My father the insurgent: Jamaat member’s son on life, legacy after 1990

Muhammad Muwakil’s two clearest childhood memories of his father are of the time he explained the dangers of playing outside; and the time his father tried to overthrow the Government.

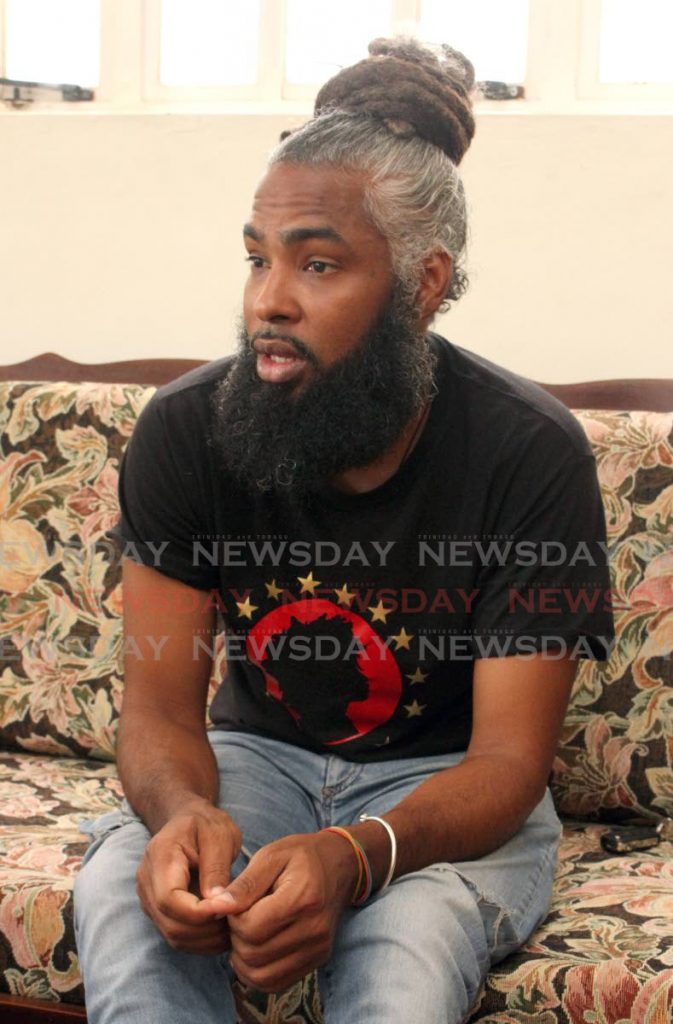

Muwakil, 36, a musician, is a founding member of the socially-conscious musical project Freetown Collective.

He spent the first six years of his life at the Jamaat al Muslimeen’s Mucurapo compound.

It was there he learned the dangerous realities of life from his father, former insurgent and head of the Jamaat’s security detail Salim Muwakil.

The 2013 report of the Commission of Inquiry into the 1990 attempted coup describes Salim Muwakil as being “actively involved” in a plot to assassinate prime minister ANR Robinson, and identifies him as one of the Muslimeen responsible for organising explosives to destroy the old police headquarters on St Vincent Street, Port of Spain.

Muwakil recalled, “My father used to warn me about playing outside after dark, but I didn’t listen to him until one night he came and showed me two things in his hands.

“One was a bullet and the other was a flat metallic disc.

“He said the disc was what a bullet looked like when it hit a wall – and then asked me if I was as hard as a wall.

“This was his way of teaching me about the realities of the outside world.”

Another early memory of his father is of hearing about the “drug raids” members of the Jamaat would go on: they would intimidate and often beat drug dealers before taking their cash.

Now Muwakil acknowledges that his father’s lifestyle was not an ordinary one, but in those days: “My dad was like everyone else’s dad who I knew. I didn’t have a normal life, whatever that means, in terms of that interaction.

“Police were kicking down our doors without knocking…and pulling people out at least once a week.

“A lot of things were going on which to me, looking back on it, as a child was like a warzone, really. Police would pass and shoot at the mosque; we would go under the desk and come back up afterwards.”

On July 26, 1990, Muwakil, his mother and his two sisters left the Mucurapo compound to stay with his paternal grandmother at the house where he gave this interview.

On July 27, his father, led by Imam Yasin Abu Bakr and 70 other insurgents stormed TTT studios on Maraval road.

Muwakil’s earliest memories are of looking at television in the living room and seeing a man he would later recognise as Abu Bakr, announcing something that he, at six, didn’t understand.

“We started laughing, because we thought it was a game, but then my mother who was also watching the television at the time, told us to quiet down and she began listening to what was being said.”

From their Belmont home, Muwakil could see smoke from fires in uptown Port of Spain, and hear the gunfire.

He still did not know what was going, but one memory stands out.

“There was an explosion at TTT studios and my mom went and put out my dad’s funeral shroud on the clothesline.”

From this Muhammad realised that even though his mother may not have known exactly what was going to happen, she anticipated the worst.

“And again, at that age I didn’t understand what was going on fully, but there was this air of suspense and danger around.”

Muwakil says the topic of death was never taboo in his family, but was welcomed and acknowledged as a natural part of human existence, something his father had instilled in him since early childhood.

