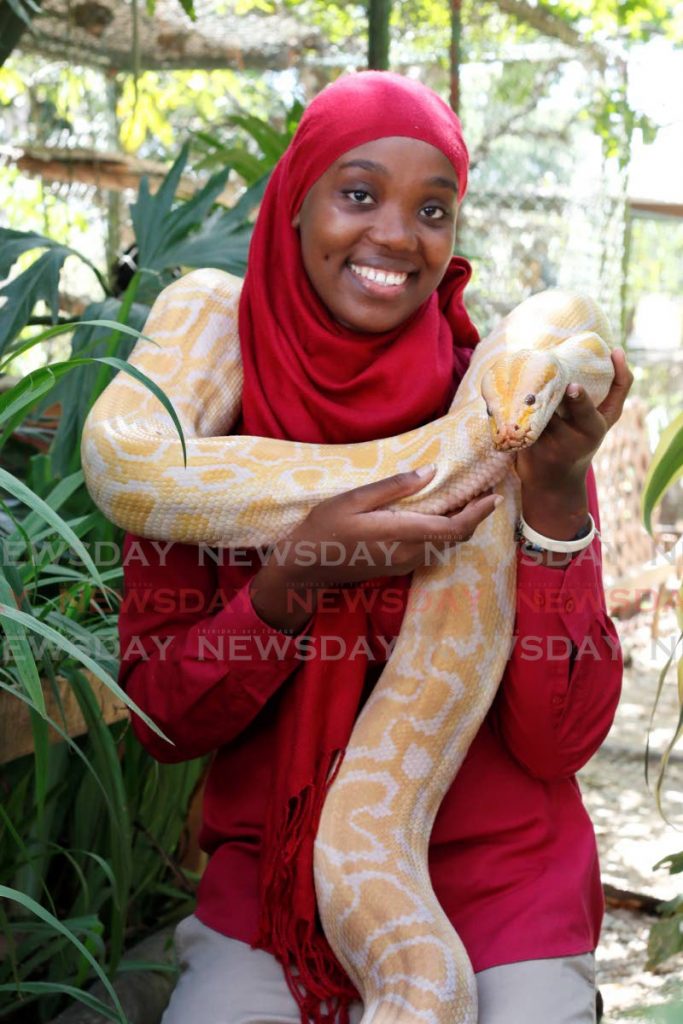

Hukaymah’s haven for rescued animals

Visitors to Hukaymah Ali’s home in St James may notice a few peculiar house guests: two raccoons, three tropical screech owls, a greyline hawk, an orange-winged parrot and a cascabel snake.

Asking what these animals are doing in Ali's home seems a fair question. Actually their stay is only temporary; her home is their haven after being rescued from distressing situations.

Ali is a senior volunteer at the El Socorro Wildlife Centre for Conservation in Freeport, often rescuing animals and caring for them until they can be released into the wild. She began volunteering in 2017 at El Socorro, where she did everything: she cleaned the grounds and fed the animals. Over time, she learned new skills.

She told WMN, “People would call (the centre) and report animals to be rescued. I would go out and rescue (them). Then I started rehabilitating the animals. There were a lot of animals to deal with.”

With the centre pressed for space, Ali began taking home the animals she could manage. She still does so today.

Caring for them, though, is no easy task; some are diurnal (day) and some are nocturnal (night) animals.

“I sometimes get up at 6 am to feed and take care of the animals that are active in the day. I also have to take care of the ones that are active in the night.”

It’s also costly for Ali, who is a full-time volunteer. Medication is expensive and animals are taken to the vet, as needed, to assist with their rehabilitation.

Ali can still access the El Socorro Wildlife Centre’s resources but limits her use. Why? She started caring for the animals at home to reduce the burden on the centre. This is important now more than ever. Owing to covid19, the centre is cash-strapped, with fewer visitors and donations.

In extreme circumstances, Ali may ask her 8,000-plus followers on Instagram to chip in a dollar or two. Then there’s her mother, who supports her work but isn’t fond of snakes being kept in the house.

When snakes escape their enclosure – which they often do – Ali has to do damage control with her mother. (Once, a snake escaped its enclosing and almost slithered its way into the washing machine.)

While it is challenging work, with no financial incentives, passion keeps Ali going. She always wanted to work with wild animals. As a young girl, she admired Australian conservationist “Crocodile Hunter” Steve Irwin.

“I was volunteering at a vet first and I found that it wasn’t enough…I was only seeing cats and dogs. I was searching for another place (where I could deal with different types of animals) and someone sent me to link to the El Socorro Wildlife Centre.”

She contacted the centre’s founder, Ricardo Meade, and started volunteering.

At the time, she had just started a degree in biology at the University of the Southern Caribbean (USC). As a child she liked veterinary sciences but thought vets only dealt with cats and dogs, unaware that the field had different specialisations. It wasn't so much that she minded caring for cats and dogs, but she wanted to work with other animals. So she lost interest and studied biology.

Volunteering at El Socorro opened her eyes to other possibilities and when she finished her degree she started studying basic veterinary sciences at the UWI School of Veterinary Medicine. She began earlier this year and when she's completed the basic degree, she hopes to specialise in wildlife veterinary.

