City Twilight: Poems that pulsate with the Trini voice

Kenneth Ramchand

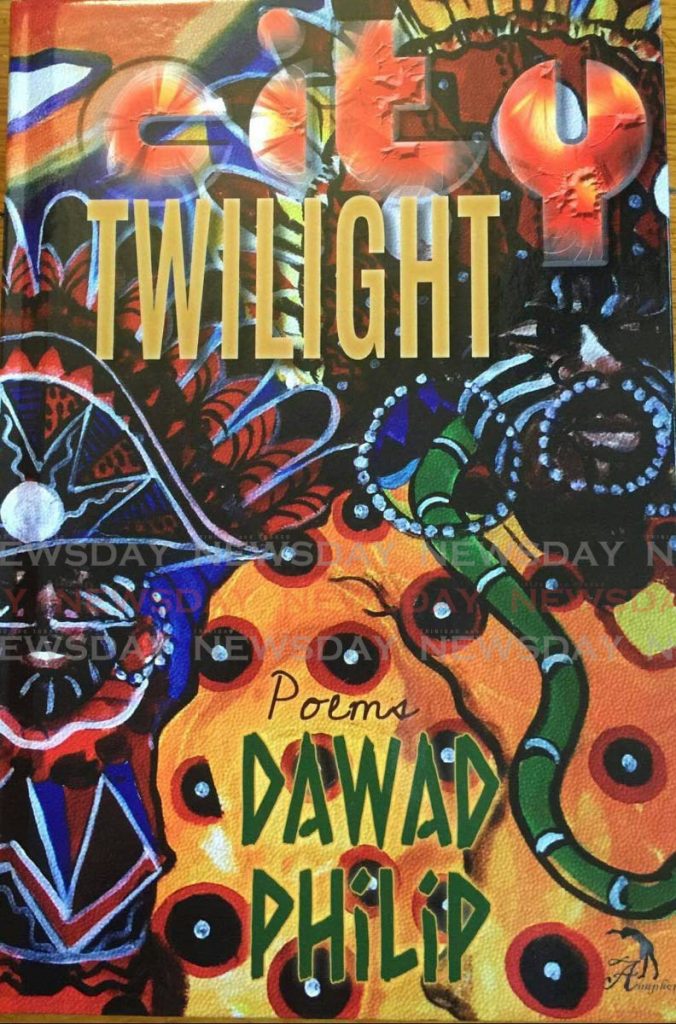

City Twilight

Poems by Dawad Philip

Jazz, blues, calypso, Carnival, dance, and the full range of the Trinidadian tone of voice are the body and soul, and the lifeblood pulsing in these well-orchestrated and careful poems. You pick up the tune at once, and the unpretentious words and phrases ease you naturally into the human substance.

These poems are all the more accessible because most of them are stories in disguise. When it is appropriate the poems boldly join the cadence of regular stanza with the rhythm of prose. The poems/stories are uttered by a sedate teller finding the right keys to respond to the anxieties of the twenty-first century and to remember simultaneously, without intrusive ego, the times, places, persons, happenings and cultural nodes that have shaped the poet’s earlier life and serve as a vaccine against the viruses of the present.

These poems are very much about a particular society and the worlds to which the poet has been exposed, but they have a subtle and important metaphysical dimension. Taken together, the poems in City Twilight hold two twilights in balance: the darkness that falls when the day is over, and the darkness that evaporates with the coming of the light at dawn (Las Lap and J’Ouvert, as it were).

They counter the social and racial tensions of harsh day with the power of pure humanity and a submarine tribal culture that is second nature. Thus: A mas man and badjohn brings a sledge down on a man’s head and disappears into London where the spirit fetches him back as bandleader, limbo dancer, calypsonian and a progenitor of the Notting Hill Carnival (City Twilight). Also: Year after year, without missing a day, a retired old man in Grey Area stands up against the shambles and the cynicism around him, taking pride in his punctuality and maintaining poise and dignity as he presents himself for work at a closed-down oil refinery. Again: In The Blue Coronet, one of the many pockets of black resistance and self-affirmation in the New York where the writer spent several years, the spirit moves in Miles Davis and Sonny Stitt:

When the bassist nudged him, Sonny Stitt

rose to his feet, lifted his horn and testified

They can’t take that away from me.

Seventeen of the thirty-seven poems are dated 2020 and the reader relives the ruination brought by the lethal diablesse (“Covid is her name and her kiss is turning lungs to glass”). The reader thrills to the drums when the poet enters the gayelle to karay all day against The Deaf Dancer, who is an incarnation of the gorgon Covid. The reader is also moved by the held-in pathos in the austere Golden Carriage as George Flood is charioted to his first and final resting–place, “Calling, Mama! Mama! Mama!” Many of the poems deal with the emotional challenges of covid19 and the tilting of a one-sided world that for too long depended on a refusal to acknowledge that Black Lives Matter.

These poems in all moods reflect Philip’s own journeys, the sustaining group life and the elixir of music among African-American souls; the disconnection and the lack of understanding experienced in Eastern Europe (see The Blond Conductor and other poems in the section of the book called The Blond Conductor). They also enact a process that motivates the poet: the reconstitution of self and culture in the fractured world to which he returned in 2002.

The society’s sad loss of vision is described in Balisier a poem of 1986; and the rot that has set in is brilliantly bulleted in the rasping lines in the middle of

Chacun pour soi, whose first two stanzas trace in melancholy tone the spread and contaminations of sheer individualism. The poet can still taste the freshness of The Hills of Paramin, relive the community feeling of Country Christmas and the binding human empathies of A Funeral before Covid19, but he is aware too of the savagery of his society that manifests in The Hunt. His return to the island has been

Il Passaggio della Morte, a passage to death.

The poems know about the violence of the gangs (Rasta City, Unruly Isis), and the alienation of the youth in Wet Man Kingdom, a society that wants to evade responsibility by guiltily denying the existence of the “children of the Barber-Greene, /who disappeared from this invisible island”. The poems know that this doom started a long time ago: ‘Then I heard a youth say,/ This ain’t about Unruly and Rasta, Daddy,/this brew ain’t now start, so this long overdue.”

Philip’s sure regulation of the cadence, his instinctive discovery of the right register of the Trinidad language, his building of the new ships are intimated again and again not only in his meticulous attention to craft but also in his submission to the healing process in which the poet is involved. The image in Red Moon of the poet bleeding poems and delivering sons of light is one intimation of the process. But the poem that seems to root the life and work of the poet in an endless encounter with the gorgons from age to age is the beautiful and beautifully modulated Zangi Olga, that begins thus:

There is a man learning

to walk again, like a child,

down in Bhagan Trace,

in Chandenagore,

in Chase Village.

There is a man lost in non-existence,

a moringa tree against a leaning

fence, the abandoned canefield

his landmark. The kennels still

there long after the dogs have died.

There is a man seeking to fashion

a new identity from dust, needing

to validate the memory of things

If you want to be persuaded to read every poem in this collection, if you want to see the world in which you live as it is and as it was, and if you want to listen to the still sad music of your humanity and native being, begin with

Chacun pour soi and Zangi Olga.

City Twilight will be launched on Sunday via Zoom at 4 pm.

Comments

"City Twilight: Poems that pulsate with the Trini voice"