“We kind of grew up with this sense that death wasn’t something to be feared, and although you understand the seriousness now, especially for someone that was close to you, it still was almost like this is part of life and our parents never encouraged us to be fearful of death.”

But in the days that followed, the family ate, slept and watched television on edge, careful not to draw attention to themselves, as the authorities were on the prowl for the families of insurrectionists.

That was when Muwakil began sleeping with a knife under his pillow, a habit he now attributes to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) caused by the insurrection.

“I think as a child I went inside at that point. I became very introspective and quiet, because I started to think about what my position was, what was my role now for my mother and two sisters, me being the only boy for three generations in this family.”

One bizarre memory is: “My dad and they did call here from TTT to see what we wanted to see on TV, so people who saw all those cartoons for the six days – that was us.

“He called here a few times. I don’t remember talking to him, but I probably did.”

After that all he remembers of the days of the coup attempt is the final moments as the insurgents who emerged from TTT were rounded up into buses.

Knowing that the police would ramp up their searches for the coup-makers’ families now that the crisis was over, Muwakil’s mother packed up her children and moved to a more isolated area in Maracas, St Joseph.

The sudden move, together with the unusual seating arrangements for the drive, showed him things would never be the same for his family.

“I remember my mother didn’t wear her hijab, and she was down in the space between the back and front seats of the car we were travelling in, to avoid being seen.

“These were things that brought home how serious the situation was for me as a child, because before that moment I never saw my mother without her hijab.”

In the months that followed the family lived by their wits.

“When we left here and we were alone, there were a network of the wives of the insurgents, and my mom would reach out to people.

“I remember very distinctly going to a lot of the markets and stuff, and anything the vendors would deem not fit for sale, we would take it and put it in boxes and go through them and throw away what really couldn’t be used, while salvaging what could be used.”

Muwakil, his mother and sister visited his father, who was detained at the Teteron Barracks, Chaguaramas but were not allowed to speak to him in person.

Muwakil said their only form of communication was through small rolled-up notes thrown out of the van that transported the prisoners, as they drove past their relatives.

When he was reintroduced to the man he had heard so much about, but could scarcely remember, it was a bittersweet reunion, as he and Muwakil, then only ten, had to pick up their relationship where they left off.

“We went to the mosque and there was a lot of jubilation after the men were returned. “The energy of having a man in the house was a different vibe. In my mind, I was running things in the house – and then there’s this man who comes and basically takes over.

“I was like, ‘I don’t know you,’ so for a while I wasn’t really at ease. I (didn’t) know if he came to stay or what exactly his role was in the house, if they would carry him back to jail or what.”

But now, he says, he and his father have a mutual trust and respect, with their common ground being the younger Muwakil’s own work as an activist.

“Only of late he would call and check up on me. He would always try to prepare us for life without him. It was never a Sunday morning chit-chat, ‘How was school?’-type talk. I think it’s because he was a man who has always lived on that edge.

“I think he’s proud of me. I think he’s also proud that I’ve taken a different method. I don’t have any gun, but I know he’s proud of me. He advises me on certain things, but he gives me my space to make my own mistakes and errors.”

Only a few people know about his father’s involvement in the coup attempt. Muwakil is not ashamed of his family and does not shy away from it.

“It’s not something I go around advertising. I didn’t see it as some badge of honour – nor was it a badge of dishonour,

“I just wanted to make my way in the world. I knew if people knew that about me beforehand, they would make their assumptions and I might not have had the chance to be the human being I wanted to be.”

Being known as the son of an insurgent has had its challenges. It has cost him relationships and led to his being singled out by police.

“There would have been women in my life that I wanted to be with who distanced themselves after learning about that.

“My first girlfriend, her father was a hostage in TTT, and when her parents found out about that, they didn’t want her anywhere near me.

“Sometimes police officers have issues when they stop you and find out what your last name is. That has happened a good few times over the years.”

Today Muwakil’s thoughts on the attempted coup and its impact are conflicted.

Once an ardent believer in the ideology behind the insurrection, he explains that eventually he realised no amount of reasoning could justify the loss of innocent lives.

“I was about ten or 11 years old and I read a book on the attempted coup that was written by one of my father’s friends, and that’s when I realised that when they blew up the police station, people died, and when they went into the Red House, the security guard was killed.

“It was then I realised that this wasn’t a bloodless coup. When the army was shooting at the building, people were killed.”

According to the commission of inquiry’s report, a total of 24 people were killed during the fighting between the Jamaat and government forces including Diego Martin MP Leo Des Vignes.

“I always thought that what happened was completely justified and people shouldn’t have any other views of it. I felt that way because of how I grew up and seeing what the police were doing and how I was told our society was operating. (But) when I realised people’s mothers, fathers, grandfather and uncles died, it took another kind of turn for me.”

He also recognises that what began with a single objective – to end what they saw as harassment at their compound – led to different Muslimeen members having their own agendas and aspirations.

He maintains that a sense of helplessness and frustration among the Jamaat and the wider public were what led to such a response.

He also believes as society attempts to dissect the insurrection, we may be asking the wrong questions.

“What redress is there for the common person, for the average man who has no political links or otherwise when the law itself is against what is right? “That’s what we have to ask ourselves.”

Comments

"My father the insurgent: Jamaat member’s son on life, legacy after 1990"