Chevening Scholar Thompson wants justice on time

THE wheels of justice turn slowly in TT and 2020 Chevening Scholarship winner Danielle Thompson wants to reform the criminal justice system to change that.

Thompson, 36, is a state counsel three in the Office of Director of Public Prosecutions. In the nine years she's worked there, she’s seen children on trial for murder, career criminals with a revolving door in the courts and victims re-traumatised on witness stands.

“Our system is overburdened. The wheels turn slowly. If you were to compare our system with the US, they don’t go to trial with the percentage of matters (that) TT does. Matters would turn over faster in the States.

"Right now, we are prosecuting cases that happened in 2009-2010, some older, some newer. It’s a slow process,” Thompson told Newsday.

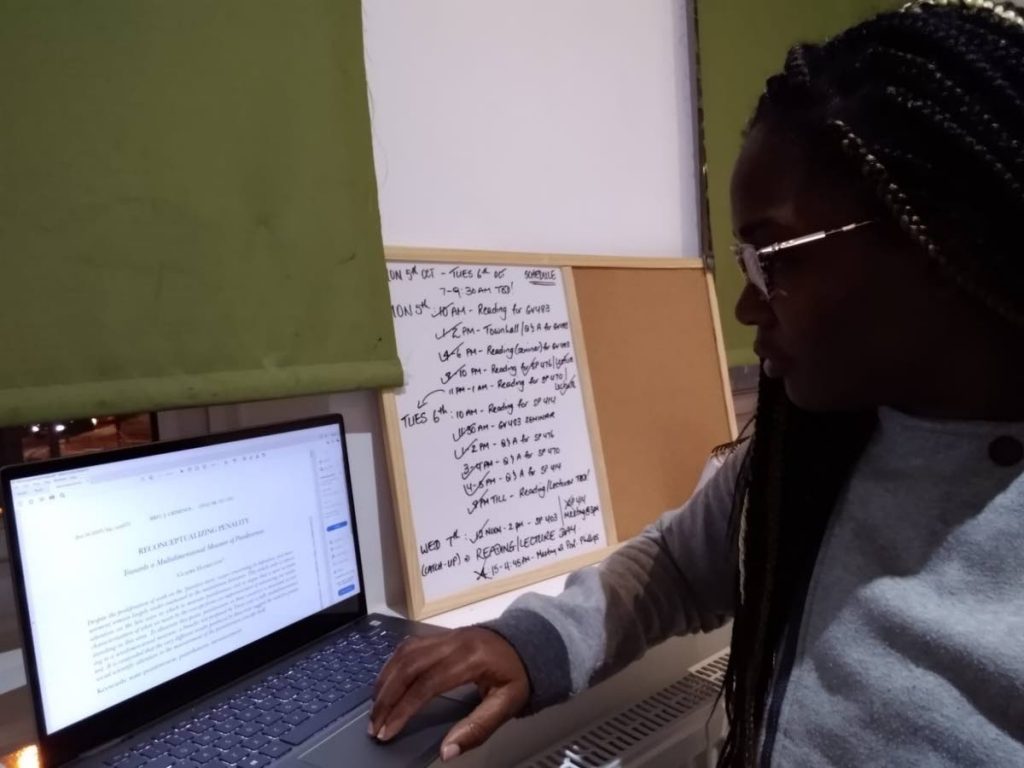

Thompson is in England on study leave, reading for a master’s degree in criminal justice policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her programme of study looks at the different aspects of the justice system and how the police, judiciary and different agencies involved work together. From a policy perspective, her classes will look at the infrastructural policies and trends of countries with swift-moving justice systems. She also gets to sit in on lectures on criminology and criminal justice.

“This is a great opportunity for me to pick the minds of people who are actively involved in law. We are still heavily UK-based in our laws: the highest court of appeal is the Privy Council.”

She plans to return to the Office of the DPP with fresh ideas to fix the criminal justice system.

“My hope is to eventually be in a place where I can represent, not just the interest of the DPP’s office, but be one of the voices developing policy…I want to influence the formation of a committee to deal with criminal justice reform.”

On her return from the UK, she’ll still be a prosecutor, but she wants to have stakeholder meetings that treat the justice system as a whole. She wants a standing committee of all stakeholders, from forensic science to the police, so the different cogs of justice do not work independently of each other.

Thompson is thankful for all the support from her colleagues.