“At the centre we still have to go by vets to see about the animals. So I thought that if I can rehab the animals already, why not be a vet?”

What happens to rescued animals after Ali cares for them at home?

There is no standard time frame for animals to recover; each does so at its own pace. Injured animals that make a full recovery are released back into the wild. Though rare, animals that can't be released are transferred to the centre, where they become educational ambassadors.

Ali doesn’t keep any as pets. In fact, she has no pets; she prefers to see animals living in the wild.

While she's cared for many animals, snakes are her favourite. And yes, she has been bitten, although the first time was orchestrated, just to see how it felt. Of course, she cautions other people not to try this – and certainly not with a venomous snake.

Ali isn’t afraid of any animal. She's allergic to some insects, but, she told WMN, "I will still hold everything.

“I get bitten from snakes all the time, get clawed from hawks and hold venomous snakes. I do everything.”

It’s no surprise Ali is heartbroken over the threats facing wildlife in TT. While some may think it’s laughable, local superstitions gravely affect how people perceive local wildlife.

“There are a lot of myths in regard to animals in TT. For example, someone’s grandmother will say a certain owl is a 'jumbie owl.If you see that owl, death coming.' People would kill an owl because of that. Here we have to tell people that those things are not correct.”

She also hates the “kill all” approach to snakes; it leaves local species vulnerable to population loss.

This is where education and awareness come in as a tool to help protect TT’s wildlife.

In addition to the El Socorro Wildlife Centre’s educational outreach activities across the country, Ali, and a group of volunteers at the centre also started the West Indian Herping Group in 2018.

Often done for research purposes, herping refers to the act of looking for snakes and amphibians in their natural habitat.

“We specialise in reptiles and amphibians (studies). We specifically educate the public on how to identify snakes, so people won’t just be killing all the snakes. We allow people to message us any time. If they see a snake, we encourage them to take a picture so we can ID it for them and tell them whether it is venomous or not.”

In addition to raising awareness, the group does research expeditions throughout TT. Its main focus is snakes but it also researches other animals. The data it has collected so far has provided valuable information for several local wildlife research papers. During a 2018 research expedition, members of the group stumbled upon a stygian owl, in the first sighting of the species in TT.

If people know enough local wildlife, Ali thinks they will be less fearful and understand their value.

“Once you educate yourself about an animal and learn everything about it first, then you can understand the animal. It is still your choice if you want to stay away from it, that’s fine. I don’t force people to be with animals – just don’t kill them.”

And she issues a gentle reminder: animals, especially snakes, won’t attack people unless they are provoked.

Ali wants current hunting legislation to be better used to help protect wildlife. However, she has little hope this will happen because of culture and weak enforcement of hunting laws.

“You can kill 100 manicous and nothing happens. You can kill endangered species like the leatherback sea turtle and ocelot…nothing happens.

“People eat every single thing that is moving. They eat monkeys, ocelots, and raccoons. It’s ridiculous. People are over hunting and killing out every single thing. So, what’s going to be left?”

TT's official hunting season, according to the Conservation of Wildlife Act, Chapter 67:01, runs from the first day of October to the last day of February. This year, however, hunting has been banned until further notice due to covid19 restrictions.

However, Ali is calling for a complete ban on hunting until the population numbers of hunted species, in TT, are properly assessed. Afterwards, she said, hunting should not be permitted annually but rather every three years. Hunted species should be able to replenish population numbers within this timeframe. Stricter hunting quotes and penalties will also help prevent overhunting.

Ali challenged more women and girls to get involved in wildlife conservation.

“I try to invite women to get involved, but they are just not as passionate. The main thing with this line of work is passion. If you are not passionate…you would not like it.

Ali said some women, for example, dislike insects. But that's just one aspect of wildlife conservation. She urged women to reach out to her, or the El Socorro Wildlife Centre, and try something.

Outside her wildlife work, Ali admits she has no other hobbies.

“My whole life revolves around wildlife. If I’m not volunteering or rehabbing, I’ll be out in the bush camping. When I have a stressful week, I go out into the bush and camp to relax.”

Safety is a priority. Ali never camps alone and always does so with members of the West Indian Herping Group. Camping locations are carefully scouted with the assistance of people who are familiar with potential camping areas.

And don’t think life has slowed down for Ali because of covid19. The work continues 24/7, with no days off.

“You always have to be vigilant that the animals (you are caring for) are okay. It’s always something.

"Even if I release the animals, and I have no patients, for one day I might get to sleep. But then I’ll just get a whole set the next day.”

In the future, Ali plans to travel to different countries to do wildlife rehabilitation and veterinary work, and hopes to discover new species both locally and internationally.

If you're interested in Ali’s work, you can keep updated by following her on Instagram @the_animalgirl.

The El Socorro Centre for Wildlife Conservation is in dire need of donations. People interested in making donations can reach the centre at its website: www.wildliferescuett.org or contact the centre’s director Ricardo Meade at 366-4369.

Comments

"Hukaymah’s haven for rescued animals"