Let’s keep washing hands

EVERY TIME I go somewhere and see a sink for customers to wash their hands before entering a business place, I think of the day my friend Onie lost her job. Fifty-one years ago, Onie and I worked in a Howard Johnsons cafeteria in Ohio. We wore hairnets and followed strict hygiene procedures. We had been warned about “spotters,” HJ employees who visited the company’s restaurants acting like ordinary customers so they could bust waitresses for unhygienic practices.

On that day, a spotter demanded that Onie, who was working behind the counter, take his money. This was strictly forbidden, but the spotter proved persistent. We had been warned that we would never be able to spot the spotters, and that we should never take money if we were handling food. We were told not to touch our faces, hair, uniforms or the counter, and if we did, we had to wash our hands immediately because spotters seeing these violations could have us fired.

So the spotter demanded Onie take his money and then sent her back to get a Coca-Cola after she touched the money. He then walked to the back door and demanded her job. Our boss, Judy, begged for Onie.

This all seemed unfortunate, but not drastic to me because we had been warned. Besides, my mother was a cleanliness freak. After a stint in a tuberculosis hospital before I was born, she returned home as a handwashing fanatic.

Imagine my surprise when I discovered a world that didn’t follow the strict handwashing policies of Howard Johnsons or my mother. I can’t tell you how much abuse I suffered over the years from asking restaurant workers to please wash their hands when I observed they had touched their hair or face while serving customers.

Long before covid19 I asked myself how did we get to this point where the Ministry of Health has to tell us to wash our hands regularly and not touch our faces? These covid19 prevention measures would have served us well every flu season.

The good news is when it comes to cleanliness we're doing much better than I had ever thought. Cleanliness is really a relatively new concept.

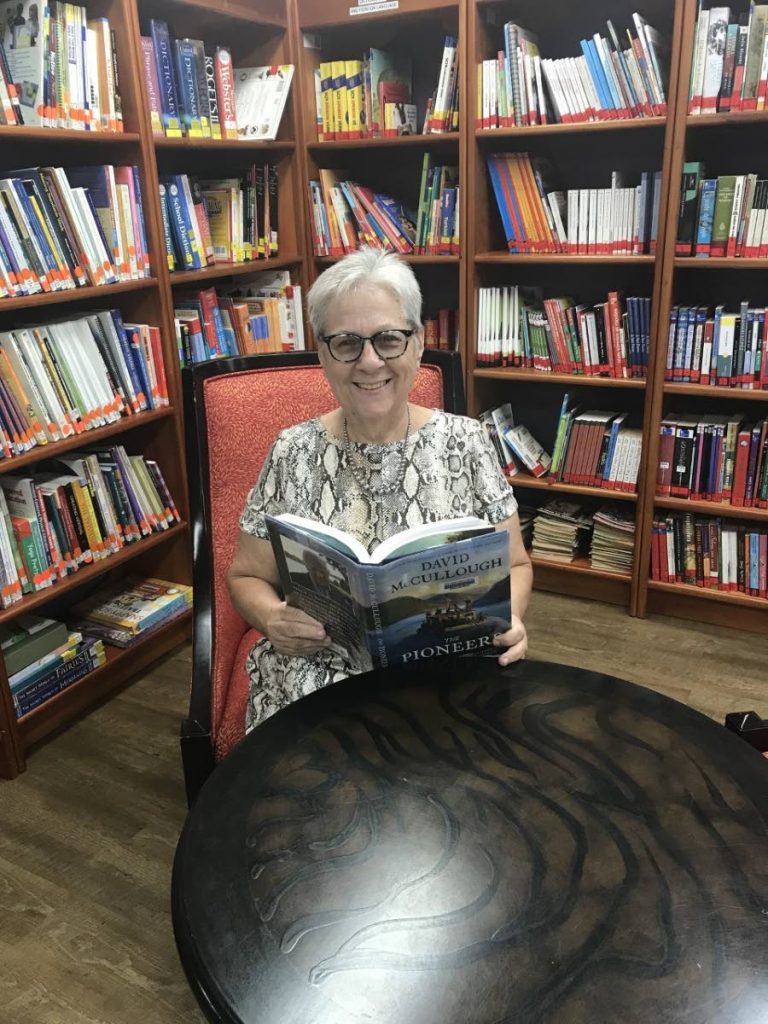

I learned this last week, when I read David M Oshinsky’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book Polio: An American Story. The non-fiction book about the race for a polio vaccine reads like a Dean Koontz horror novel. It gives a clear picture of the challenges of creating a vaccine, but that’s another story.

In his book, Oshinsky says that Americans and cleanliness weren’t compatible concepts before the 20th century.

Oshinsky writes: “In 1900 toothbrushes were still rare in the United States, deodorants and shampoos almost unheard of. Few people bathed more than once a week or rinsed their hair more than once a month. Fewer still washed their hands before eating or after using a toilet. Spitting was almost universal. Travelers shared beds and chamber pots with complete strangers…Cities reeked from the stench of garbage, horse droppings, slaughterhouses, tanneries and open sewers.”

He didn’t mention urinating on the streets, but we know that was a common practice as well.

He says our idea of cleanliness changed after scientists linked unknown “agents” to diseases like typhoid, cholera, tuberculosis and gonorrhea.

An emerging germ theory caused men to shave their beards and women to shorten their skirts so they no longer swept the ground when they walked. Hotels began to issue bars of soap in the early 1900s. Cellophane became an important invention. Now we are lamenting the overuse of plastic in supermarkets, but in the 20th century it was synonymous with hygiene.

By the 1920s, Lambert Pharmaceutical Company in St Louis began marketing Listerine mouthwash, named after Joseph Lister, who became famous for sanitising operating theatres, which was a revelation to surgeons in 1877.

By the 1930s, soap, “a product of limited appeal only two decades before,” now ranked third (just behind bread and butter, but ahead of coffee and sugar) on the list of the so-called essentials of life,” writes Oshinsky.

The point is that the merits of good hygiene took a long time to sink in. Even today it’s difficult for us to be ever-vigilant with deadly enemies like viruses that we can’t see. It was difficult for us to grasp the concept a century ago, and it’s not much easier to grasp the concept today.

I hope that we keep the practice of washing hands before we go into business places. A few months ago it seemed strange and new. Now it all seems like common sense.

Comments

"Let’s keep washing hands"