“I’m grateful for the community I was able to build at the DPP’s office. The support really helped, especially as a single parent, for all the stresses of the job–because we really are overworked. A lot of the people here are good people.”

In 2014 Nigel Sandy, Jameel Earle, his mother Denise Earle and Anton Boney were charged under the Anti-Gang Act. Boney faced five charges, one of which was being a gang leader. This was one of Thompson's first big cases and it involved over 80 witness testimonies. It was not her first court case, but the beginning of her prosecuting cases on that scale.

She said she went up against attorneys with more experience than she had, and the experience boosted her confidence in her skills and taught her about respect for all people.

“Regardless of who you are dealing with, and what your job may entail, always treat people with a certain level of respect – not that I didn’t already know that – but it brought that lesson (home to) me in a real way.

“It is easy in our culture to disregard people. It is important, regardless of who – once you are dealing with people, treat them in a fair and upstanding way. People respect you even more.”

She said she applies this respect to witnesses and accused people, so she maintains her integrity.

“Even when they are sent to jail, they see me as someone who is just doing a job, as opposed to someone who is trying to persecute them. It is important in my job that I am always seen as a prosecutor and not a persecutor.”

Her goal is not just to be a lawyer but to help with the administrative management of the legal system.

“I genuinely believe that a system that works better will also help curb and reduce crime.”

She believes there are different factors contributing to the overload of the criminal justice system that are outside the judiciary’s control.

“We have to look at it on a broader scale, because having more judges by itself won’t help. More courts by itself won’t help.”

The Forensic Science Centre’s capacity to process evidence from multiple cases and the St Ann’s Psychiatric Hospital’s ability to assess people’s mental state to stand trial are contributing factors.

“You could have all the judges in the world, but if those different agencies are short-staffed and things take years, which they do, then it’s only so fast you can go, because the interest of justice does not dictate speed.” She said when people think about a prolonged court case, an accused person languishing in remand yard for years comes to mind.

But consideration must also be given to the feelings of the victims.

“A lot of people forget the victims. We’re talking about somebody who lost a family member or somebody who’s been sexually assaulted, chopped or mugged who has this trauma and no closure…I see it. I deal with the people, families and victims, who, after years, say: ‘I don’t want to have anything to do with this, I’ve moved on with my life and you’re bringing back trauma.’

“What’s the alternative? To let potentially guilty people walk free? We also don’t want that.”

A delay in cases, she said, also affects the police’s ability to accurately present evidence. In some cases, police officers are expected to go to court ten years after they have charged someone to present detailed evidence, but the ability to accurately recall an event diminishes over time.

“Can you remember exactly what you were doing ten years ago in your job? Whatever notes you may have made, you may be able to refresh your memory, the nitty-gritties–who remembers that?"

The pain of waiting so long for a criminal case to be closed compelled her to look for solutions.

“I have seen people sitting down in my office in tears. I have seen family members of accused people when their loved ones are coming out of jail and they are bawling down the place because they haven’t seen them outside in years.”

She also believes a swift justice system is a good deterrent.

“If I see my partner get charged and a day or two later I see he gets locked up for 20 years, I might think twice about going down that path. But if I see he gets locked up and he gets bail and ten years later, he’s still living his life, by design, when it reaches around to trial, no one even remembers half the time. The matter is no longer in the public domain. I genuinely think if our system is working better, it will have a trickle-down effect on the condition of crime on the first place.”

The issue of repeat offenders, she said, is also quite worrisome.

“We have a high rate of career criminals…We really need to start looking at it at a deeper level than just solving crime. Just solving the crime means people will be repeat offenders.”

She believes social assistance programmes that help support single mothers, mentor students and give support to those in need will help reduce the country’s recidivism rate.

Thompson attended St Joseph's Convent, St Joseph and knew university was her next step after secondary school. It was only when she started working at the DPP’s office that she realised not everyone shared the same type of life and mentality.

“A lot of families are struggling...I may have been able to go to school without having to worry about working and bringing in an extra income, but not everyone is that lucky.”

She’s told many people she meets in court that if they go to school, their odds of getting a higher-paying job will increase.

Middle-class people, she said, do not usually have the same problems as people who resort to crime.

“They don’t know the struggle…People think they have an option outside of committing crime...Because we don’t have a probation system, even things like looking for a job are a challenge…All of these are factors at play in whether or not a person commits another crime.”

Comments

"Chevening Scholar Thompson wants justice on time"